Later—much later—the daughter of the murdered man, and the man who shot him dead, watched their own children play together in the garden outside: “There was loss at both ends,” she remembered. Following a first, unplanned meeting at a Ludhiana coffee shop, their families had come to exchange small gifts—home-grown flowers, a salwar-kameez—and visit each other’s homes. Later, Avantika Maken would write a letter requesting commutation of the life sentence handed down to Ranjit Singh Gill, one of the three assailants involved in the killing of her father, the Congress MP Lalit Maken.

As India prepares for the looming extradition of the 26/11 terror attack accused Tahawwur Rana, that improbable story of desolation and absolution holds special meaning. Four decades on, the assassination of Maken, and the extradition proceedings that followed it, raise painful questions about the ultimate meaning of justice.

The case—the very first successful extradition proceeding brought by India against a terrorism suspect in the West—set up the template for charges of police mishandling of evidence and poor investigation, which have stained many efforts since. There was also the bizarre: Lead American prosecutor Judy Russell checked herself into a psychiatric hospital, after it was discovered she had fabricated death threats purported to have been sent by the men fighting extradition.

Fifteen years would pass between the extradition of Ranjeet Singh Gill, and the day in 1985 when Avantika was sternly told not to cry when the body of her father was brought home.

Khalistan movement & the world

To understand the significance of the Lalit Maken case involves visiting an India whose understanding of the world was shaped by Cold War paranoia. Foreign leaders, among them former German chancellors Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt, were told by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi that the Central Intelligence Agency was fuelling pro-Khalistan violence. Ten days after the Indian Army cleared the Golden Temple of terrorists who had taken it over, intelligence officials claimed the CIA had funnelled weapons through Pakistan to the followers of Sikh separatist leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale.

Even though the idea that the CIA might be seeking to destabilise pro-Soviet Union states wasn’t improbable, American intelligence officials insisted that they were innocent of this particular crime.

George Bush, then-CIA chief and later President of the United States, grumbled in a private letter to the Research & Analysis Wing (R&AW)’s Rameshwar Nath Kao about “Statements by government officials linking CIA operations with occurrences in Amritsar [which] are completely contrary to the fact and quite distressing…this turn of events is particularly unfortunate coming so closely on the heels of my statement in New Delhi respecting the unity and integrity of India and my long discussions with your Prime Minister.”

Following the assassination of Indira Gandhi, and the rise to power of her son Rajiv Gandhi, the United States was keen on growing the opening to the West offered by the new Prime Minister. Pro-Khalistan terrorism soon offered itself as a touchstone for developing trust between the countries.

In 1987, the Government of India sought the extradition of Ranjeet Singh Gill and Sukhminder Singh Sandhu, on separate terrorism-related charges. Sukhminder Singh was alleged to have participated in two bank robberies, in Ahmedabad and Mumbai, as well as an attack on police officers in Udaipur, the kidnapping of another officer in Mumbai, and participation in the murder of former Indian Army chief Arun Shridhar Vaidya.

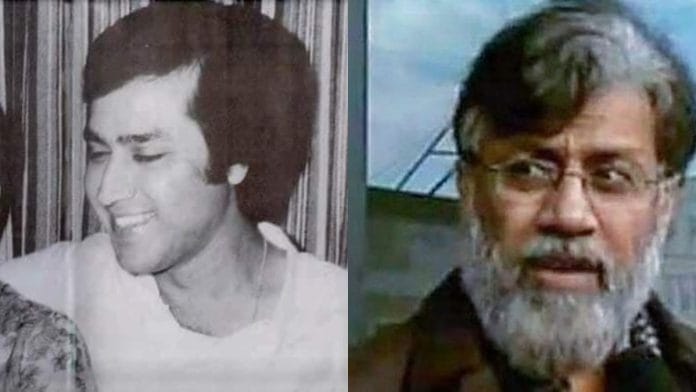

For his part, Gill was accused of participating in the hit team that assassinated Lalit Maken, his wife Geetanjali Maken, and one of the MP’s constituents, Balkishan Khanna. The 31 July 1985 assassination was carried out in retaliation for the anti-Sikh pogrom in Delhi, carried out in the wake of Indira Gandhi’s assassination. The two other assassins involved in the killing, police later discovered, were Sukhwinder Singh, who used the pseudonym KC Sharma, and Sukhdev Singh, later convicted and executed for the murder of General Vaidya.

Fifteen-year-old Muhammad Salam, who worked at the Maken home, would later tell a court the three men had loitered outside the house, saying they wanted to see the MP for help securing a bank loan. In the minutes before the shooting began, they even helped Geetanjali Maken sort through mangoes she was buying from a passing vendor, sorting through the best ones.

Even though he fled India on a fake passport identifying him as Yashpal Kashyap, Ranjeet Singh was located by Interpol, and arrested by police in New Jersey in 1987. The story, however, wasn’t quite done.

Also read:

The question of truth

Like now, the idea that the US and the West were wilfully shielding terrorists, as part of a conspiracy against India, was deeply embedded in popular culture and discourse. Through the Cold War, politicians such as Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru stoked these suspicions. To extradite suspects from the US, though, needed evidence that could stand up to a century of law mandating that “extradition without an unbiased hearing before an independent judiciary … [is] highly dangerous to liberty.”

The court of magistrate Ronald Hedges, law scholar Lauren Wolfe has written, heard evidence from the two men’s lawyers that police in Punjab was engaging in torture, and in the extrajudicial execution of Sikh men. An affidavit in support of these allegations—widely reported in India’s own media—was submitted by Ajit Singh Bains, a judge of the Punjab and Haryana High Court who turned pro-Khalistan activist.

Even though the US was a signatory to international conventions against torture, Hedges reasoned, established law in the US empowered the executive, not the judiciary, to determine if extradited individuals might be subjected to mistreatment. As late as 2008, US courts refused to act against the extradition of two American citizens challenging their proposed surrender to the Iraqi government because of this principle, called non-inquiry.

The problem was, in fact, the Indian courts. In the summer of 1988, the special court judge hearing the Vaidya assassination case, VL Ruikar, cast serious doubt on the confession obtained from key suspect Sukhdev Singh, among the pillars on which the extradition proceedings rested.

Among other things, Judge Ruikar noted that Sukhdev Singh was held in police custody, rather than magisterial custody, before and after giving his confession; the magistrate did not question Singh about his motives for confessing, nor inspected him for physical signs of torture, and the confession was not given in open court.

To make things worse, Ruikar’s judgment noted, evidence surfaced that the Antop Hill kidnapping never took place. A handwriting expert who identified one document as having been written by Sukhdev Singh identified the same text as also authored by Sukhminder Singh.

Late in 1990, a New York district court granted Ranjeet Gill and Sukhminder Sandhu the protection of habeas corpus, giving India the right to refile fresh extradition requests.

Also read:

The return home

Ten years later, in 2000, tired of endless legal battles and time in prison, Ranjeet Gill agreed to be extradited to India. The Delhi High Court bench of Justices Mukul Mudgal and PK Bhasin finally upheld his conviction, although serious questions lingered. Four eyewitnesses who were present at the time Ranjeet Gill was alleged to have fired at Lalit Maken, declined to identify him. And even though Muhammad Salam held by his story, some wondered if was really possible for him to be certain whether the middle-aged Sikh in court was the same clean-shaven man he had briefly seen helping Geetanjali Maken buy mangoes.

For decades now, the questions over the integrity of India’s criminal justice system—as well as the use of torture and planted evidence by police—have hung over Indian extradition requests in the West, just as they did in 1987. To address these questions would be not a concession to the West, but a step toward giving Indian citizens the courts and police they deserve. Too many real criminals—terrorists, murderers, economic offenders—have profited from India’s failures for the issue to be allowed to remain hanging.

These questions are certain to rise again, as Tahawwur Rana’s trial proceeds. The Canadian-Pakistani businessman’s lawyers argued, during his trial in Chicago, that the main evidence against him came from a man even more directly involved in the 26/11 attacks, David Headley. Headley’s long, shadowy history as a Drug Enforcement Agency informant, and his record of cutting deals with prosecutors to avoid punishment, make him a potentially toxic witness.

Following their first meeting in Ludhiana, Ranjeet Gill provided Avantika Maken with insight into his radicalisation by the tragic events of 1984. The son of Khem Singh Gill, who won a Padma Bhushan in 1992 for his contributions to plant genetics, Ranjeet Singh Gill had been studying for a PhD when he joined the plot to assassinate Maken, hoping to avenge the hundreds he believed her father had massacred.

There may never be such a moment of acknowledgement and amends for those slain on 26/11. The real perpetrators remain out of reach in Pakistan. Those like Headley, who are in prison, have expressed little genuine contrition to the victims of their actions. There can be no justice, the story of Avantika Maken and Ranjeet Gill teaches us, until there is truth.

Praveen Swami is contributing editor at ThePrint. His X handle is @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)