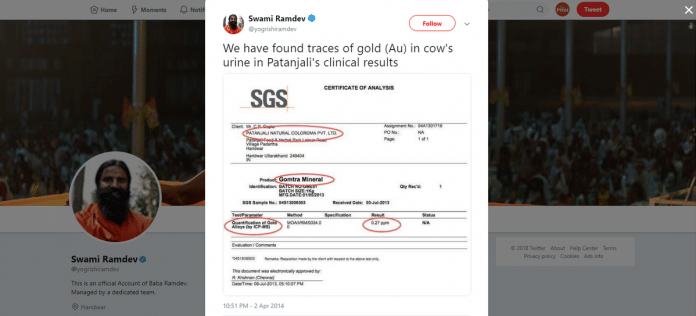

Even as scientists around the world struggle to come up with a vaccine for the coronavirus, Ramdev’s Patanjali Ayurveda announced this week that it has developed a ‘cure’ for Covid-19. According to Ramdev, ‘Coronil and Swasari’ medicine has shown promising results and ‘cured’ all coronavirus patients not on ventilator support who were part of the trial.

The introduction of a ‘cure’ and the resulting reaction — the Narendra Modi government’s AYUSH Ministry has asked Patanjali to stop advertising Coronil, and the Uttarakhand Ayurveda Department has said the company did not mention ‘coronavirus’ in its application seeking licence — raises an important debate on information disorder on social media platforms. And the question of what medical misinformation constitutes during times of a pandemic and otherwise.

Dealing with information disorder

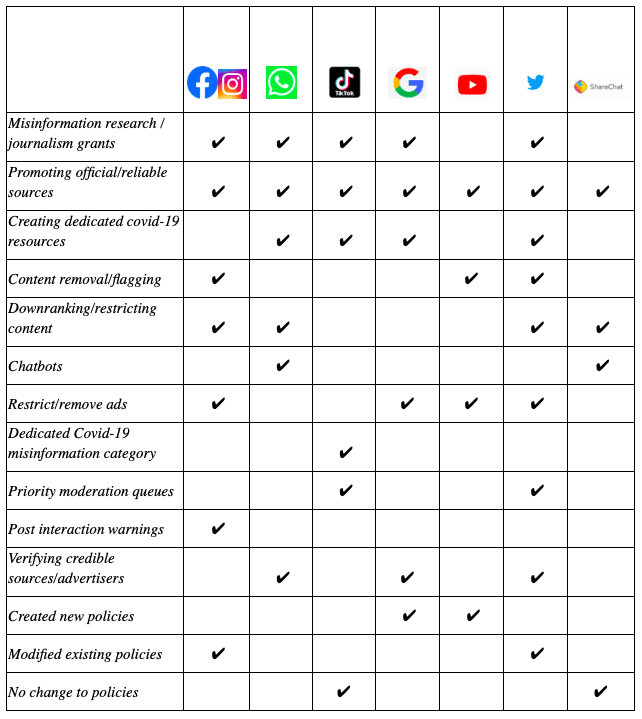

Social media platforms are still in flux when dealing with information disorder and this is why Coronil comes at a very interesting time. Earlier this month, we worked on a paper that analysed platform responses to information disorder and we determined that all responses can broadly be classified into four categories:

- Allocating funds: Platforms have allocated grants to various institutions to support their efforts to manage information disorder. This involves grants to fact-checking organisations, media outlets, and sources of credible journalism. For example, Google is providing $6.5 million to fight misinformation around the world while Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has pledged to provide the World Health Organization (WHO) with as many free ad credits as they need.

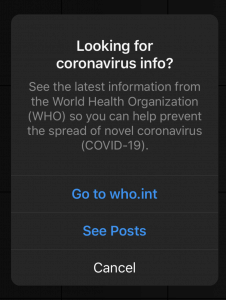

- Changes to user interface (UI): Platforms with a feed or search results as part of their UI are highlighting information from credible public health authorities. This also involves modifying how ‘Explore’ sections function or how search results related to Covid-19 are structured. For instance, Google searches related to the coronavirus now trigger an SOS alert that brings up a dashboard of credible information.

- Changes to information flows: This involves downranking content on news feeds, restricting or removing ads, providing public health authorities with verified chatbots, installing priority content moderation queues, and notifying users about their interactions with misinformation. For example, Instagram claimed it will down-rank content that third-party fact-checkers have rated false, and remove false claims and conspiracy theories highlighted as false by leading global health organisations.

- Policy changes: Platform responses on the policy front have been uneven. Most of them either created new Covid-19 specific policies or modified their existing policies. Some of them chose not to make any specific changes but continued to apply existing policies as they were.

In this regard, responses of social media platforms have varied across the spectrum (indicated in the table below). And given that information disorder related to the coronavirus will continue to evolve with time, these policies are likely to remain in a state of flux.

Also read: Twitter removes over 32,000 propaganda accounts tied to Russia, China, Turkey

User interaction with information disorder

It is this state of uncertainty that provides time and space for information to spread across various platforms. In the context of a ‘cure’ for Covid-19, there can be two modes of driving interactions with such content – advertising and engagement. Most platforms already have policies in place to prevent ads containing misinformation about coronavirus cures. And from an Indian perspective, such ads don’t necessarily lead to a high level of interactions.

The latter category of engagement is important to consider though. This includes both organic as well as artificial interactions (coordinated posts to make a topic trend, etc). Very often the lines that separate them are blurred. Even as the Modi government has asked Patanjali to stop advertising Coronil as a cure for Covid-19, a preliminary analysis of platforms indicated that in spite of intending to direct users to official sources of information, little action had been taken in terms of preventing misleading hashtags from trending, or flagging/removing health misinformation. And in the instances where any action was taken, it was unclear under which policies this happened, or if it was just a response to users reporting the content.

Also read: Now, Twitter will prompt some users to read before retweeting to stop misinformation

How platforms responded to Coronil

A comparison of interactions using the terms ‘coronavirus and ‘Coronil’ are included for reference:

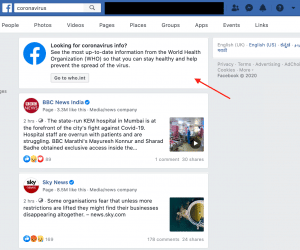

No coronavirus information suggestion. No posts appeared to be flagged at the time of writing.

Instagram

Instagram

No prompt to surface reliable information. No posts appeared to be flagged at the time of writing.

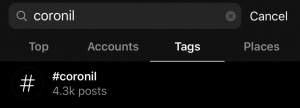

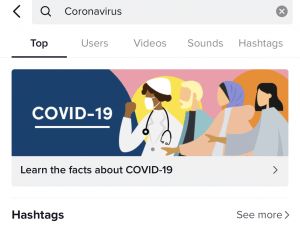

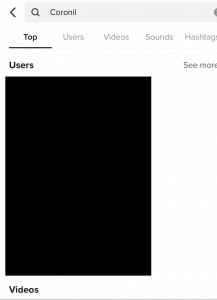

TikTok

TikTok

No prompt for ‘Learn the facts’ section.

Individual posts did not point to Covid-19 related information either.

Individual posts did not point to Covid-19 related information either.

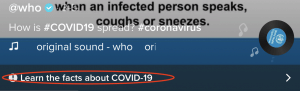

Twitter

Twitter

No prompt for ‘Know the facts’ feature.

Some posts were removed, but it was unclear under which policy the action was taken. It is probable that this was the result of user reporting.

Some posts were removed, but it was unclear under which policy the action was taken. It is probable that this was the result of user reporting.

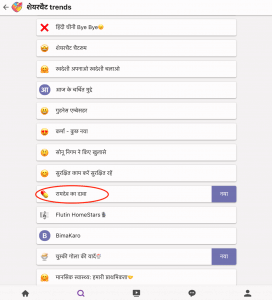

Sharechat

Sharechat

A ‘cure’ related topic was trending, even though the stated goal was to avoid that.

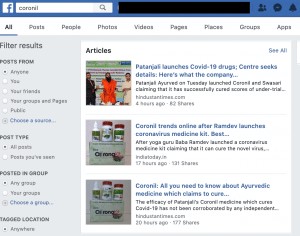

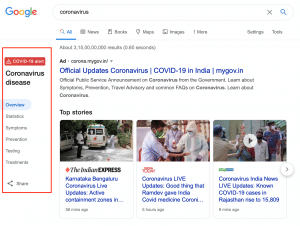

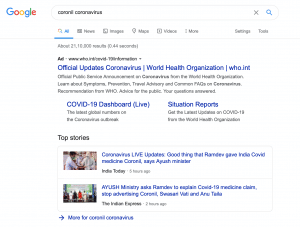

Google

Google

Covid-19 information bar was not displayed.

YouTube

YouTube

Covid-19 information section was not shown above search results.

Also read: Through Covid, tech giants Google, Facebook, IBM now want to win back public trust

Challenges are manifold

Even if they do apply their actions to specific hashtags, the problem does not go away. Associated references/trends — such as Baba Ramdev/Patanjali/Ayurveda, etc. — will surface the same type of content to users. The scenario is representative of the challenges platforms can face when trying to contain misinformation or disinformation. It is further exacerbated when combined with operating across hundreds of countries, multiple languages and diverse local contexts – and platforms’ own tendencies to focus more on North America and Western Europe.

Can platforms take action in all such situations? Should they? Why don’t governments regulate them? Is it more effective for platforms to work alone or together? These are important questions to raise. As we ask social media platforms to intervene more, we also let them assume the role of being ‘arbiters of truth’ and give them even more control. Alternatively, over-regulation of platforms by governments will have far-reaching effects on speech and expression.

As platforms intervene more to address one category of information disorder, this behaviour will leak into other spheres either voluntarily or in response to pressure. If platforms act disparately, there will be plenty of gaps for information disorder agents to exploit. But if they work too well in unison, we could find ourselves at the mercy of ‘content cartels’. How we proceed from here, including in terms of methods adopted against Ramdev’s Coronil, will impact the relationship between states, platforms, and society.

Rohan Seth and Prateek Waghre are Policy Analysts at The Takshashila Institution. Views are personal.

If it was from the west, no one would have said a word !!!

If you see a baba, see saffron or hear that it has something traditional, you won’t say a word.

In the whole field of virology, what percentage of work was done by people not from or in the west? Why would you not place more trust in the west? Trust is based on achievements.

All that people like you are good for is to live in denial.

Very well writren