In India’s federal fiscal structure, states shoulder significant responsibilities for delivering public services and welfare benefits to citizens. Often, these benefits take the form of subsidies – financial interventions designed to reduce costs for consumers or produceRs

While subsidies can be effective tools for poverty alleviation and reducing inequality, their fiscal sustainability has become increasingly questionable, particularly in the challenging post-pandemic economic environment.

In a recent study (Amarnath et al. 2024), I along with my co-authors, analyse budgetary data from seven Indian states – Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal and Nagaland – for the period between 2018-19 and 2022-23

Overview of findings

Overall, we see that revenue deficits have become persistent, and fiscal space has shrunk dramatically. States with revenue deficits are spending over 20 per cent of their revenue expenditure on subsidies, while their fiscal space has shrunk to less than 50 per cent of revenue receipts. Committed expenditures – including salaries, pensions, and interest payments – now consume over 80 per cent of revenue receipts in states like Punjab (81.5 per cent) and Kerala (71.8 per cent). This leaves limited room for developmental spending, a concern highlighted by recent analysis by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI, 2022).

In this context, the growing burden of explicit subsidies is particularly concerning. Explicit subsidies – direct payments to individuals or organisations that reduce costs or prices – have increased sharply since 2020-21. For instance, Punjab’s explicit subsidies grew from Rs 13,168 crore in 2019-20 to Rs 47,222 crore in 2021-22. Similarly, West Bengal’s subsidies increased from Rs 31,381 crore to Rs 45,308 crore during the same period.

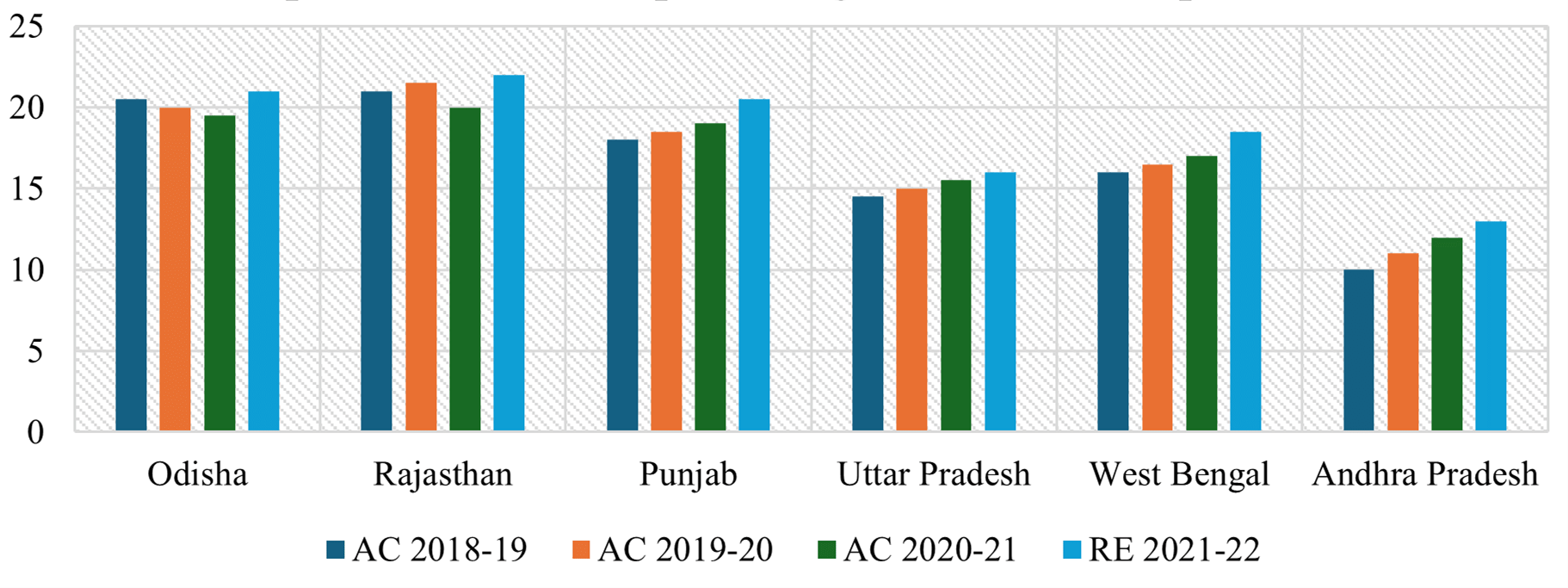

Figure 1. Explicit subsidies as a percentage of revenue expenditure

This trend has significant implications for state finances and development priorities. States are increasingly borrowing to finance subsidies – Punjab and Andhra Pradesh’s subsidy expenditure exceeds their revenue deficits. This reduces fiscal space for capital and other developmental expenditure, potentially compromising long-term growth (Rao and Kumar 2017).

Also read: Karnataka govt study finds misuse of irrigation pump subsidies, wealthy farmers take lion’s share

Defining and measuring explicit subsidies

Traditional measures of subsidies in state budgets significantly underestimate their true extent. Following Mundle and Rao’s (1991) pioneering work on subsidy measurement, our analysis shows that many subsidy-like expenditures are often categorised as grants-in-aid or assistance to public sector units. The Comptroller and Auditor General’s (CAG) reports capture only explicitly stated subsidies, missing substantial expenditure routed through other budget heads. A more comprehensive definition includes direct payments to individuals, assistance to organisations providing subsidised goods/services, and explicitly stated subsidies in budgetary transactions.

Using this broader definition reveals striking patterns across states. Punjab and Andhra Pradesh show the highest subsidy burden, with explicit subsidies consuming over 25 per cent of revenue expenditure in 2021-22. In contrast, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh maintain relatively lower subsidy levels at around 15 per cent of revenue expenditure. Notably, these latter states also maintain revenue surpluses, supporting earlier findings on the relationship between fiscal discipline and subsidy sustainability (Rao 2017).

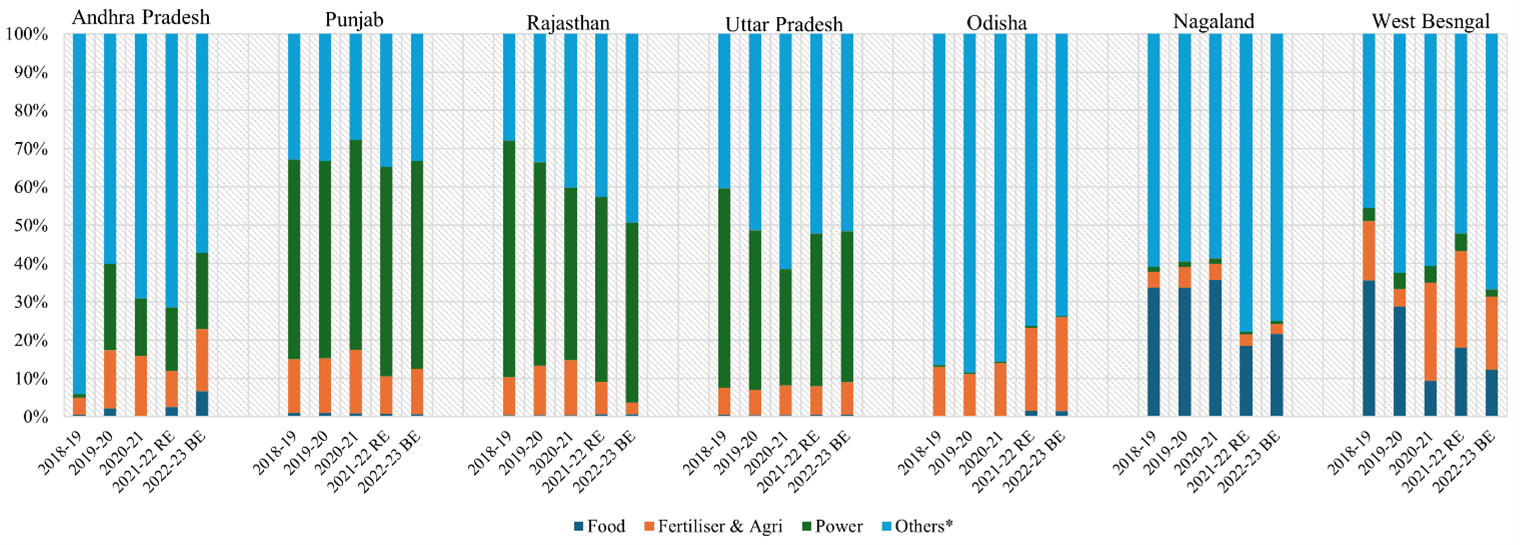

Figure 2. Composition of explicit subsidies across major categories, for selected states

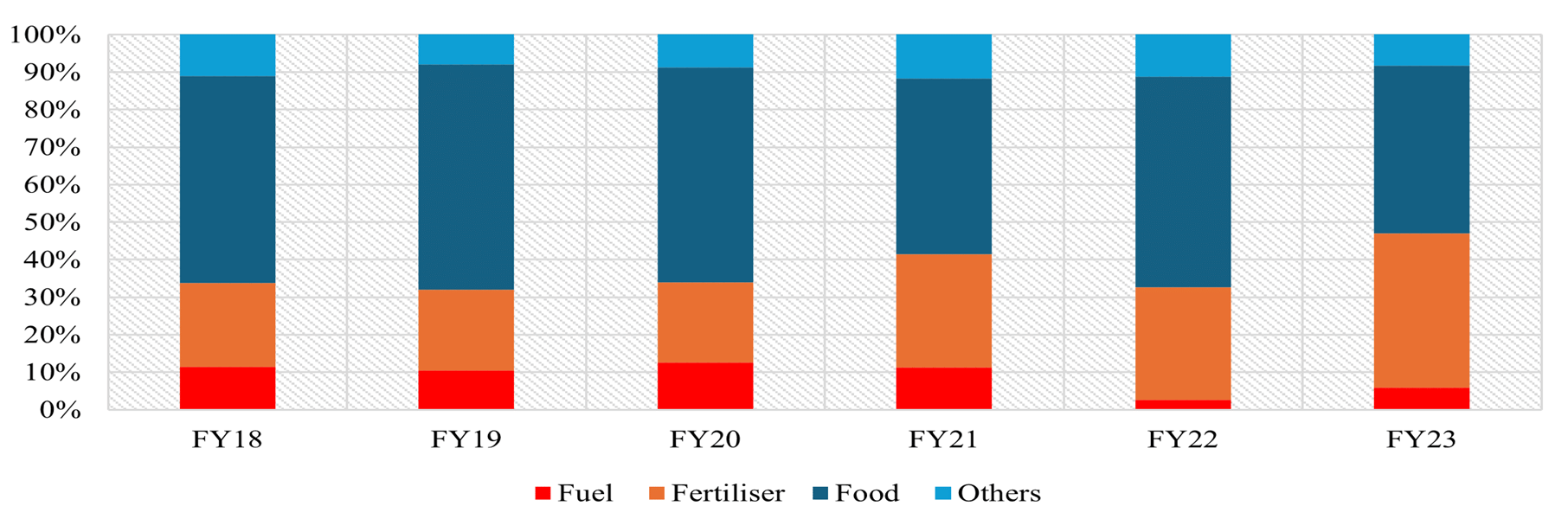

Figure 3. Composition of Union Government’s subsidy expenditure

State-level patterns and major concerns

Analysis of state-level data reveals three distinct patterns in subsidy distribution. First, states with revenue deficits tend to have higher subsidy burdens. Andhra Pradesh and Punjab, both facing persistent revenue deficits, spend over 20 per cent of revenue expenditure on subsidies. In contrast, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh maintain subsidy levels below 15 per cent while preserving revenue surpluses. This pattern aligns with earlier findings on the relationship between fiscal health and subsidy expansion (RBI, 2022).

Second, power sector subsidies emerge as a particular concern, dominating state expenditures. In Punjab, power subsidies to agriculture alone cost Rs 6,700 crore annually, while unpaid power subsidies accumulated to Rs 7,930 crore by 2020-21, effectively converting explicit subsidies into public debt. The recent announcement of 300 units of free power in Punjab could add another Rs 14,337 crore to annual subsidy costs, amidst the growing practice of not reimbursing power distribution companies. This aligns with issues raised by UDAY scheme assessments (CAG 2020), which found that power sector reforms remain incomplete, with state governments continuing to absorb distribution company losses rather than addressing structural pricing and efficiency problems. The Fifteenth Finance Commission (2020-2025) specifically highlighted how delayed subsidy payments create a vicious cycle of utility debt, deteriorating service quality, and increased state contingent liabilities.

Third, states are increasingly using direct benefit transfers (DBT) for subsidy delivery. Andhra Pradesh’s DBT payments grew from Rs 11,256 crore in 2018-19 to Rs 40,043 crore in 2021-22. While DBTs can improve targeting (Muralidharan et al. 2016), some new schemes raise concerns about sustainability. The proliferation of universal schemes, like Punjab’s 300-unit free power policy, risks creating long-term fiscal pressures that could outlast electoral cycles.

Policy implications and way forward

The growing burden of explicit subsidies demands urgent policy attention. Our analysis points to three key principles for subsidy rationalisation, building on recommendations from the Fifteenth Finance Commission (2020), and recent policy research. First, states should link subsidy expansion to fiscal capacity. The contrasting experiences of Odisha and Uttar Pradesh versus Punjab and Andhra Pradesh demonstrate that maintaining revenue surpluses is crucial for sustainable subsidy programmes, supporting earlier findings on fiscal sustainability (Rangarajan and Srivastava 2011).

Second, power sector reforms are critical. The practice of accumulating unpaid power subsidies effectively converts explicit subsidies into public debt, compromising both power sector viability and state finances. The experience of the Ujjwal DISCOM Assurance Yojana (UDAY) scheme implementation shows that without fundamental reforms in subsidy delivery and targeting, financial restructuring alone provides only temporary relief (NITI Aayog, 2021). Punjab’s substantial power subsidy arrears illustrate the risks of delayed reforms.

Third, subsidy design should follow the ‘TTTE principle’ – proper Targeting, maintained Transparency, fixed Timelines, and regular Evaluation. While DBTs can improve targeting, new universal schemes risk creating unsustainable fiscal burdens. Evidence from successful DBT programmes suggests that well-designed targeting mechanisms can significantly reduce leakages while ensuring benefits reach intended beneficiaries (Muralidharan et al. 2021).

The path forward requires difficult political choices. However, evidence from revenue surplus states shows that maintaining fiscal discipline while providing targeted subsidies is possible. As demonstrated by international experience with subsidy reform (International Monetary Fund, 2022), the key lies in building political consensus around fiscal sustainability while protecting vulnerable populations through well-designed social protection programmes.

Kishan Narayan is a PhD student at the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs, Northeastern University, Boston (US). He tweets @kishanjnu. Views are personal.

This article was first published by Ideas for India.