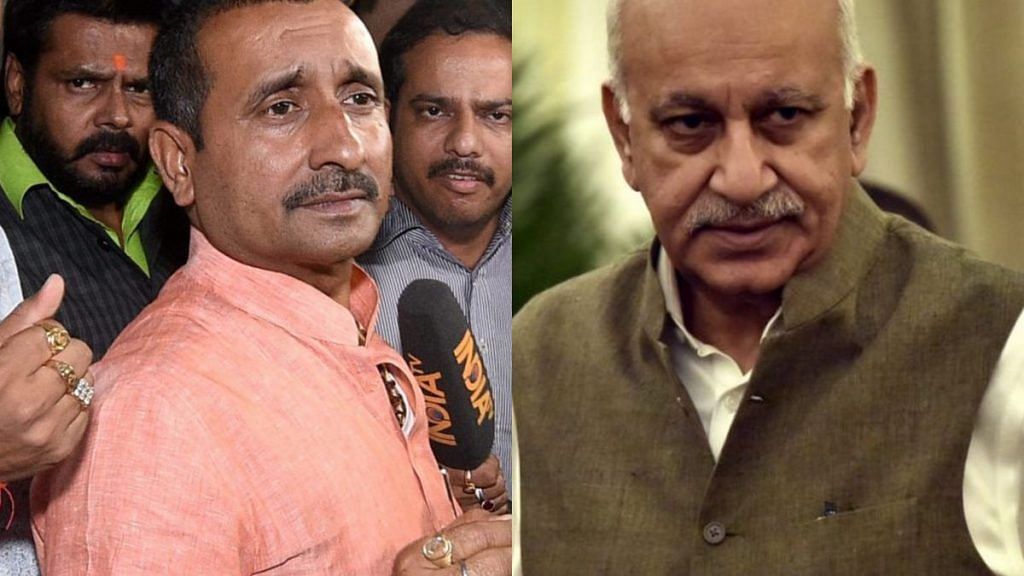

Three developments have happened in high-profile rape trials in the last 10 days. A Delhi court found expelled Uttar Pradesh BJP MLA Kuldeep Singh Sengar guilty of raping a minor girl of Unnao in 2017.

The Bombay High Court directed the trial court hearing the rape case involving journalist Tarun Tejpal to not allow his lawyer to pose “indecent and scandalous” questions to the victim.

And, in the court hearing of former Union minister M.J. Akbar’s defamation case against his former journalist-colleague Priya Ramani saw members of his legal team allegedly laugh while key witness Ghazala Wahab, who was also allegedly sexually harassed by Akbar when he was the editor of The Asian Age, was narrating her ordeal to the court.

Tejpal was booked in November 2013 and the case has been dragging on since then. Trial proceedings in Sengar’s case ended earlier than other conspicuous rape cases — it still took the court way more than the six-month period fixed by the Supreme Court – mainly due to the fact that overt attempts were made to eliminate or influence the victim as well as witnesses, following which even the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) couldn’t do much to protect the powerful politician.

That the trial court indicted the country’s premier investigating agency, CBI, for being unfair to the Unnao victim and her family, only shows how powerful supporters Sengar has. Judge Dharmesh Kumar observed “…It appears that somewhere the investigation in the instant case has not been fair qua victim of crime and her family members. The investigation has not been conducted by a woman officer as mandated by Section 24 of the POCSO Act and successive statements of the victim girl ‘AS’ had been recorded by calling her at the CBI office without bothering for the kind of harassment, anguish and re-victimization that occurs to a victim of sexual assault in such case”.

The cases of Tejpal, Sengar and M.J. Akbar are symptomatic of all that is wrong with India’s criminal justice system, particularly investigations of crimes against women. Akbar’s lawyers, it seems, are going to extreme lengths to drop rape allegations made against him by a former colleague, and turn it into one of defamation.

Also read: SC wants lower courts to speed up rape trials, but 26% judge vacancies make it difficult

Why the Tejpal case is important

Tarun Tejpal’s case has progressed excruciatingly slowly, ever since he was first accused of sexual assault by his junior colleague in November 2013. It took another few months for Goa police to chargesheet him. Six years on, the case lingers on much like the thousands of other ill-fated sexual assault cases in India.

At a time when the #MeToo movement seems to be ebbing, there is a need to bring closure in cases like Tejpal’s.

Instead, we have an unending trial where Tejpal’s lawyers are using an arsenal of legal tricks to prolong the matter. This is when the Supreme Court in August asked the trial court in Goa to conclude the trial within six months, while refusing to quell the rape charge.

The direction given by the Bombay High Court last week came after the woman sought a partition screen because she felt intimidated by Tejpal.

Add to what the special public prosecutor in the case had to say on the issue of victim’s alleged browbeating and you get a fair idea of where things stand.

“The grievance made in the petition is that throughout cross-examination ever since it started nothing relevant to the case have been asked. The questions asked so far have been humiliating and amount to victim shaming. None of the questions are relevant to the case, this is contrary to law, victim has alleged. After so many sessions if the cross-examination questions are still irrelevant to the case, the manner in which it is being conducted, there is no end in sight,” he told Live Law.

Early on in the case, the prosecution had accused Tejpal of “changing colours like a chameleon”.

The controversial two-finger test, which was earlier almost a norm among law enforcement agencies, was outlawed by the Supreme Court in 2013. It’s another case altogether that there have been reports on the continued use of the test.

But, in Tejpal’s case, the two-finger test seems to have been replaced by “indecent and scandalous” questions posed to the victim during cross-questioning.

It is nobody’s case to establish that Tejpal is guilty of the offences that he has been charged with. It is the judiciary’s responsibility to decide the fate of a lawsuit but Tejpal’s case shows how far India is from a scenario where an alleged rape victim can expect a fair and speedy trial without being ashamed or feeling intimidated by the accused.

Also read: No outrage unless Hyderabad, Unnao, Kathua-like rape: UN Resident Coordinator in India

Judiciary’s task

The courts should stick to the basics. Concluding a trial, especially in a high-profile case like the one involving Tejpal, within six months will always be a big ask because the wheels of justice tend to move very slowly. So, what the courts can certainly do is ensure that needless delays are contained.

It is often the accused, often powerful people with ample resources, who are able to delay cases against them. While the due process of law can’t and shouldn’t be denied to anybody, it can’t always be allowed to be tilted in favour of the rich.

Also read: Dear CJI, Indians have lost faith in judiciary because we are ruled by power, not by law

Unless cases, involving those who act high and mighty, are dealt with swiftly, rapes won’t stop in India. As won’t the continued shaming of the victim.

The author is a senior journalist. Views are personal.