The year was 1929. The royal Darbar of the Nizam of Hyderabad Mir Osman Ali Khan Siddiqi, Asaf Jah VII glittered with the best of musicians from across the country. In deference to the Nizam, many of the singers performed standing in front of him. But there was one singer who made the Nizam sit up and take note of the wonderful voice he was listening to, and forced him to accord due respect of allowing the performer to sit down and finish the song. That talented singer was Bai Sundarabai Jadhav from Pune, who, though forgotten now, was one of India’s most celebrated recording artists of her time and whose repertoire spanned several decades and became popular through different forms of media. So pleased was the Nizam with Bai Sundarabai’s Urdu diction and rendition of ghazals that he also permitted her to sing his compositions.

Sundarabai was born in 1885 to Marotrao, a contractor, who had noticed the innate musical talents in his daughter quite early. The father took Sundarabai, who did not attain any formal education, to Satara, where she trained initially in light classical music. It was here that Sundarabai added a vast corpus of Marathi folk songs (known as Lavni) to her musical talent from her guru Dabhade Gondhali. In Pune, Sundarabai learnt Hindustani classical music under Shankarrao Ghorpadkar. She also found an unusual teacher in mystical Thakurdasoba, who enriched her repertoire with several devotional songs and bhajans.

Such was the dedication of Sundarabai and her father that when Thakurdasoba suddenly decided to migrate to Bombay, Marotrao, who wasn’t quite well-off, decided to rent a small room in the city’s Chirabazar near Girgaon – close to a temple where Thakurdasoba had decided to spend his life. In the precincts of Gora Ram temple of Thakurdwar, Sundarabai’s voice blossomed to greater heights with several soulful bhajans that she later popularised. Polishing her Hindi and Urdu diction, she also learnt ghazals, Hindustani music, as well as the folk songs of the Banaras region under several gurus like Dhamman Khan, Gulam Rasool Khan and Keshav Bhaiyya.

Also read: Coimbatore Thayi, the Carnatic singer who struck a chord in Paris but is unknown in India

With this kind of eclectic training, it was just a matter of time before Sundarabai took to live performances. She received wide acclaim from connoisseurs within and outside Maharashtra. Her guru, Dhamman Khan, was a tabla maestro and often accompanied her to her classical concerts. During her many concert tours, Sundarabai came in touch with the musical divas of her time – Vidyadhari Bai, Siddheshwari Devi and Rasoolan Bai (all from Banaras) – and incorporated the purabi style of singing from them into her own. From Lucknow to Banaras to Hyderabad, Sundarabai was a rage across India.

Quite expectedly, her music soon caught the attention of veteran Marathi theatre thespian Bal Gandharva. He was conceptualising a play, ‘Ekaach Pyala’, in 1920, and asked her to compose the music for it. Sundarabai readily agreed and the outcome was a series of hit Marathi natyasangeet songs as well as ghazals that were used in the play.

In October 1921, The Gramophone Company and its recording agent George Walter Dillnutt solicited Sundarabai for recording sessions. Ever the innovator, she agreed to this offer as well. In Bombay, she cut about 12 records under the Zonophone label for them in this session. Among them is the following Thumri in Raga Piloo, ‘Chhodo Mori Baiyyan’.

There was no looking back after this for Sundarabai. With the entry of electric recording in 1925, artists could sing without the limitations that they faced during the acoustic era, including having to scream at high pitch. Sundarabai recorded for numerous labels such as Odeon, Regal, Young India, The Twin, and Columbia. In a recording career that spanned for 30 years, Sundarabai cut close to 100 records, recording about 180 songs on them.

Also read: Janki Bai, singer disfigured by 56 stab wounds sold more records than her contemporaries

The influence of the north Indian musicians, especially from Banaras, is clearly reflected in the following recordings: a Dhun in Raag Yaman: ‘Kunjanban Mein Sakhi’ and a Hori (sung during the festival Holi): ‘Tum to Karat Barjooree’. These were recorded for the German Odeon Company in Bombay in 1934.

Kunjan banmein

Tum toh

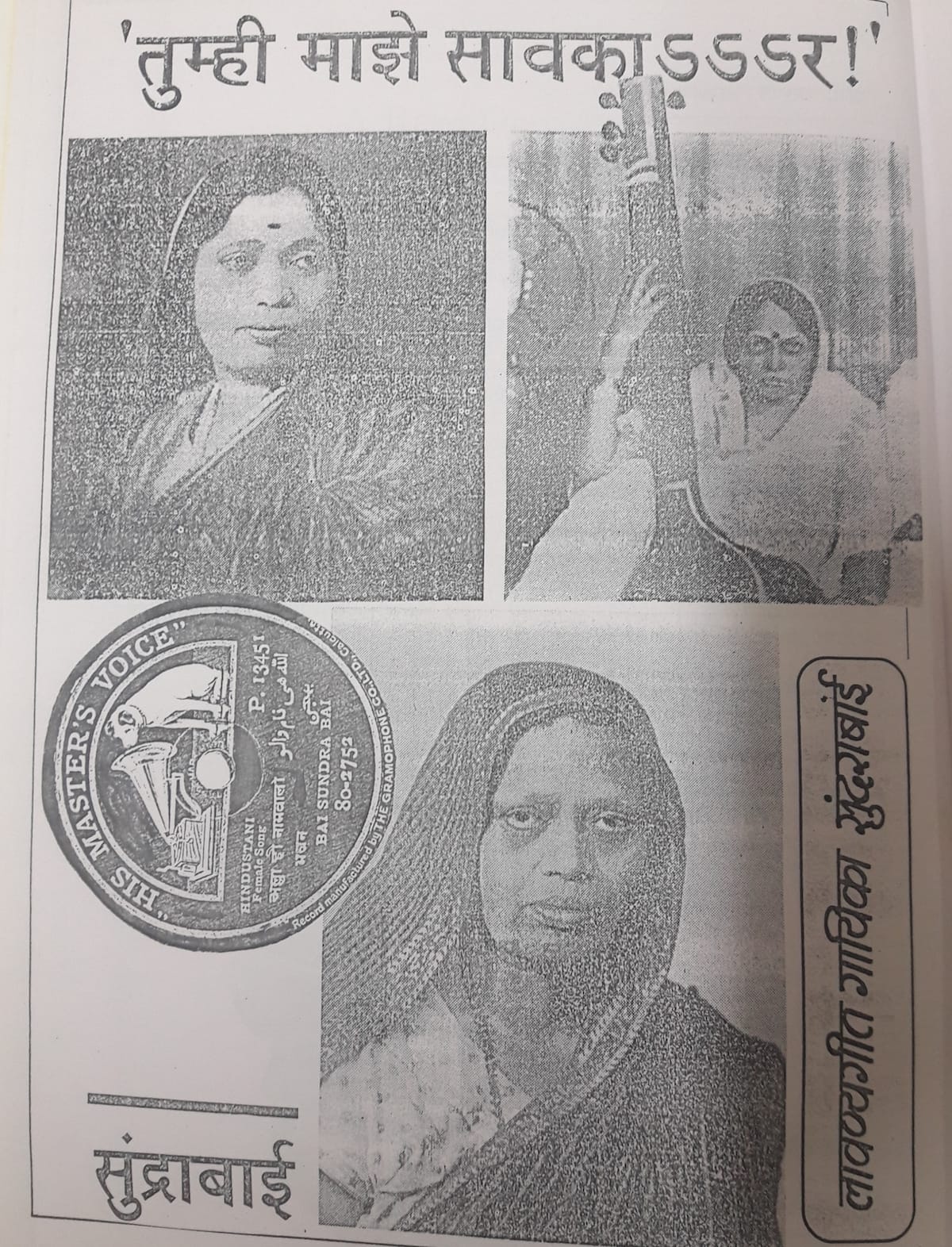

So popular were Sundarabai’s records that The Gramophone Company (His Masters’ Voice or HMV by then) awarded her with a gold medal around 1927-1928, for highest sales. Unfortunately, very few of these best sellers survive today nor have there been any serious attempts to protect those available for posterity.

In the same recording session with Odeon in August 1934, Sundarabai recorded her famous Hindi bhajan ‘Mathura hi Sahi’ – possibly learnt under Thakurdasoba. But quite interestingly, in a subtle manner, midway in the bhajan, a line is inserted: “Deen Bharat ka dukh door karo Prabhu!” (Oh Lord! End the sufferings of my oppressed country). This was quite in keeping with the political climate of freedom struggle and how the gramophone was an effective tool in conveying patriotic sentiments.

Mathura hi sahi

The finesse with which Sundarabai rendered the sensuous lavnis, gave them a new sense of respectability, stripping off the lewd and bawdy associations with it. Two of these Marathi songs that she recorded in Bombay for the Odeon Company in November 1936 are Kiti Naazuk Sundar Naar, and Masi Kan Ruslan Rajana.

Kithi najuk

Masi kam rusli saajan

In her long and momentous career, Sundarabai witnessed many changes in the world of music and entertainment — the gramophone recordings, the rise and fall of Marathi musical plays or natyasangeet, the radio, and the talkies or cinema. Ever ready to adapt to any medium, Sundarabai experimented and succeeded in each one of these. She worked with the Bombay Radio station since its inception. It is said that it was under her persuasion that Bal Gandharva, who considered Sundarabai as his sister, gave performances on radio. She remained employed with the radio in her last days as well. In fact, she is believed to have played the role of an active campaigner with several musicians, especially women, imploring them to eschew their inhibitions and adapt to modern technology – first with the gramophone and then the radio.

Also read: Bangalore Nagarathnamma, the singer who took to Sanskrit and feminism in 19th Century India

Sundarabai acted and also sang in two Marathi films produced by the doyenne of Indian cinema, V. Shantaram’s Prabhat Film Company — Manoos (which later got remade in Hindi as Aadmi) in 1939, and in Sangam in 1940-41. Manoos is a tragic story of a policeman Ganpat (played by Shahu Modak) who falls in love with a prostitute Maina (enacted by the talented Shanta Hublikar) while rescuing her from a brothel. Sundarabai plays the role of Ganpat’s mother in the film and sang two deeply philosophical songs – Man Paapi Bhoola and Tod Sod Moha. The immensely talented Master Krishnarao provided the music for the films and HMV came out with the records.

Sundarabai had earned a lot of wealth to be able to hire the entire third floor of Bombay’s Empire Hotel. She also owned two expensive cars that she was very fond of. Generous to a fault and always fond of children, Sundarabai’s velvet bag was always full of chocolates, expensive perfumes and gifts that she happily distributed to anyone she met. Her little notebook with jottings of songs and notations too was freely shared with anyone who asked for it. Obviously, with such generosity, she was bound to face tricksters, many of whom duped her of her wealth. Some of them coaxed her into starting a gramophone recording business and establish ‘Navbharat Record Company’. Sadly, the company went bust and she lost all her fortunes. She sold her cars, gave up her regal life, and moved to modest means, but she struggled to earn enough while working in the radio.

The pressure of it all eventually got to her and Sundarabai breathed her last in 1955 in Bombay – unsung, uncelebrated and completely forgotten. But her rich legacy across different media platforms still speaks to us, as eloquently and with as much finesse and love.

The author is a historian, political analyst and a Senior Fellow at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, with an upcoming biography of Savarkar. The music clips are from the ‘Archive of Indian Music’ that he has established to digitise and preserve vintage recordings of India. Views are personal.