The United Nations Human Rights Council’s 43rd session will end on 20 March, but Sri Lanka has already made some noise. The country recently announced that it is withdrawing from previous commitments made through UNHRC resolutions that the Rajapaksa government now says were never presented in Parliament or approved by the Cabinet of Ministers before being co-sponsored by the previous government.

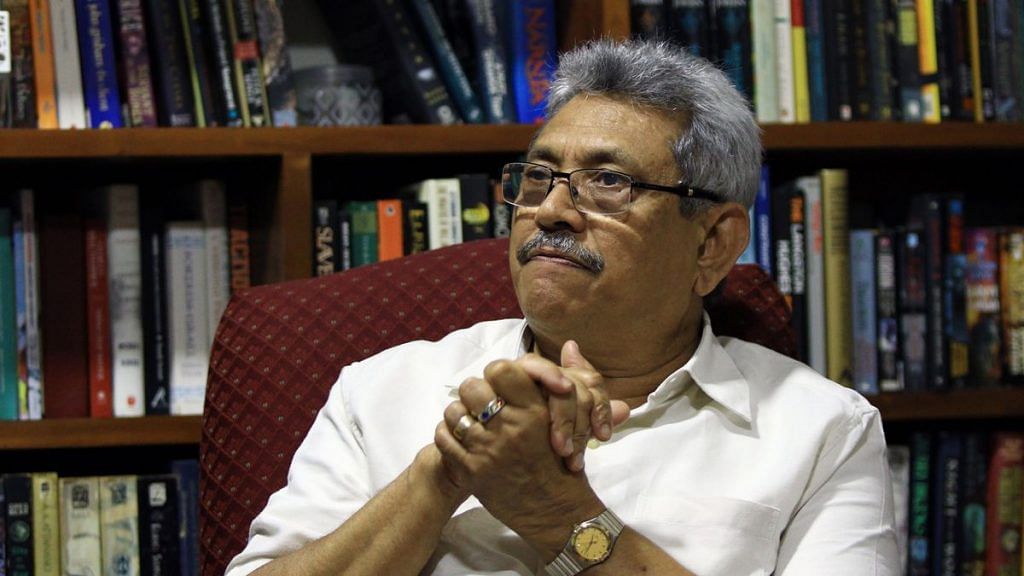

With this development, the administration of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa is sending another clear but unsurprising signal that transitional justice and broader rights concerns have been put on the back burner. The UN resolutions it has withdrawn from — 30/1, 34/1 and 40/1 — intended to promote ‘reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka’.

Also read: Ruthless Rajapaksas back in power, they’ll go after Sri Lankan NGOs, Tamils & institutions

Previous engagement with UNHRC

The first co-sponsored resolution on Sri Lanka was passed in 2015. This happened shortly after Maithripala Sirisena became the president and a coalition government was formed. The resolution promulgated a strong transitional justice agenda, including a truth commission and an accountability mechanism to address alleged wartime rights abuses.

Yet, most of those commitments remained unfulfilled, and it’s obvious that the coalition government was never serious about meaningfully engaging with the promises it had made at the UNHRC; in fact, the government didn’t even care to properly explain the transitional justice agenda (or why it mattered) to the general public.

Nevertheless, Sri Lanka’s engagement with the UNHRC processes was championed by international actors; the administration was clearly trying to distance itself from the previous government’s intransigent approach towards the council.

When Mahinda Rajapaksa (Gotabaya’s brother and the current prime minister) was the president, resolutions on Sri Lanka – related to human rights and transitional justice – were passed in 2012, 2013 and 2014. The Rajapaksa administration at the time, however, repudiated all of them.

The current Rajapaksa administration has made it clear that it will pursue national reconciliation and transitional justice on its own terms, yet these are just empty promises. The Rajapaksa brothers are both alleged war criminals and committed Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalists. In that context, the Sri Lankan government’s talk of another ‘Commission of Inquiry’ and platitudes about continued “engagement” with the UNHRC need to be recognised as deeply insincere gestures that they are infamous for making.

We don’t need another Commission of Inquiry in Sri Lanka to reiterate what the world already knows: there will be no justice through a purely Sri Lankan mechanism. The country’s institutions are utterly incapable of holding military personnel to account – for a range of horrific violations, including alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Also read: The Rajapaksa brothers who ‘controlled every aspect of Sri Lankan life’ return to power

Messy domestic politics

The Rajapaksa government’s decision also puts Sri Lanka’s messy domestic politics in the spotlight. Now is a particularly convenient time for Colombo to denigrate the UNHRC processes. As was widely anticipated, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa dissolved Parliament on 2 March. A parliamentary election is set for 25 April.

Criticising the Geneva-based HRC, venerating Sri Lanka’s “war heroes”, reiterating that foreign interference in the country’s domestic affairs won’t be tolerated, and championing Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalism – these are all politically convenient actions that will help the Rajapaksas in an electoral contest that they are already favoured to win.

Getting a two-thirds majority in Parliament would be huge and it certainly isn’t out of the question. That would make it easy for the Rajapaksas and their allies to change the Constitution for undemocratic purposes that suit their agenda. It would further usher in Rajapaksa-style authoritarianism in Sri Lanka.

Also read: Be it Shavendra Silva or Rajapaksa, Sri Lanka’s love for ‘war criminals’ runs deep

What comes next?

The bitter truth is that Sri Lanka’s engagement with the UNHRC has been a sideshow for years. Now that the Rajapaksas are back in power, it’s certain that the island nation will make no progress on transitional justice and healing the wounds of a civil war. The broader human rights situation is already worsening.

Do international actors care? Will diplomatic pressure be applied on Sri Lanka? The United States recently sanctioned Shavendra Silva, Sri Lanka’s military chief, over alleged wartime abuses. But the move hardly constitutes a strategy; it’s probably driven by geopolitics and concerns about Chinese influence in Sri Lanka. Besides, it’s hard to believe that the Trump administration is ever going to meaningfully pull Sri Lanka up for its poor human rights record.

Sri Lanka’s civil war ended in 2009 with the mass slaughter of Tamil civilians. People still talk about the failure of the “international community” to act or that more could have been done to stop the violence.

More than ten years on, there’s been no accountability and the root causes of the country’s ethnic conflict are far from resolved. Sri Lanka is now headed towards a more severe authoritarian direction. Of course, the Rajapaksas are no strangers to authoritarianism. I’m not holding my breath for international actors to quell these negative trends – or even attempt to do so.

The author is an Adjunct Fellow at Pacific Forum. Views are personal.