Baisakhi, in mid-April every year, witnesses peak arrival of wheat and its procurement in markets of Punjab and Haryana. This year, only 31.5 lakh tonnes of wheat was procured by 14 April 2023. So it is quite an achievement of the state agencies of Punjab, Haryana and Madhya Pradesh that all India procurement has reached 261 lakh tonnes by 18 May, 2023. Yet the government may have to allow zero duty import of wheat.

The quantity procured so far should be enough to meet the requirement of wheat for Public Distribution System under National Food Security Act 2013 (NFSA), now renamed as Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana (PMGKAY). But it is much less than the estimate of procurement, which was 341.5 lakh tonnes.

Lower procurement forecloses any opportunity before the government to make any additional allocations in the run up to General elections in April-May 2024. Incidentally, the additional allocation of 5 kg per person of food grains per month, given free of cost, was offered as one of the key reasons of victory for the BJP in the assembly elections in Uttar Pradesh in March 2022.

Also read: Centre’s Ordinance not what Kejriwal wants. But Modi govt is acting well within its rights

What estimates tell

Due to rather excessive temperature in February and untimely rains in March and early April 2023, it was feared that the wheat production would be lower than the second estimate of production (released on 14 February 2023) of 112.18 lakh tonnes. The trade estimate of production is less than this. Since there is a ban on export of wheat, the private trade would not have made any purchases for export. It is also possible that the farmers of Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh may have retained wheat in expectation of higher prices.

Lower procurement, is therefore a proof that the government estimate of production may be on the higher side.

This is the second year in succession that the wheat production is lower than the government’s estimate. Last year, the initial estimate of production was 111.32 million tonnes, which was later revised to 107.74 million tonnes. Domestic consumption of wheat is estimated to be about 97 million tonnes in 2021-22. So, any serious shortfall in production is likely to result in inflationary pressure on wheat. That explains the double-digit inflation of wheat in 2022-23. As late as January 2023, the wholesale wheat prices were touching Rs 3,000 per quintal in Delhi and MP. It was due to aggressive sale of wheat in the open market under the open market sale scheme (OMSS) that the market prices in major wheat growing states came down by the end of March to almost the level of MSP of Rs 2125 per quintal.

Also read: Modi govt’s GNCTD ordinance proof BJP still clueless on Delhi’s politics, AAP

Allocation constraints

The normal allocation of wheat under PDS is about 240 lakh tonnes. In 2022-23, the allocation was reduced due to lower procurement and instead of wheat, rice was allocated to the states. The ration card holders are still receiving more rice than wheat even in predominantly wheat consuming states.

In addition to PDS, the government allocates about 11 lakh tonnes of wheat under Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and about 5 lakh tonnes under Pradhan Mantri Poshan Shakti Nirman (PM-POSHAN), earlier known as mid-day meal scheme. About 7 lakh tonnes of wheat is allocated to the states, which had issued more ration cards than the persons projected to be eligible by Niti Ayog for subsidised food grains under the National Food Security Act 2013. This is called NFSA tide over.

Thus, the total requirement of wheat is at least 263 lakh tonnes. It means that if the normal allocation of wheat is restored, the government will not have much scope for allocating wheat under the OMSS, which has been used by successive governments as an effective tool to cool down wheat inflation.

Allocation of some quantity of wheat under OMSS will be possible only if allocation of rice instead of wheat continues in 2023-24 also.

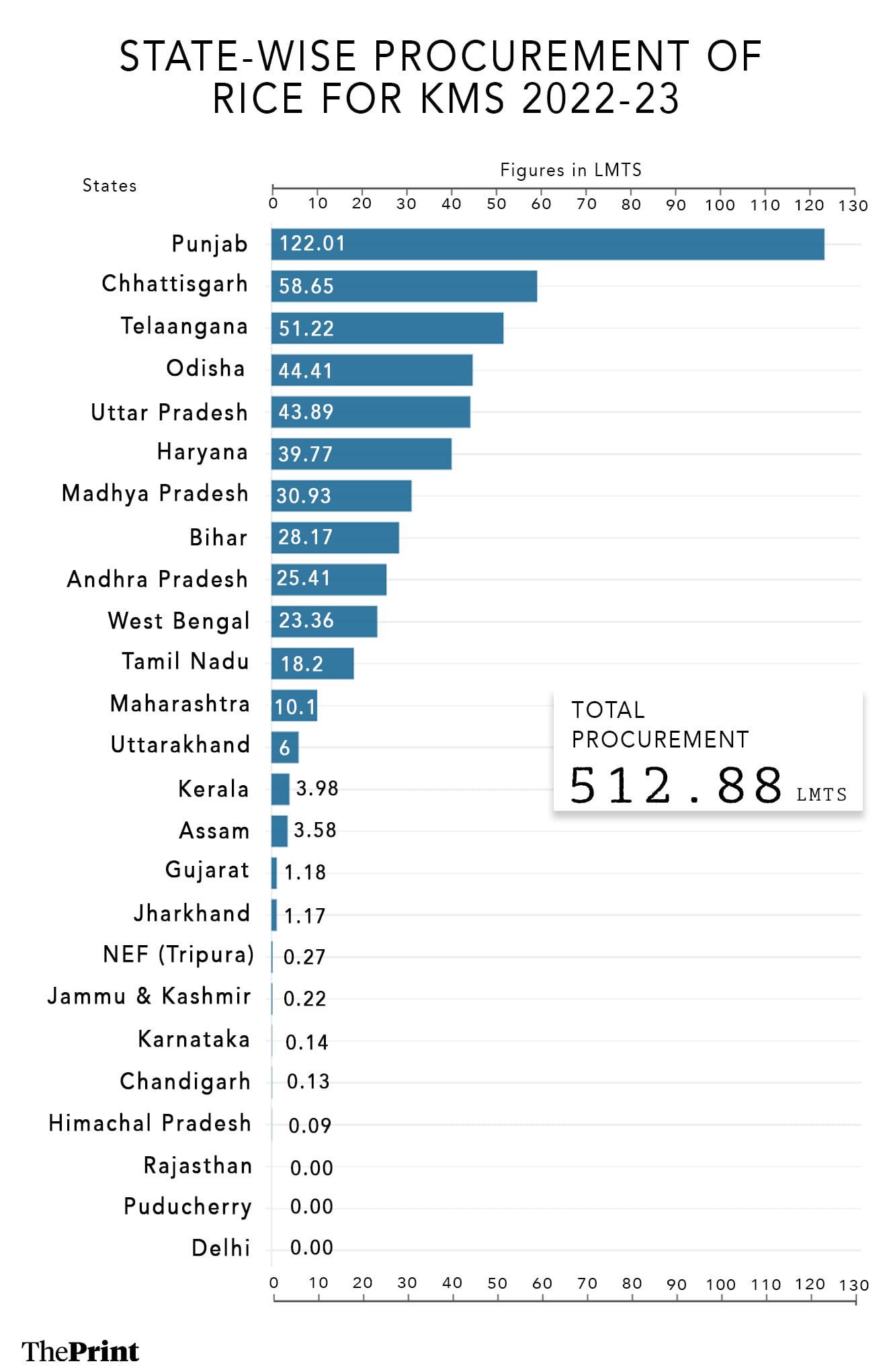

Wheat prices are generally the lowest at the time of peak arrivals in April and May. But this year, wheat inflation in April was 15.5 per cent. Despite a shortfall of rains last year in UP and Bihar among other states and lower production of rice, the government has procured 512.8 lakh tonnes of rice, which is creditable. But the non-PDS rice inflation in April 2023 was 11.4 per cent.

Also read: Pakistan’s oil deal with Russia shows it’s getting best of ‘both worlds’. India must take note

Added uncertainty

As we move into the monsoon period, there is an added uncertainty about the impact of El-Nino on kharif crops, especially rice. Therefore, the government would be quite concerned about food inflation.

If the Government continues with the reduced allocation of wheat, it may have 2 to 3 million tonnes to offer under OMSS.

Depending on the behavior of el-Nino and its impact on monsoon, the management of food inflation will demand proactive policies.

At present, the duty on import of wheat is 40 per cent. It is possible that going forward, the government may allow duty free import of wheat. If global prices remain up to $280 per tonne, it may be viable for flour mills of coastal states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Andhra Pradesh to import wheat from October 2023 onwards. However, the import of wheat in Karnataka ports may still not be viable as the freight from Mangalore to Bangalore is Rs 1,500 per tonnes.

Two successive weather events have affected India’s wheat surpluses and taken it off the global export market.

Saini is an Agricultural Economist and Hussain is Former Secretary, GOI. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)