Et tu, Glencore?

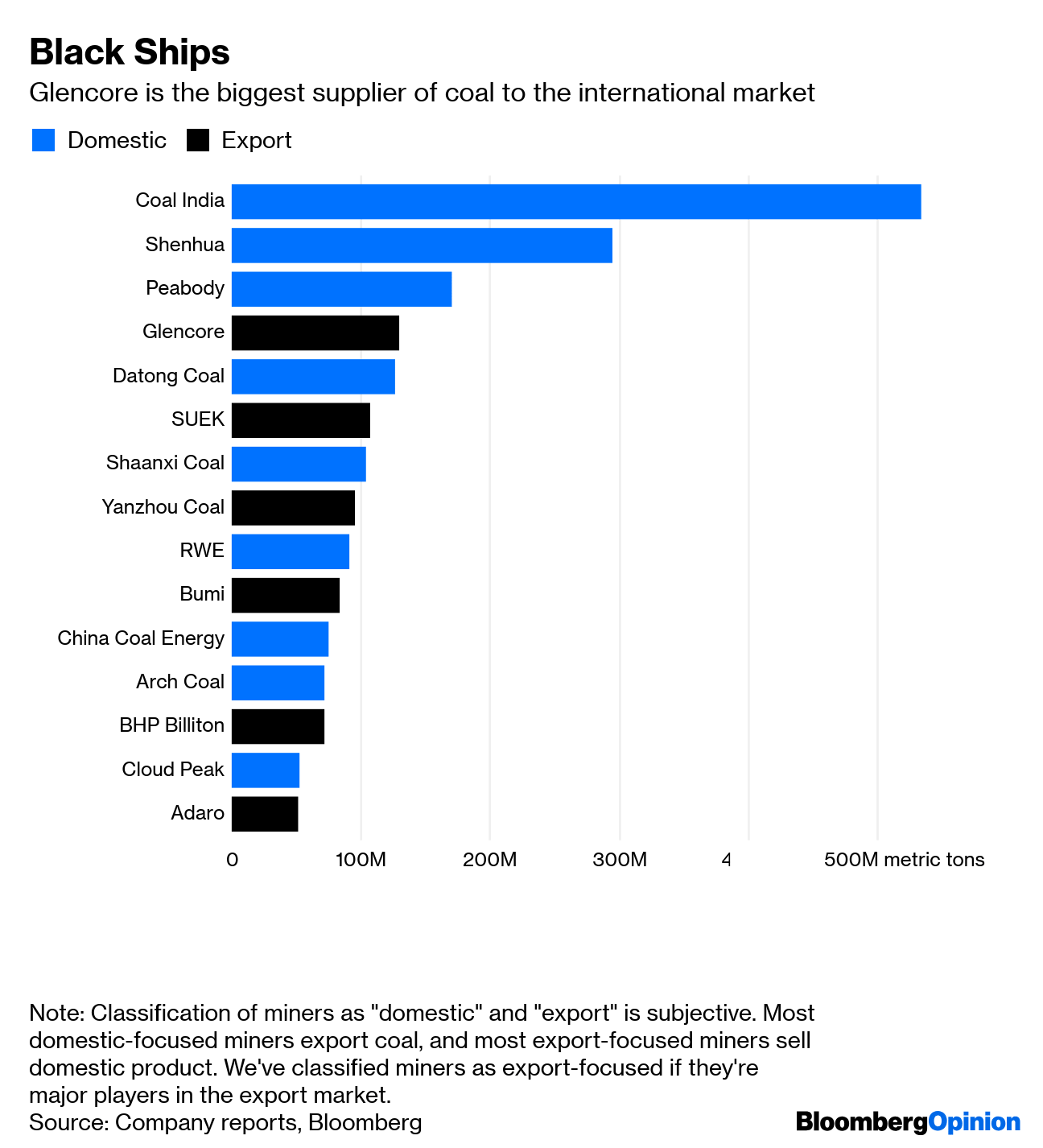

It’s only a few months ago that the world’s biggest commodity trader was promoting coal as – don’t laugh – a viable part of global emissions-reduction plans. Now Glencore Plc, the largest supplier of thermal coal to the international market, is promising to cap production for the foreseeable future at around current levels of 145 million metric tons a year, David Stringer of Bloomberg News reported Wednesday.

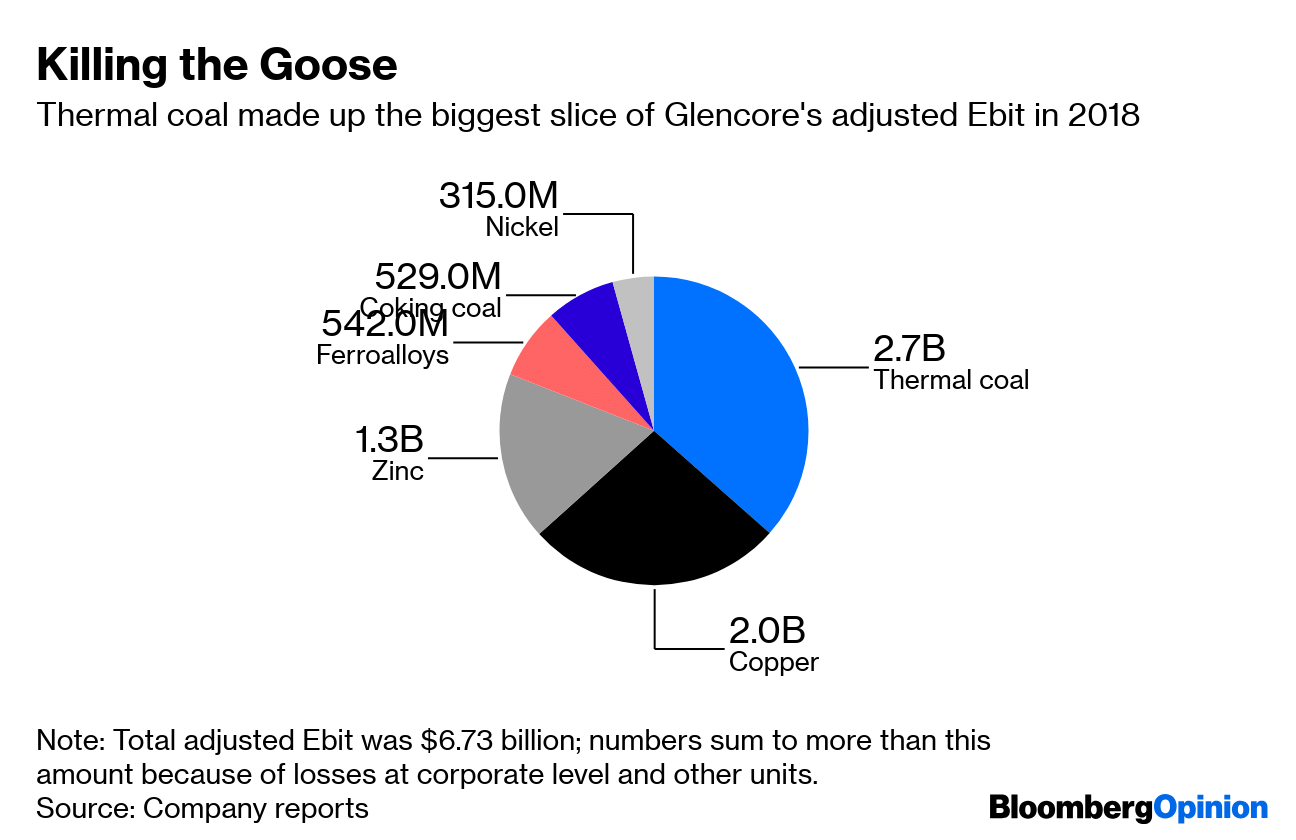

The move is particularly striking because coal made up the biggest slice of Glencore’s profits in 2018 annual results published Wednesday, and the company is one of the few diversified miners proudly committed to the black stuff.

Anglo American Plc attempted to sell all its coal assets during its abortive restructuring in 2016, but gave up because no one was willing to buy them at a price it found acceptable. Rio Tinto Group got rid of its last coal mines (to Glencore, no less) last year. BHP Group seems committed to its huge mines producing steelmaking coal, but appears less attached to the ones producing the thermal coal used in power generation.

What’s changed?

One factor is surely that major investors are increasingly putting pressure on companies to back away from the dirtiest emissions. Those that are still invested are increasingly likely to buck management on climate-related shareholder resolutions.

Glencore’s move follows “engagement with investor signatories of the Climate Action 100+ initiative,” the company said in a statement Wednesday. “We must invest in assets that will be resilient to regulatory, physical and operational risks related to climate change.”

Institutions with $6.2 trillion in assets have already committed to diversify from fossil fuels, according to philanthropic consultancy Arabella Advisors; members of Climate Action 100+ manage more than $32 trillion. Axa SA and Swiss Re AG won’t invest in or provide insurance to companies that derive more than 30 per cent of their revenues from coal. Norges Bank Investment Management, the sovereign wealth fund that nonetheless remains one of Glencore’s biggest investors, in theory uses the same 30 per cent bar for screening its shareholdings.

Even Glencore hasn’t been pushing thermal coal as hard as its rhetoric might sometimes suggest – and that rhetoric has been riddled with contradictions, as my colleague Chris Bryant has pointed out. The company has made little secret of its opposition to Adani Enterprises Ltd.’s proposed Carmichael project in Australia, which would dump additional supply on a global seaborne market that can’t really digest it.

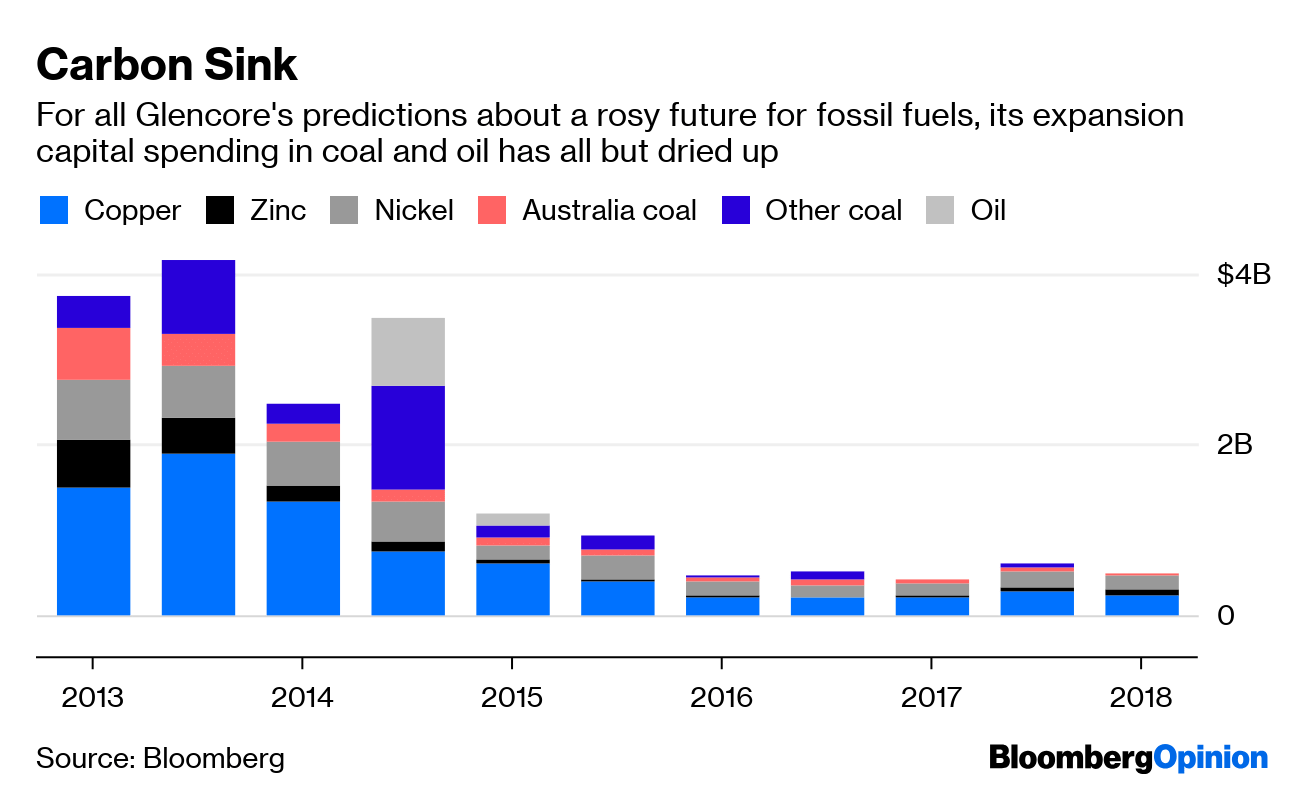

The attempt to throttle back additional tonnage isn’t just about excluding competitors. Coal received just 10 per cent of Glencore’s expansion capital expenditure in 2017, despite accounting for almost a third of Ebitda, suggesting the business was being run for cash rather than growth.

Furthermore, Wednesday’s announcement doesn’t mean Glencore is turning its back on coal. Thanks to its investment in Rio Tinto’s mines north of Sydney in 2017, it’s likely to still be churning out the black stuff for decades. The planned output cap could be maintained well into the 2030s just by building out its current undeveloped projects.

Still, the announcement gives another clue to how coal will decline in the coming years. It’s not going to be a sudden end, where prices of traded soot fall permanently below marginal costs and guillotine the industry. Instead, we’re more likely to see death by a thousand cuts.

More shareholders will divest from miners and from their customers who burn the fuel; the group of insurers who refuse to provide coverage for mining projects and thermal generators will expand, further pushing up costs; new supplies will come increasingly from relative minnows like Whitehaven Coal Ltd. and MACH Energy Australia Pty., which will struggle to get access to capital, plus a handful of state-owned giants in China and India.

At times, that throttled supply pipeline may push prices higher, with generators fighting over a dwindling pool of fuel. Right now, that dynamic is keeping benchmark coal at Australia’s Newcastle port around $94 a ton, delivering some healthy profits to Glencore.

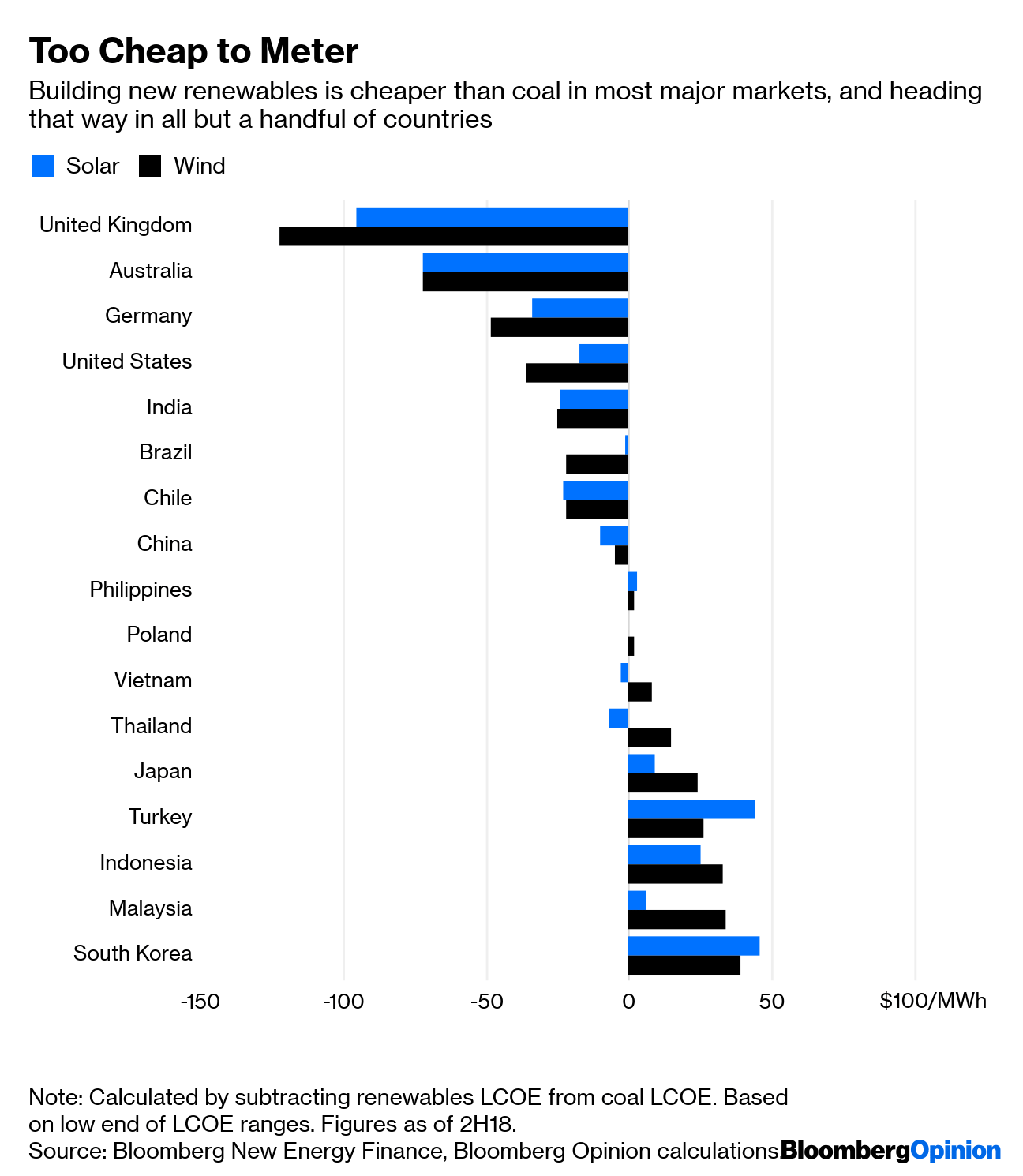

That won’t help in the long term. The prices of wind and solar power and the battery storage to back them up keep on falling, as manufacturing efficiencies drive down costs. It’s hard enough for coal to compete with that; with higher prices, it’s all but impossible.

New wind and solar are already cheaper than coal in Australia, Brazil, Chile, China, Germany, India, Thailand, the UK, the US and Vietnam, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance data. In Malaysia, the Philippines, Poland, and even Japan, the tipping point could come within months.

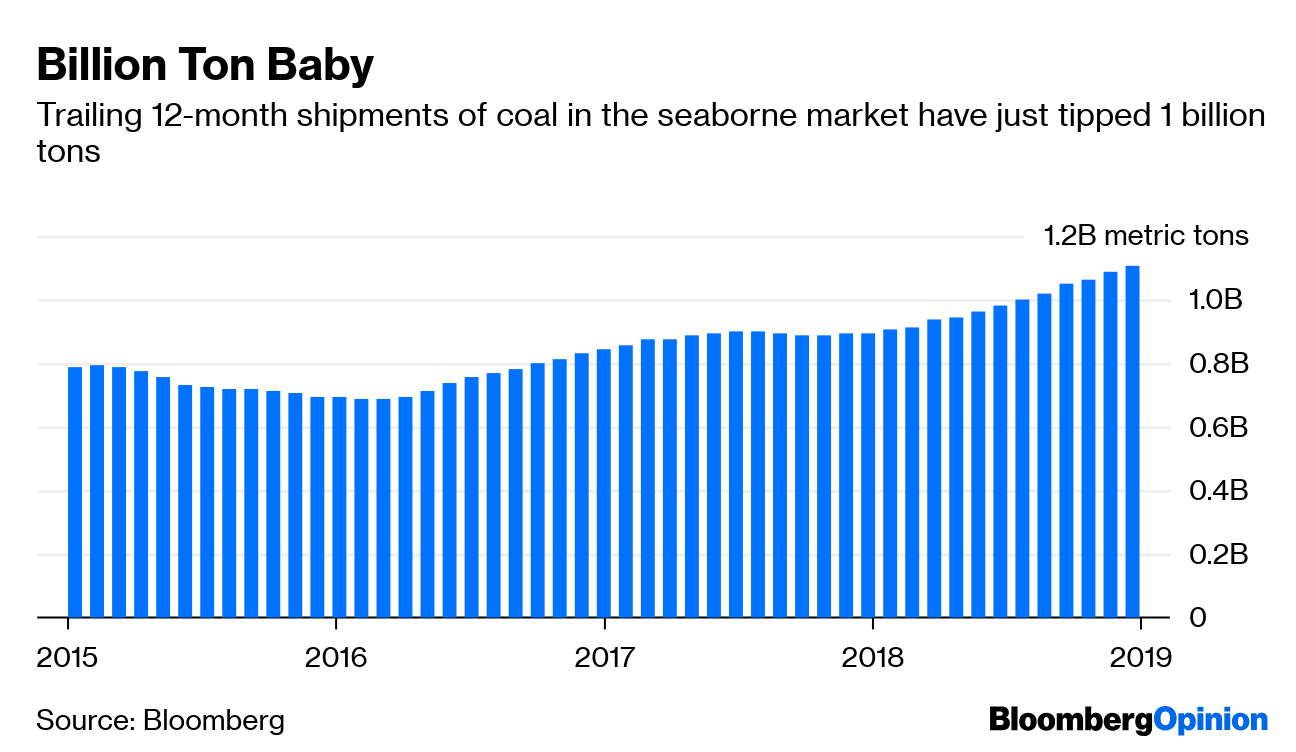

Coal shipments last year topped one billion tons for the first time in history. The future looks darker. When the biggest producer calls time on the market, it’s time to shut up shop. –Bloomberg

Also read: Modi govt promised to end coal imports by 2016, but they’ve been on the rise since then