Leaving the little office above a mother-and-child store on Dubai’s Crescent Drive, Mohammad Eslami clutched a one-page, handwritten note listing the price of the apocalypse. For prices running from a few million dollars to a few hundred million dollars, German engineer Heinz Mebus and Sri Lankan businessmen Mohamed Farouq and Buhary Syed Ali Tahir were willing to provide uranium-enrichment technology, sample gas centrifuges, and the equipment to manufacture them.

There was even a 15-page technical document provided by their boss, Pakistan’s nuclear weapons czar Abdul Qayyum Khan, explaining how to mill the uranium spheres at the heart of a nuclear bomb.

For over a year, Iranian and United States diplomats have been engaged in negotiations on how to put that nuclear genie back in the bottle.

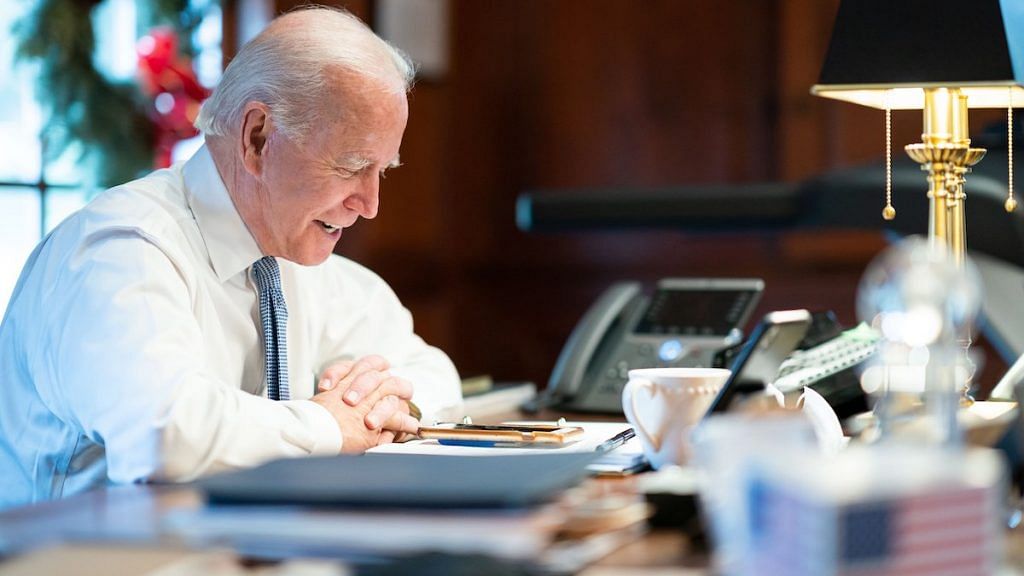

In principle, the deal couldn’t be easier. America needs Iran’s oil and gas to help wean the world off Russian hydrocarbons. Iran needs an end to sanctions that have crippled its economy. Iran, though, won’t sign unless sanctions on its elite Islamic Revolutionary Guards are lifted. And President Joe Biden’s administration doesn’t have the political capital to make that concession.

Earlier this week, Iranian foreign ministry spokesman Saeed Khatibzadeh said the agreement is in “the emergency room.”

Also read: West helped fuel Ukraine crisis by letting the nuclear genie out of its Cold War cage

The Iran nuclear deal backstory

As I have written before, four years ago, former President Donald Trump’s administration unilaterally pulled out of a deal Iran had made in 2015 with the so-called P5+1 group of powers—the five permanent members of the United Nations, which are the United States, China, Russia, the United Kingdom, and France, as well as Germany. Iran, in essence, had agreed to restrictions on its stockpile of highly enriched uranium—the building block for a nuclear weapon—in return for America lifting sanctions imposed in 2006.

Even though the agreement didn’t guarantee Iran would never, in the future, seek nuclear weapons, it significantly enhanced what is known as ‘breakout time’—the period it would take Tehran to build a weapon, after deciding it wanted one. That, most experts believed, was better than the uncertainties of no deal.

To critics like Trump, though, the nuclear agreement had one big hole. Iran wasn’t, notably, compelled to end its research and development of ballistic missiles. Within weeks of the P5+1 agreement, Iran tested the Emad intermediate-range guided missile that can deliver a 1,750 kilogram payload—enough for a nuclear weapon—to targets up to 2,500 kilometres away.

Iran, a second argument used by the critics ran, could evade the international monitoring provisions of the nuclear deal. Israel, notably, had done the same thing—first promising its Dimona plant would never be used to manufacture nuclear weapons and then defeating inspections by bricking-off parts of the facility and providing faked reactor-operations data.

Together with Saudi Arabia, Israel also argued the P5+1 agreement hadn’t addressed a third problem: Iran’s use of proxies, as well as terrorist groups, to pursue its interests across the region. Lifting sanctions, they asserted, would give Tehran the economic muscle it needed to push its regional war aggressively.

To the ire of his P5+1 partners—and, of course, Iran—President Donald Trump’s administration listened to the critics, and withdrew from the agreement in 2018.

Even though Trump’s sanctions on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) are of little substance—especially since separate ones would remain in place even if the nuclear deal goes through—the political equities for both sides are large. President Biden would expose himself to domestic criticism from powerful politicians and lobbies sympathetic to Israel, should he lift the IRGC sanctions. Iranian hawks, similarly, won’t allow a deal that keeps the sanctions in place.

Also read: What’s behind India’s Ukraine policy, Western hypocrisy & how nations act in self-interest

The long shadow of suspicion

The problem boils down to trust. The relationship between the United States and Iran fractured in 1979, when revolutionary Islamists took diplomats hostage at the United States embassy in Tehran. The United States saw the revolution as a fundamental threat to the post-Second World War order it had built in the Persian Gulf, centred around protecting access to the region’s oil. The United States backed Iraq’s war on Iran from 1980; Iran, in turn, struck at United States targets in the region through proxies like Hizbollah, notably bombing a Marine barracks in Beirut in 1983.

Following 9/11, signs of new pragmatism emerged from Tehran, as I noted before. Iran provided intelligence on the Taliban and al-Qaeda to the United States and, in 2003, conveyed conditions for peace talks, through Swiss diplomats. “The Bush administration, full of hubris after the quick overthrow of the Taliban and Saddam, didn’t respond,” expert Barbara Slavin has recorded.

Instead, Washington gambled on its coercive options, believing it could overthrow the Ayatollahs. In 2002, then-President George W Bush had branded Iran part of an “Axis of Evil” that had to be overthrown. Tehran concluded that, like Saddam Husain’s Iraq, it would also be targeted for regime change.

To protect itself, Iran-backed Shia insurgents in Iraq, who staged hundreds of attacks on American troops, tying them down in an unwinnable urban war. In addition, Iran allowed al-Qaeda jihadists to transit to Syria, and began supplying weapons to the Taliban in Afghanistan.

In the so-called Arab Spring of the 2010s, Iran expanded its regional influence. It backed President Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria, and undermined Saudi Arabia’s efforts to control Yemen. Hezbollah, Iran’s Lebanon-based client, also received enhanced support.

The P5+1 nuclear agreement could, in addition to tamping down Iran’s nuclear ambitions, however, address the mistrust between the region’s powers—and was eventually blown apart by them.

Also read: India shouldn’t fall for Putin’s rupees-for-rubles deal despite tempting discount on oil

The fraught path forward

Few think the breakdown of the P5+1 agreement has made the region more secure. For one, Iran’s breakout time has diminished. In response to Trump’s decision to walk out of the agreement, Iran began enriching uranium to 60 per cent purity, far higher than the grade needed for generating power for research activities. Israeli experts claim Iran is just 24 months away from being able to field a nuclear-weapons arsenal—a plausible contention.

The larger problem is the deal isn’t just about nuclear weapons. Tehran and Washington need to agree on the role and influence of Iran in the region—and then get states like Israel and Saudi Arabia to sign on to it.

Lessons learned by both sides could provide a bedrock for agreement. Iran desperately needs access to Western markets if its moribund economy is to revive. In spite of its close relationship with China, Tehran has learned the partnership isn’t a substitute for genuine reintegration in the global economy.

According to the China Global Investment Tracker, China’s invested $26.5 billion in Iran from 2010 to 2020. In the same period, China invested $43.7 billion in Saudi Arabia and $36.16 billion in the UAE. Iran might have been forced to look east, expert William Figuera has noted, but China is looking in many directions.

For its part, Washington has also learned that coercion has limits. Long-running sanctions debilitated North Korea, but did not tip over its regime or impede its nuclear-weapons and missile programmes. Iran’s theocratic regime, likewise, remains intact in spite of years of sanctions. The United States’ policies haven’t made the Persian Gulf more secure.

The two sides have, over decades, rarely missed a chance to miss a chance. The world will face a sharp bill should they fail, again.

Praveen Swami is National Security Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.