Savings deposits from small town India could prove to be a lucrative source of funding.

He may have struggled to mend India’s broken banking system, but at least Prime Minister Narendra Modi is shrinking the number of state-run banks to 19 from 26.

Although that’s nowhere close to the original idea of ending up with just six, it’s a good start. The next step will be to nudge most taxpayer-funded banks away from me-too corporate lending, the reason for their $210 billion bad-loan debacle.

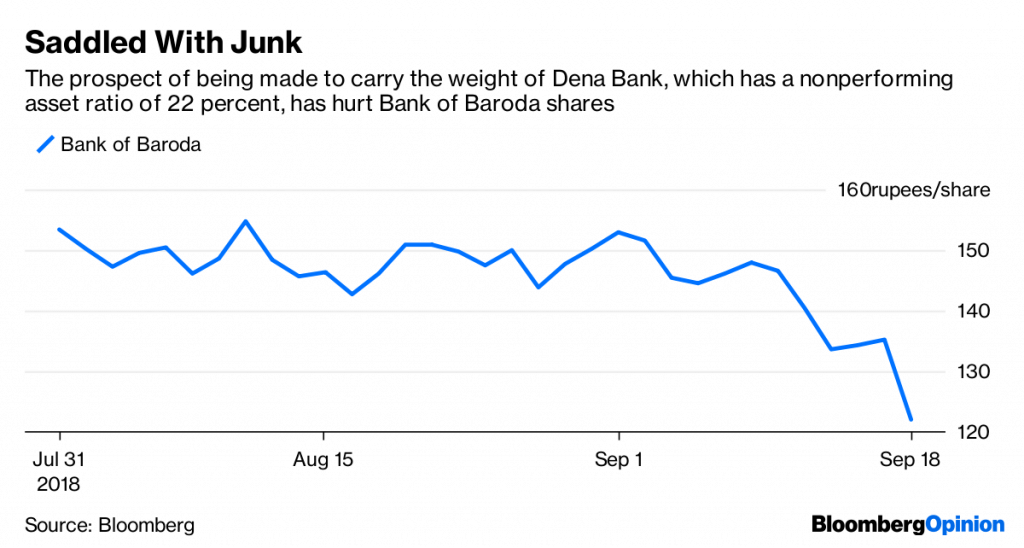

The latest plan, announced Monday evening, calls for moth-eaten Dena Bank Ltd., which has a bad-loan ratio of 22 per cent, and a far more pristine Vijaya Bank Ltd. (nonperforming assets less than 7 percent of the total) to be swallowed by Bank of Baroda.

Baroda, whose deposit franchise is more than twice as large as the other two combined, could then stake a claim to being the country’s third-largest bank. Strategy, however, matters more than size.

Minority shareholders have reasons to grumble. The combined entity will have soured loans of about 13 per cent, worse than Baroda’s 12.4 per cent in nonperforming assets. Plus the acquirer’s current employee count of 56,000 will balloon by half. All jobs are deemed safe, so the only way to achieve cost efficiencies would be to prune surplus branches and wait for excess staff to retire.

There’s a way, however, for ex-Citibanker P.S. Jayakumar, Bank of Baroda’s current boss, to make a success of the merger: Reduce the emphasis on lending and embrace investing.

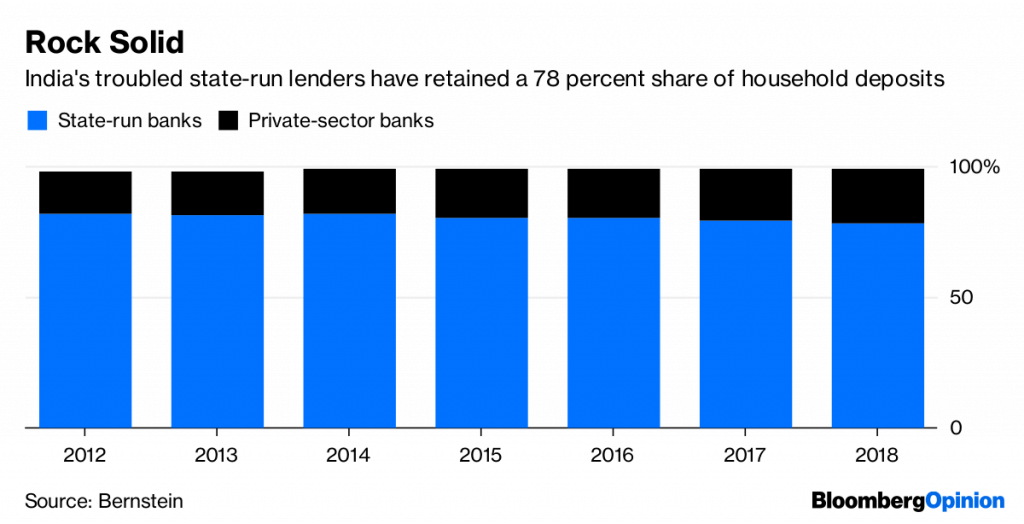

State-run banks’ strength lies in their branch network, especially outside of metropolitan areas. About 62 per cent of India’s savings deposits originate in smaller cities, towns and villages, according to Bernstein analysts Gautam Chhugani and Gaurav Jangale. This is the most lucrative source of funding, because even as borrowing costs rise, banks can take their time to reprice the rates they pay on household savings. In the past seven years, state-run banks have lost only 5 percentage points of market share in savings deposits, compared with an 11 percentage-point drop in their share of lending, Bernstein’s data show.

While privately run lenders would love to make deeper inroads into their state-run rivals’ 78 percent share of household deposits, the cost of setting up a branch network in smaller towns and rural areas is too high. However, just because the combined entity in Bank of Baroda’s three-way merger would have 2 trillion rupees ($28 billion) more in deposits than its gross assets, it shouldn’t look to boost its own lending.

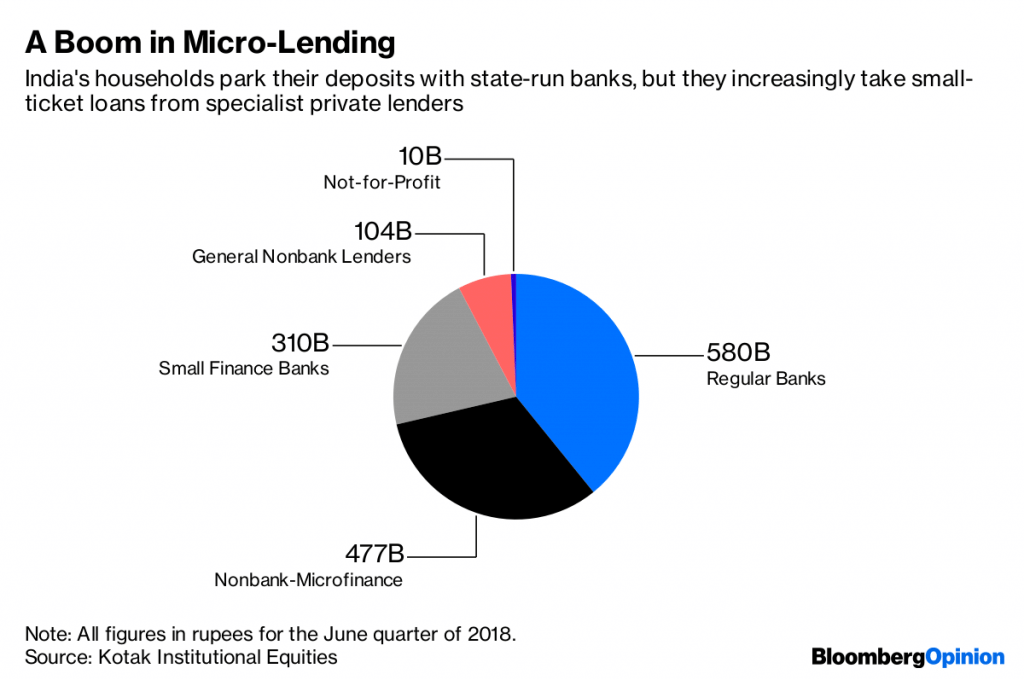

A smarter strategy for Jayakumar would be to drive growth via securitization. There are now plenty of new-age, specialist retail lenders in India. Some of them, such as Bandhan Bank Ltd. and AU Small Finance Bank Ltd. are among the most valuable lenders in the world because of their expertise in selecting creditworthy borrowers. If they, plus specialist nonbanks like Shriram Transport Finance Co. and Bajaj Finance Ltd., can pool everything from loans for truck purchases and working-capital finance against property, then Jayakumar could earn decent returns on spare deposits by buying parcels of retail loans presented to him as securities.

Let big-ticket corporate exposure move away from the banking system to direct fundraising by companies in the bond market; and let state-run banks become financiers to retail lenders. Just because the subprime crisis in the U.S. featured dodgy packaging of risky interest-only mortgage loans as AAA-rated securities doesn’t mean all securitization must end in disaster.

The industry is booming: Securitization transactions in India doubled in the June quarter from a year earlier. So if bankers like Jayakumar take the initiative to iron out legal and accounting issues, there’s no reason why such endeavors shouldn’t help channel the idle deposits of state-run lenders away from chunky corporate loans and toward small shopkeepers, cold-storage owners, farmers, horticulturists and students. That might even be a more profitable way of making money than hobnobbing with the likes of the Gupta family in South Africa – a relationship that was partly responsible for Bank of Baroda pulling out of that country.

For state-run banks that are used to lending against collateral, it’s near-impossible to start evaluating retail borrowers’ future cash flows. The kind of data mining that’s needed to safely underwrite these (mostly) unsecured loans is more readily available with specialist lenders.

Jayakumar’s real opportunity in the three-way merger is not the bloated balance sheet, but the chance to create a very different bank, one that’s more of a savvy investor than a traditional lender. – Bloomberg