Versailles in the jungle” is what President Mobutu Sese Seko called his palace in the mud-and-straw village of Gbadolite in Congo, complete with Carrara marble terraces, art, sculptures, two swimming pools and ersatz Louis IV furniture. “Liveried waiters served roast quail on Limoges china and poured Loire Valley wines, properly chilled against the equatorial heat,” a reporter recalled. The chef was flown into the village on a chartered supersonic Concorde, landing on a purpose-built three-kilometre runway.

In a sermon at Kinshasa’s football stadium in the summer of 1976, Mobutu made this generous offer to his people: “If you want to steal, steal a little in a nice way.” The president re-instituted the right to ‘deflower’ virgins, once exercised by tribal chiefs. For a time, his education minister considered replacing icons of Jesus with those of the messiah in the leopard-skin hat.

Then, three decades after he seized power, the world turned—and Mobutu was forced into exile, where he would die of cancer.

Ever since the Pakistan Army staged its first successful coup d’état in 1958, and became the country’s most important institution, it has operated with the certain knowledge that the house never loses. Like Mobutu, the Generals have granted themselves gargantuan estates, captured corporate empires and engaged in excesses that rival those of the Roman emperor Caligula. The thing is, the house does sometimes lose—hollowed out by traitors or the merely incompetent, or simply because of the fickleness of the goddess of fortune.

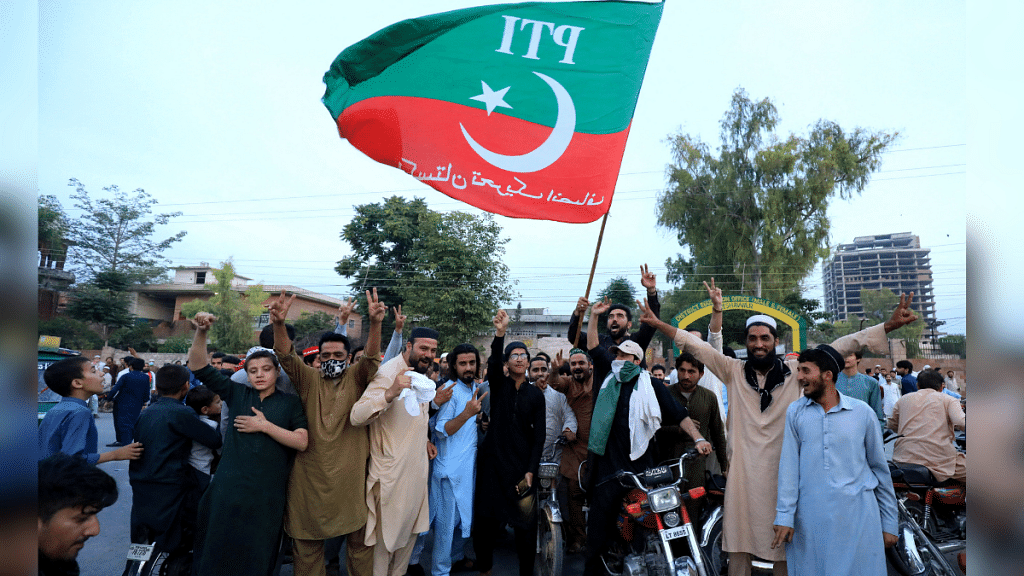

Last week’s attacks by mobs of former prime minister Imran Khan’s supporters on the homes of top Pakistani officials—and the frontal confrontation between army chief Asim Munir and the former prime minister—many are beginning to wonder if the military can remain the hegemon that guides the nation’s fate.

Also Read: Pakistan is imploding. A failing neighbour will be a nightmare for India and the world

The cracks in the steel phalanx

Even if images of rioters stealing peacocks and frozen strawberries from Lahore corps commander Lieutenant-General Fayyaz Ghani’s home might seem to belong in the realm of the darkly amusing, rather than catastrophic, many experts see them as symptoms of a wider breakdown within the steel phalanx. Lieutenant-General Fayyaz is reported—though not officially confirmed—to have been relieved of his command, in what is being interpreted as a cautious purge against supporters of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) inside the army.

Leaked audio messages from one of Lieutenant-General Fayyaz’s relatives suggest the family escaped from their burning mansion—once owned by Pakistan’s founding patriarch Muhammad Ali Jinnah—into a house owned by a relative of chief justice Umar Ata Bandial. The audio message, obtained by ThePrint, suggests Lieutenant-General Fayyaz was opposed to the army chief’s policy of confrontation with PTI chief Imran Khan.

Three important commanders—Lieutenant-General Asif Ghafoor, Lieutenant-General Saqib Mehmood, and Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee chair General Sahir Shamshad Mirza—are also believed to have cautioned General Asim against a showdown, arguing that pitting ethnic-Punjabi and ethnic-Pashtun soldiers against the population could have terrifying consequences. The Pakistan Army has struggled to contain jihadist influence among its ranks ever since 9/11, and involving the military in civil conflict could accelerate the process.

Families of serving army officers were seen joining protests against the government, in social media videos, an indication of the political zeitgeist among younger officers. Former military officers like Lieutenant-General Tariq Khan, a hero of Pakistan’s war against jihadists in its north-west, have publicly supported Imran. Lieutenant-General Amjad Shoaib, another supporter of Imran, was arrested on charges of inciting violence.

General Asim has begun the process of appointing hand-picked officers to key positions, promoting Rahat Naseem Khan as Lieutenant-General to lead the National Defence University. Khan replaces, Lieutenant-General Raja Nauman Mehmood, a one-time rival of Asim to lead the army. In September, Asim will have the opportunity to promote several more loyalists to Lieutenant-General, former intelligence officer Rana Banerjee has noted.

The Government hopes Asim can ensure peace through the summer, as key pro-Imran figures leave office at the end of their term—among them, President Arif Alvi, and chief justice Umar Ata Bandial. Then, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif hopes, the Army will be able to ensure Imran’s defeat in elections—just as it helped secure his election.

Even six months ago, there would have been little reason to doubt that this well-tested script would play to plan—but the deep political fissures in the army give reason to question if that will be the case.

Also Read: More than Imran, it’s jihadist influence on Pakistan army that’s Gen Asim Munir’s headache

The politics of the jackboot

Lacking effective party structures and mass legitimacy, historian Maya Tudor has written, politicians in Pakistan struggled from the outset to create a functional polity. Leaders of the Pakistan movement, it has often been noted, had little influence in the new nation. The prospect of ceding their power to elected politicians led the military and administrative leadership, Grażyna Marcinkowska notes, to stage the country’s first coup in 1958. The military would stage successive coups to keep its institutional primacy and financial privileges.

Fractures in political elites led to the consolidation of military-led systems in many parts of the world. Following the establishment of the Turkish Republic in the last century, the Republican People’s Party of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk ruled until 1950. Fear that the Islamist-leaning politics of Prime Minister Adnan Menderes would undo Kemal’s secular legacy led the military to stage the first coup—and execute the politician—in 1961.

Though each subsequent period of military rule in Turkey was short, Brazil plunged into a decades-long military dictatorship in 1964, followed by Chile in 1973. Argentina went the same way in 1976. For decades, dictatorship appeared to be the natural order of things. The economic crisis in the 1980s, and the end of the Cold War, led the United States to withdraw support for dictators, though—leading jackboot regimes to collapse.

Even though Mobutu expanded his military power, doubling the size of the army in his decades in power, the corruption and politicisation of the regime meant it abandoned him at his moment of crisis. Like many other despots, Mobutu feared a unified and professional officer corps could end up deposing him.

The dictator’s problems deepened, scholar Kisangani Emizet observed, after the United States and France withdrew the carte blanche they had extended to the anti-communist Mobutu during the Cold War.

Also Read: The soured love affair between Imran Khan and Pakistan Army is a ticking time bomb

A moment of decision

Even though the mob attacks on Pakistan military institutions and homes are unprecedented, the crisis isn’t. Anti-army slogans have been a part of Pakistan’s street culture since the time of dictator General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq. The scholar Aqil Shah observed that, for all its modernising pretensions, General Pervez Musharraf’s regime had mired Pakistan in an economic crisis and civil war against jihadists.

The Lawyers Movement which deposed General Musharraf, among other things, birthed Imran and the judiciary which has insulated him from assault by General Asim.

Earlier crises have seen the army find successful instruments to overcome these challenges. General Zia’s regime successfully instrumentalised Islam to grow its legitimacy. Following the tarnishing of the military’s image under General Musharraf, the Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate engineered 26/11, rallying the public through a crisis with India.

All power, though, depends on illusion—and the end of despots like Mobutu shows that illusion shatters more easily than we imagine. Imran is taking Pakistan into profoundly unpredictable terrain, likely with consequences that cannot yet be imagined.

The author is National Security Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)