Five Generals, resplendent in their full ceremonial dress, sat at the table, glowering at the war hero before them. Five years earlier, in 1971, Major-General Tajammul Husain had held off superior Indian forces at Hilli, in East Pakistan. Then, denied promotion, General Husain decided to turn his guns on the inquisitors who had now gathered to judge him: Army chief Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, Zia’s spymaster, Lieutenant-General Ghulam Jilani, and Lieutenants-General Sarwar Khan, Faiz Chishti, and Gul Hassan.

Less than a week later, Tajammul was thrown out of the army. Letters were sent out to garrisons across the country, Tajammul wrote in his memoirs, letting troops know he had been plotting to overthrow Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s government and replace it with an Islamic State.

“Fanatic,” Zia growled: He was, perhaps unaware he himself would hang the Prime Minister, and begin serving the will of God with public amputations and floggings.

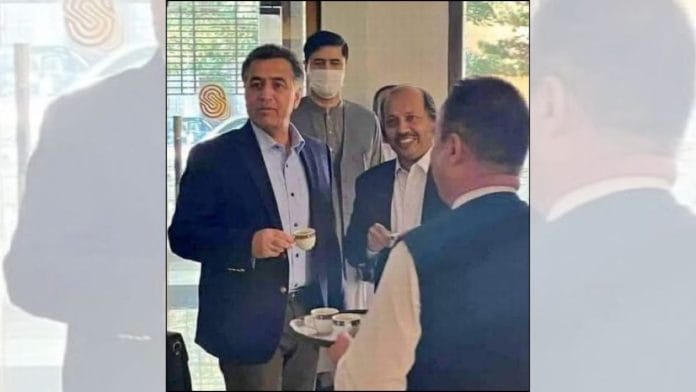

The arrest and coming court-martial of former ISI chief Lieutenant-General Faiz Hameed, announced this week, is intended to crush former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s supporters inside the military. Two officers active in Imran’s support, Major Adil Farooq Raja and Captain Haider Raza Mehdi, have already been handed down sentences. Figures like Khadijah Shah, granddaughter to former Army chief Asif Nawaz Janjua, have spent months in jail.

Tajammul’s failed coup reminds us that elements within the military have repeatedly sought to overthrow the state and their own commanders. Losing lives every week in an unwinnable war in the country’s north-west, the economic lives of their families and kin in ruins, and the unchecked power of a corrupt élite, the rank-and-file is showing signs of deep alienation, eminent scholar Ayesha Siddiqa notes.

Faiz’s trial is meant to serve as a demonstration of Army Chief General Asim Munir’s complete authority—but it could only too easily prove a dangerous gamble.

Also read: Sheikh Hasina’s fall will lead to rise of the only organised force in Bangladesh—religion

Turning mud into gold

Like so much else to do with the Pakistan Army’s power struggles, the story of Faiz’s downfall has to do with mud—which the military has learned how to transform into gold through the dark arts. In 2004, journalist Marvi Sirmed reported, that property magnate Iftikhar Ali Waqar, together with his sister Zahida Aslam, put up the cash to build the Top City housing project in Rawalpindi. Zahida and Iftikhar soon fell out, though, and the brother ended up dying of suicide. For all practical purposes, control of the project ended up with her manager, Kunwar Moiz.

In 2014, Moiz found himself called on to aid the campaign of Tahir-ul-Qadri, a military-backed cleric who played a key role in destabilising then-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s government. He also became involved with Haider Abbas Rizvi, a Mohajir Qaumi Movement leader acting as a mediator between the government, military and Imran.

Likely, Moiz’s political contacts greased Top City’s wheels from the outset. The Auditor General of Pakistan discovered organised wrongdoing to aid its profitability. Land sold for the project, among other things, had been undervalued; permission had been given to build shops in residential buildings, and apartment blocks sanctioned in excess of the land-usage regulations.

The ties to the MQM were adroitly used by Moiz’s business rivals, to seize a share of the project. In 2017, allegedly on Faiz’s orders, personnel from the ISI and the Pakistan Rangers raided Top City’s offices and confiscated jewellery and cash from Moiz’s home. According to the businessman, he was only released from illegal custody when he handed over a part of his properties to nominees of Najaf Hameed, Faiz Hameed’s brother and a low-level bureaucrat.

Faiz isn’t the only one of Imran’s military commanders to face corruption allegations. General Qamar Javed Bajwa, the former Army chief and Faiz’s one-time boss, has been accused of accumulating an estimated $56 million in property through his six years in office.

Though some of that came from land entitlements top Pakistani military officers are entitled to for their service, his relative and retainer Sabir ‘Mithu’ Hameed is accused of coercing landowners to sell land in areas where major projects were to be developed. Hameed is now being investigated by the Federal Investigation Agency on money-laundering charges, which could lead them to General Bajwa.

Also read: Pakistan has laid a trap for itself in Gwadar — by letting conspiracy theories dictate policy

A cage for Imran?

For months now, General Asim’s frustration at not being able to crush Imran has been evident. Imran and his wife, Bushra Bibi, have succeeded in gaining bail in a series of graft cases; efforts to prosecute them for violating religious laws governing marriage also collapsed. To make things worse, the Supreme Court ordered that Imran’s Tehreek-e-Insaaf party be given a share of reserved seats in the legislature, enhancing its political presence. Last week, Bilawal Bhutto, the head of the Pakistan People’s Party, bitterly complained of pro-Imran judicial bias.

There’s little doubt efforts have been made to bulldoze that supposed bias. In March, six judges of the Islamabad High Court complained that the ISI had used kidnapping, torture, and secret video surveillance in an effort to secure their compliance in cases against Imran. Even these crude tactics, however, didn’t succeed in making the judiciary prisoners of war.

Faiz’s prosecution potentially offers a means to prosecute Imran before a military court—but it’s far from clear how the increasingly assertive civilian court system might treat such a development. The Supreme Court had, last year, stopped the trial of Imran supporters, alleged to have been involved in violence after his arrest, in military courts.

Even if he fails to draw Imran into the military justice system, though, General Asim could benefit by projecting himself as a crusader against corruption. Endemic corruption in the officer corps has caused deep resentment in the ranks, but action has been rare.

Lieutenant-General Obaidullah Khattak, the former inspector-general of arms, and Major-General Ejaz Shahid were dismissed from service in 2016 after a court of inquiry, on the charge of misappropriating funds during their tenures within Balochistan. There were, however, no prison sentences handed down.

The Pakistan National Assembly had earlier indicted Lieutenant-General Javed Ashraf Qazi, a former spymaster who went on to become railway minister, on corruption charges. Together with Lieutenant-General Saeed-uz-Zafar, General Qazi was accused of handing over railway land to a Malaysian conglomerate without proper diligence. The case is still underway.

Also read: With Faiz Hameed’s arrest, Pakistan Army has punished one of their own. It’s a warning

The coups within

Too much pressure against Imran, though, could end up opening deep fault lines of class and ideology inside the armed forces. Following early meetings with the Islamist politician Abul A’la Maududi, the village-born Tajammul rejected the colonial heritage of the armed forces. “To become a good officer, one was expected to drink, dance and even speak the Urdu language with English accent,” he recounted. “The sooner one adjusted oneself to complete European way of life, the better one’s chances were to be regarded as a good officer.”

“Anyone who talked about religion was considered to be a backward type and sometimes even ridiculed in public,” Tajammul complained.

Following his first coup attempt in 1976, Tajammul again planned to install an Islamic government by assassinating Zia at the Pakistan Day parade in 1980, scholar Shuja Nawaz records. Islamist coup plots like these have been common. Led by Brigadier FB Ali, officers sought to overthrow the government in 1972–1973, believing the Government’s un-Islamic ways, and General Yahya Khan’s drinking had led to the loss of Bangladesh.

Then, in 1995, a group of 40 officers led by General Zahirul Islam Abbasi, Brigadier Mustansar Billa and Colonel Azad Minhas plotted to assassinate Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, as well as the senior leadership of the army. The Army, Nawaz writes, “refused to face the reality that the army officer corps was increasingly coming from urban centres where there was a strong Islamist current, and that the army’s own population, after all, mirrored the increasingly conservative bent of the country’s general population.”

Like his predecessors, General Asim confronts the millenarian impulses represented by Imran Khan: To his ranks of supporters, the former Prime Minister represents at least an illusion of an equitable, just Pakistan, free from corrupt military officers and predatory politicians. Lacking any political strategy for comprehensive economic and social reform, General Asim is seeking to break his opponents at the wheel—but it is far from clear if he can succeed.

Praveen Swami is a contributing editor at ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)