Even five decades later, Satyakam is a reminder that moral beliefs, practised and not just spoken, come at incredible personal costs.

In the age of easy internet activism, with daily hashtags revolutionising social media platforms where people claim to stand up for justice and fairness in the name of being ‘woke’, Satyakam is an essential, but an uneasy parable.

Made by Hrishikesh Mukherjee, one of India’s most-loved directors, and released in 1969— the year Congress party split into two— India that year was close to insolvency and Indira Gandhi had nationalised the banks. Satyakam captured the continual decay in the Nehruvian dream of a meritocratic, just society in the dimming afterglow of Independence.

The bleak film failed in its time because Bollywood romance ruled that year. But Satyakam has gained prominence since.

As internet activists trend hashtags asking citizens to talk to fellow countrymen and technology companies get blamed for fake news, Satyakam demonstrates what fake looks like. It is an unflinching, forensic scrutiny of what ‘truth’ is — and a timely reminder for us in this era of post-truth, alt-truth and ‘incorruptible’ leaders.

Based on Narayan Sanyal’s novel of the same name, the unconventional drama is perhaps the most difficult viewing from a director who is known for ‘middle of the road’ films.

“Main insaan hoon, Bhagwan ki sabse badi srishti

Main uska pratinidhi hoon, Kisi anyaya ke saath sulah nahi karunga

(I am human, God’s greatest creation.

I am His representative, won’t compromise with injustice.)”

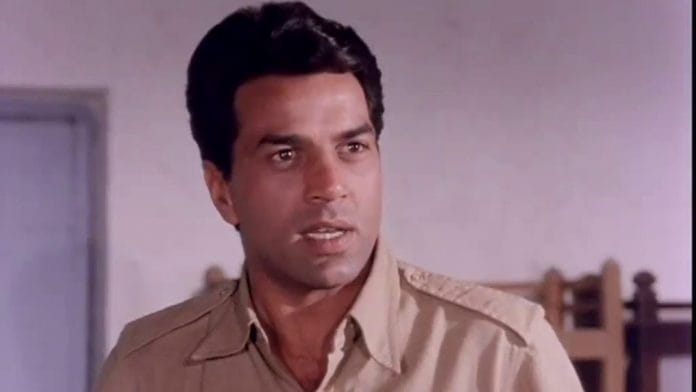

This central belief of Satyapriya Acharya (Dharmendra), the lead protagonist, forms the guiding philosophy of the film.

Satyapriya, a fresh engineering graduate in 1946, believed in the promise of hopeful times after Independence, like many of his peers and especially friend Naren (Sanjeev Kumar; a stand-in for author Sanyal). However, his idealistic certainty and staunch conviction in the idea of truth, as his name suggests, made him a different beast than all others.

As the years passed, Satyapriya had to contend with situations he never imagined. But his moral absolutism tested not just him, but those around him too, and most certainly, those on the other side of the cinema screen.

Employed in a princely state, he formed a bond with a dancing woman. But owing to his upper caste gurukul education, he did not commit to her. Once Ranjana (Sharmila Tagore), the woman, gets raped by the ruler of the state, he had to confront that hesitation. First, he tried to salvage her position by promising to get her married to a liberal person. When she denied him the right to do that, his hesitation vanished. Propriety, in his beliefs, was more important than the self. He then married her and even brought up her child. He was doing the right thing. But despite his marriage to a woman he loved, he could never bring himself to be intimate with her.

In this textured take on the idea of compromise and idealism, Mukherjee ensured that his protagonist’s arrogance in principles doesn’t go unchallenged.

Over the next few years of his life, Satyapriya had to constantly be on the move, forcing his family to suffer with him too. Towards the end, on his deathbed, he finally gave up on his morality and ‘compromised’, but his wife with whom he shared an incomplete but fulfilling relationship, didn’t let him down.

Satyapriya had to die because he never compromised in a world where living itself is compromise.

Despite his death, the film finds its light in its final scene when Satyasharan Acharya (Ashok Kumar), the self-righteous grandfather of Satyapriya who once turned him and his wife away, is stunned into silence by the naked truth from the mouth of his young grandson, Kabul (child artiste Sarika). He realises his grave error in denying his daughter-in-law her rightful place.

“Satya bolne ka ahankar nahi, satya bolne ka saahas chahiye

Chahe wo sach kitna bhi apriya, kitna bhi kathor kyun na ho.

(To speak the truth, you need courage, not arrogance

Even if that truth is disagreeable, or cruel.)”

Penned by the great progressive Urdu writer Rajinder Singh Bedi, these lines form the crux of Mukherjee’s personal favourite of his works.

In his wonderful biography of Mukherjee, film writer Jai Arjun Singh wrote, “In his attention to detail in these scenes (referring to the hospital scene)—and in other less flamboyant, but equally elegant shots—you see how personal a project this film must have been for Hrishi-da, and how invested he was in it.”

So personal the project was for even Dharmendra, who gave his finest performance here, that the film was produced by his brother-in-law Sher Singh Jung Punchhe. In a 2012 interview, the actor called the film even more relevant than before.

“I can still not see Satyakam without it wrenching me and turning my stomach inside out. It is so disturbing and cuts so close to the bone—even today, how many people would make such a film, and would they be able to release it without interference?” Farooque Sheikh, the late actor, told Singh.

In the morally difficult world we inhabit today, the display of virtue has gained more significance than actually being virtuous. And it is this humane dichotomy, of fractured relationships and uncomfortable truths, which Mukherjee captured with his emotional realism.

Even five decades later, Satyakam is a reminder that moral beliefs, practiced and not just spoken, come at incredible personal costs. And not everyone has the courage and latitude to pay them.

Very well said Deep Ji, however survival without morals or virtues as you call it will be rendered useless, eventually.

It was one of my favorite movie till i started studying everything scholarly {Critical theories, human society’s evolution, inequality, monetary distribution & policies, statistics & their manipulation techniques like P-hacking & such etc.} & the only truth which emerged from all that is that all virtues are useless, survival is the primordial factor we even try.

I still like the movie but i don’t adore it now as i used to.

An extraordinary movie indeed. Poignant yet a smudgeless mirror that only a shameless will look into and be able to offer a cynical smile. Very relevant indeed for anyone that’s part of the rotten system but still has the capacity to reflect.

Dharmendra was honoured with a Filmfare Lifetime Achievement Award in 1997. He became emotional, saying that he had never won a Best Actor award all these years, despite having been successful and acting in over a hundred popular films. If I am not mistaken, he mentioned Satyakam as a film where he felt he had deserved that honour.