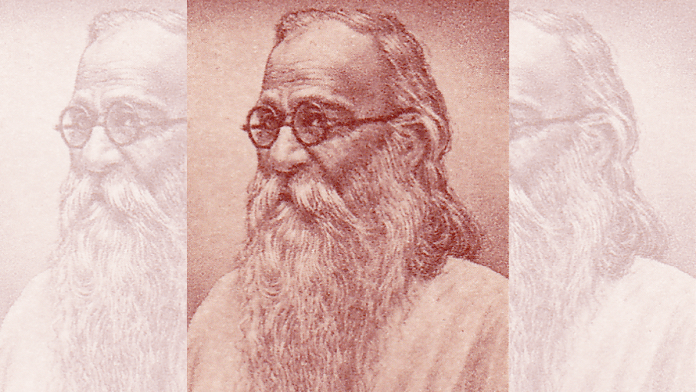

Researching the life and times of Lal Bahadur Shastri, one learns about the extraordinary influence that Bhagwan Das, the founding acharya of Kashi Vidyapeeth, had on the former Prime Minister. Das, awarded the Bharat Ratna in 1955, was a polyglot and prolific writer. He explored a range of subjects — from theosophy to eugenics to swaraj or self-governance — and founded the Vidyapeeth in 1921 when M.K. Gandhi asked Indian students to withdraw from British government-aided universities.

At Vidyapeeth, Shastri wrote his term-end research paper on the philosophy of Bhagwan Das, his mentor. The latter had written prolifically on issues relating to political economy, comparative religion, and non -cooperation.

On 1 January 1923, C.R. Das and Motilal Nehru founded the Swaraj Party to contest elections to the central and provincial legislative councils. The task of preparing the manifesto fell on C.R. Das and Bhagwan Das. Published on 30 January 1923, it contained the ‘fundamental principles and broad outline of a scheme of self-government, which should form the basis of Indian swaraj. The manifesto was first published in Mahatma Gandhi’s weekly Young India to elicit opinions from all sections of society.

Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj advocated “a decentralised form of government wherein each village unit would be responsible for its own affairs”. That imprint is clearly evident in the Swaraj Party manifesto. It reiterated that swaraj would mean “a maximum of local autonomy, carried on mainly with advice and coordination from, and only a minimum of control by the higher centres”. It goes on to state that every possible care should be taken to ensure that people’s elected representatives, who will constitute the chief authority for every grade – local, provincial and central — with power to make laws and rules, shall be “not self-seekers, but seekers of public welfare”.

Also read: Maulana Azad to Romila Thapar—Bharat Ratna and Padma awardees who refused to accept it

Voting age for women and men

Many of the points — in letter, if not spirit — were incorporated in the Directive Principles of State Policy and later in the Constitution itself through the 73rd and 74th constitutional amendments.

But there was one proposition that was truly extraordinary. At a time when the voting age for women in England was 30 years, and many other countries, including France, Greece, Italy, Turkey, and Japan denied the right to vote to women, the Swaraj Party manifesto offered something new. Chapter V read, “The qualifications of the choosers and the chosen, is quoted below: Every individual of either sex, who has resided in India for at least seven years, and is at least 25 years of age if a man, and 21 years if a woman, should be entitled to elect to the local Panchayat.”

The explanatory note written by Bhagwan Das reads: “With regard to the ages suggested for electors, the idea is that only those who are mature in body and mind, and have had some experience of life, especially of family responsibility, should be entrusted with the duty of choosing those who would rule their affairs. The ages suggested would ordinarily give these requisites in India. It seems that in England, the difference is reversed, 21 is fixed as the age for men and 30 for women.” He goes on to say: “In India, women are as mature in body and mind at 21 as men at 25, and these different ages, if fixed as suggested, would generally enable the husband and wife to go to the poll together.”

Also read: Why Lal Bahadur Shastri was more than Nehru’s shadow—green revolution to 1965 win

Separation of functions

The Swaraj Party charter also talked about the separation of State functions: “That the judicial function should be separated from the executive functions is admitted even by the bureaucracy. But it is not generally recognised that the legislative function should also be separated from the other two. Even more radically dangerous than the combination of judicial and executive is the combination of the legislative and the executive. Therefore, no legislator should have direct executive power, but the legislature should supervise and control the executive which should be responsible in every way to the Legislature.” The Swaraj Party charter suggested that the minimum age for legislators should be 40.

The Swaraj Party manifesto clearly says that panchayats at all four levels — village/town, district, provincial, and all-India — should appoint their own executive officers and exercise complete control over them. The elected panchayat members should indeed be playing a supervisory role over the executive.

Bhagwan Das further mentions: “This separation of powers would minimise temptations and the opportunities of corruption for all and would make the executive and judiciary responsible to the people in the persons of their elect.”

Although the complete details have not been spelt out, it is clear that the envisaged plan was the complete antithesis of the extant system in which civil service officers control the executive, judicial, and legislative function at all levels.

A manifesto ahead of its time

The manifesto was in wide circulation when the Government of India Act 1935 was being framed, but British jurists did not give much credence to it. The Act vested most authority with the executive and followed the British structure of the chief executive and their colleagues being members of the legislature. It is true that the Drafting Committee under B.R. Ambedkar did incorporate suggestions made in the Swaraj charter under the Directive Principles; the Preamble and Fundamental Rights were a significant departure from the 1935 Act. However, many stalwarts of the freedom movement, including Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, felt that the manifesto was utopian in its conception and may not be practical. Many provisions were retained with the addition of Articles 311 and 312, which ended up strengthening bureaucracy.

One is not sure how India would have fared if more elements of the Swaraj Party charter had been incorporated into the Constitution. But it is clear that our governance structure is a far cry from what C.R. Das and Bhagwan Das proposed. It certainly was a manifesto far ahead of its time.

Sanjeev Chopra is a former IAS officer and Festival Director of Valley of Words. Till recently, he was the Director of the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration. He tweets @ChopraSanjeev. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)