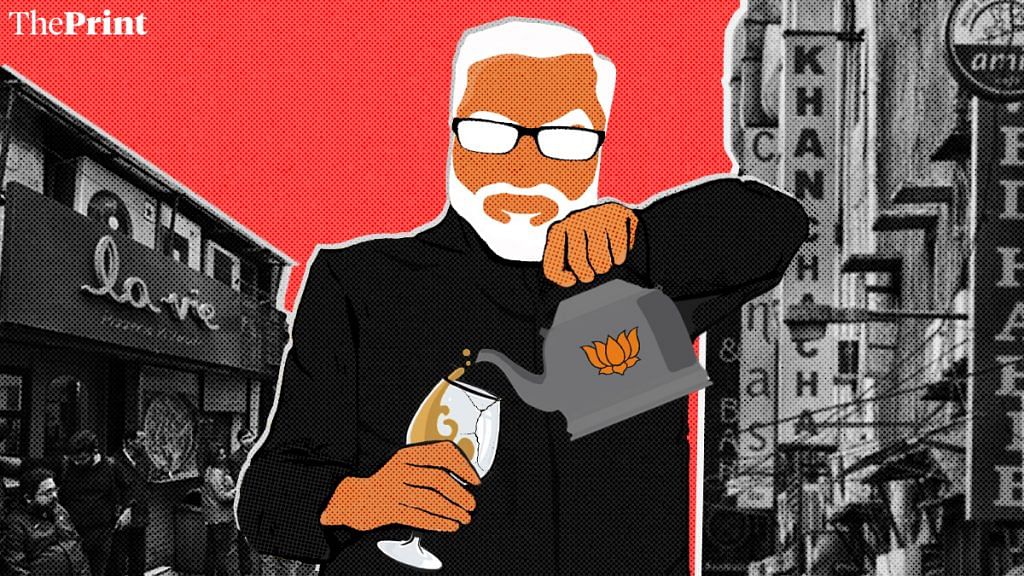

Modi’s image has not been created by the Khan Market gang, or Lutyens’ Delhi, but by 45 years of his toil.” That was Prime Minister Narendra Modi speaking of the elite that he and many of his admirers believe has ruled and ruined India.

Like everything the BJP does and says, it was both true and false.

There is certainly a fairly permanent elite that has controlled India for long. But it has been five years since Modi and the current home minister Amit Shah stormed India’s proverbial swamp called Lutyens’ Delhi. Since then, they have moved with the precision of a heat-seeking missile to dismantle the fortress of the intellectual and social privileged like never before.

But they continue to articulate, with mock-humility, their outsider-ness. First, they breached the magical Lakshman Rekha of 272 and now they have breached 300. They are not outsiders. Modi, Amit Shah and the BJP are now the new Lutyens’; they reside in and control the swamp. They are the power elite – political, intellectual, social and cultural.

Also read: Why does the Right-wing want to ‘occupy’ Delhi’s liberal hotspot Khan Market?

According to American sociologist C. Wright Mills, the power elite is one that controls corporate, military and political decision-making. While writing about post-war America, he described the elite as any one of six – the metropolitan 400 families, the celebrities, the corporate CEOs, the corporate rich, the political directorate and the warlords.

Adapt it to the post-liberalisation India, and you get the corporate elite, who are geographically based around Altamount Road, Mumbai; the political elite, revolving around 24 Akbar Road and 10 Janpath; and the intellectual/social elite, stretching from Khan Market to Lodhi Estate, a 1.4-km strip that takes in the India International Centre and the Lodhi Garden.

In post-Modi India, the corporate elite remains untouched in its pre-eminence. But the addresses that once attracted cheerleaders and favour-seekers, the bar that was once the hub of high-powered media editors, and the Lodhi Garden’s power walk that once saw politicians as diverse as Arun Jaitley and Digvijaya Singh, have all changed.

The Lodhi Garden’s walk, in fact, has earned itself an academic dissertation by Saurabh Dube, who writes in Mapping the Elite: Power, Privilege, and Inequality (edited by S.S. Jodhka and Jules Naudet) of what it implied. “First, the elite walking group is far from being unified in terms of class background and prior status. Rather, they represent distinct trajectories in the making and unmaking of Indian capital, present and past. Consider the contrasts between two of the key constituents of the group: a first-generation real estate developer with uncertain educational qualifications, who has amassed vast holdings; and a scion of a venerable family – its riches, status and influence reaching back to the past few centuries. Second, what binds the group is privilege, property and power as its members walk together to perform a shared elite-ness turning upon money and masculinity.” Well, it’s pretty much on its way out, and being replaced by badly shot videos of accepting fitness challenges.

Politically, the centre of power has moved from Akbar Road to Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Marg (not Ashoka Road) where the BJP has its swanky new three-storeyed headquarters. The pillars of the new establishment are in the vicinity. The Vivekananda International Foundation, where the new intellectuals plan the agenda for New India, has replaced the Rajiv Gandhi Foundation, once the hub of strategists like Mohan Gopal and Suman Dubey. The 1990-established Observer Research Foundation’s close links to the Ministry of External Affairs and its penchant for staging big-ticket events to coincide with big state visits have earned it a place that rivals the Centre for Policy Research, set up in 1973.

Also read: A Khan Market evening has more liberals than survive in the whole of Pakistan

The bureaucratic elite that once vied for bungalows in Lodhi Estate is now happy to live in the tony New Moti Bagh with homes that have four garages, two servants’ quarters and modular kitchens. The power in this government has clearly moved to Lok Kalyan Marg, from 10 Janpath. And on Raisina Hill, it is the Prime Minister’s Office, the PMO in the South Block, that calls the shots with the largest staff ever – 450.

The upscale Khan Market is now under attack even though the new Modi ecosystem has been trying to stake claim on it for a while now, and more so since his re-election. So, it’s not just that new addresses are becoming sites of influence, the old ones are also being occupied.

Khan Market itself is not what it used to be, losing some of its lustre to Jor Bagh, Meherchand Market, and the DLF mall at The Chanakya.

The new regime has its own key icons. Ram Madhav is the resident intellectual, the presiding deity of the India Foundation, which he runs with NSA Ajit Doval’s son Shaurya Doval. Amartya Sen has been edged out by professional troublemaker Subramanian Swamy and that eminent economist who is on the board of the Reserve Bank of India, S. Gurumurthy. Thought-provoking novelist and teller of transnational tales Amitav Ghosh has been replaced by cartographer of change Sanjeev Sanyal, and national conscience-keeper Arundhati Roy has made way for the nationalist flag-bearer Chetan Bhagat. And the palace’s poet laureate isn’t Javed Akhtar anymore (although he was feted during the Vajpayee era). Prasoon Joshi has been a favourite for some years now. But even he might have to cede turf to the new writer-cum-poet, Ramesh Pokhriyal ‘Nishank’, the HRD minister who has written 44 books.

Institutions where dissent first raised its voice, such as the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), home to Prakash Karat, Sitaram Yechury and the rest of the ‘tukde tukde gang’,have been put under the scanner. The staff composition is undergoing a change to reflect the government’s new ideology. The new dissent capital is the emerging liberal arts mecca Ashoka University.

The Pravasi Bharatiya Kendra is where major events now take place, with the geriatric India International Centre slowly dropping off the map. The Delhi Gymkhana Club continues to be an unoccupied Tharoor-quoting island, but it matters less and less in Lutyens’ non-accented conversations now.

Also read: Where’s the outcry for Ghaffar market? Khan Market’s paler brother

The greatest shake-up has happened politically, with the rise of the naya neta, a new, young and mobile leader who has emerged from rural India as traditional caste and land relations change. Many of these leaders started as small-time fixers, say Jodhka and Naudet in their book, or middlemen who helped people in rural areas get their work done while navigating the local-level bureaucracy. The social profile of those being elected to Parliament has also changed.

According to a study by academic Kuldeep Mathur, during 1952 and 1984, those coming from rural and agrarian background had pushed out in politics a good proportion of those coming from the urban professional background, who would belong to traditionally “upper” caste communities (Mapping the Elite). This change has continued. The 2014 elections saw more people from non-traditional business backgrounds making it to Parliament.

This change will also soon find itself reflected in the intellectual/social elite as well as in a new ideology flexing its muscles. How self-regenerating can this be, given that the BJP is already finding mini dynasties taking root, will determine how the elite ecosystem develops in a New India.

Expect little or no change in the corporate elite though. A study on top company CEOs and chairpersons in India by Naudet, Adrien Allorant and Mathieu Ferry has shown that while for the aspiring upper middle class, education is the open sesame that provides access to top positions, for company chairpersons/owners, the case is different. Not having a prestigious diploma does not preclude them from entering the small world of top capitalists. In other words, merit pales before birth when it comes to upward mobility in corporate India.

The short lesson in that? No matter the new think tanks, the new watering holes, the new icons, the corporate elite’s address will forever be Altamount Road.

Also read: Lutyens’ elites are now like marooned islands, rootless, adrift, irrelevant

But why do Narendra Modi and his followers continue to heap abuses at the Lutyens’ elite when they have occupied that space? Because, they need a powerful enemy that will make them look like a victim who stands outside a door that says Do Not Enter. This is exactly the reason why Donald Trump and his supporters keep chanting ‘drain the swamp’ although the US president is standing knee-deep in it.

The author is a senior journalist. Views are personal.