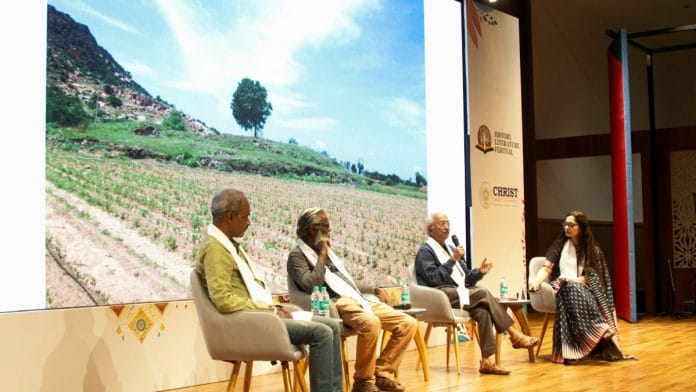

Earlier this month, at the third History Literature Festival held at Christ University, a session titled ‘Stones and Shadows’ traced South India’s journey from prehistoric settlements to Megalithic traditions. The discussion examined the indigenous evolution of cultures in peninsular India, challenging the ‘north centric gaze’ on its history.

While Megaliths – large stones used to construct a structure or monument – are generally associated with the Iron Age, the exact origins of the Megalithic tradition are shrouded in mystery. Senior archaeologist Ravi Korisettar – honorary director at the Robert Bruce Foote Sangankallu Archaeological Museum – hinted during the event that its antecedents could be found in the ‘Southern Neolithic’ period; an era characterised by ash-mounds, grinding and polished tools, and Black and Red Ware pottery.

If the beginning of farming in peninsular India triggered a unique cultural dynamic that paved the way for the Megalithic culture and the Iron Age, it is worthwhile to analyse the Southern Neolithic period as the possible foundation for these major historical developments.

Tracing origins

The term Neolithic, which translates to New Stone Age, is used to define early farming societies in archaeology. Coined by English polymath John Lubbock in 1865, it describes one of the stages of the first age of the Three Age System, where early societies progressed from the Stone Age (which includes the neolithic period) to the Copper and Iron Ages.

According to Lubbock, cultural evolution was a linear process where humans adapted to diverse ecologies at the same time, and history advanced in a straight line. While this model holds some relevance in the European context, it has led to considerable confusion in the Indic region. After 160 years, however, many archaeologists have come to the consensus that this simplistic view doesn’t apply to the Indian subcontinent. Cultural evolution is way more complex and characterised by regional and indigenous developments at varying timelines that don’t fit into Lubbock’s linear framework.

The advent of farming is seen at varying timelines in different pockets of India. At Mehrgarh in present day Balochistan, domestication of both plants and animals began around the eighth millennium BCE. In sites such as Uttar Pradesh’s Lauhradewa, they are dated to seventh millennium BCE. At Burzahom, the Northern Neolithic is dated to third millennium BCE, making it contemporaneous to the Harappan Civilisation. Similarly in South India, the beginning of farming goes back to 2000 BCE, with the exception of sites such as Watgal, which is dated to 2700 BCE. Kodekal, going back to 3000 BCE, breaks the linearity of history.

Having said that, it is important to note that between Mehrgarh and Kodekal, the landscape was dotted with settlements that were either heavily into copper/bronze or continued the hunting-gathering way of life (as seen at Langhnaj in Gujarat).

During the excavation of Tekkalakotta in Karnataka in 1965, two phases of the Neolithic period were noticed. In the first phase, plain and burnished grey handmade pottery was discovered, some of it with post-firing painting in purple, black and violet. Microliths, which are micro stone tools and markers of the new Stone Age, were found along with bone tools and jewellery such as beads made in semi-precious stone and gold. During this phase, copper objects were also found. In the second phase, Black and Red Ware pottery is present, and the site is roughly dated to 2100 BCE. In early literature, the presence of Black and Red Ware was always correlated with the Neolithic period in South India, which continues into the Iron Age with Megaliths sandwiched in-between.

Also read: When archaeology wasn’t ‘ladylike,’ women still shaped the field, one dig at a time

Stones and shadows

At the Sanganakallu-Kupgal archaeological complex in Karnataka, Neolithic and Megalithic remains are scattered between five hills on the Bellary-Moka Road. This is perhaps the most extensive settlement—spread over an area of 1,000 acres, and spanning 2,000 years of South Indian history. The habitation site in the Sannarachammagudda complex was first excavated in 1946 by B Subbarao. He divided the site into three phases, spanning from Pre-Neolithic to Megalithic times (Subbarao B, 1948). In the last phase, Subbarao noticed Black and Red Ware and Black Polished Ware in the ceramic complex.

When the site was reinvestigated by archaeologists Z.D Ansari and M.S. Nagaraja Rao in 1969, they hinted at the possibility of an ash mound. An ash mound is a heap of vitrified cow dung, gathered in one place to be burnt as fuel periodically. Upon chemical analysis, ash mounds were found to be important in reconstructing the environment of the past. Later, between 1997 and 2005, when the site was reworked by Ravi Korisettar and his team, the presence of an ash mound was confirmed at Sannarachammagudda and dated to 1950 BCE (Korisettar 2004; Fuller et al 2007).

At the Sanganakallu complex, investigators studied the early Neolithic phase – mapping the beginnings of domestication and how it gradually spread all over the area. From the Neolithic phase, the occupants of Sanganakallu marched into the Neolithic-Megalithic transition phase, suggesting that the beginning of the Megalithic tradition is in the later stages of the Neolithic period. Here, a large hill called Hiregudda became the manufacturing centre for the ground stone axe. Evidence from the Neolithic and Iron Ages is also noted here.

The study of archaeobotanical (plant) remains at the site by archaeologist and professor Dorian Fuller suggests that people consumed Browntop millet, bristly foxtail, and horsegram, with wheat and barley present from the beginning of the Neolithic period. Investigators attribute this to the dispersal of crops from the Deccan region.

They domesticated goats and sheep along with cattle. Therefore, Sangnakallu, though not the earliest Neolithic site, shows that the continuity of cultures from Neolithic to Megalithic possibly led to the beginning of an important tradition. It also opens doors to new understanding of the diffusion of cultures across peninsular India.

Analysing the southern Neolithic complex at Sanganakallu – and numerous excavated sites across state borders – thus, is important when discussing the newly published dates in the region. Linearity is not visible across the board, and one has to consider many factors before reconstructing the past. When talking about the Iron Age, two important pieces of evidence (besides Iron) are often quoted – Black and Red Ware pottery, and Megaliths. What we see from the decades of work put in by scholars is that both existed in the Pre-Iron Age complex, and that there was a continuity of tradition. However, if we extend the timeline of the Iron Age to the third millennium BCE, we must reconsider Neolithic and Megalithic settlements. Without them, the narrative is incomplete and until we do so, it will remain incomplete.

Disha Ahluwalia is an archaeologist and research fellow at the Indian Council of Historical Research. She tweets @ahluwaliadisha. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)