When European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen attended India’s 77th Republic Day celebrations this year, it was not her being a chief guest but rather her outfit that made the headlines and for all the right reasons. Draped in a rich Banarasi silk brocade Bandhgala with zari work — threads of gold woven into the maroon showcasing Indian floral motifs, designed by Rajesh Pratap Singh, von der Leyen struck a rare diplomatic fashion balance: respectful, restrained, and rooted.

It was a nod to Indian craftsmanship without turning into a cultural performance.

The reaction was telling. Social media applauded her elegance. Fashion critics praised the subtlety. And Indians, notoriously exacting about how their culture is represented, broadly approved. This was cultural appreciation done right.

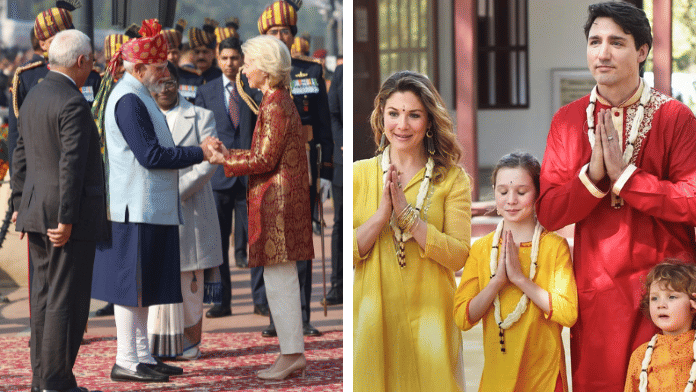

The moment inevitably revived memories of another high-profile diplomatic visit that went in the opposite direction, Justin Trudeau’s en famille 2018 state visit to India, which became synonymous not with policy or partnership, but with spectacle. With him, his now estranged wife Sophie Grégoire Trudeau and their three children embraced Indian ethnic wear with relentless enthusiasm. What might have begun as a respectful engagement soon felt excessive, even theatrical.

Over the course of the week-long trip, they appeared in a succession of Indian outfits or rather “costumes”, especially Sophie. Her anarkalis, sarees, shararas, and brightly coloured kurta sets. One of the most talked-about looks was her yellow Anita Dongre suit, worn when visiting the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad; a flowing, heavily embroidered ensemble more suited to a haldi than a diplomatic visit.

At the Taj Mahal, she chose a floral blue satin dress, part of a larger narrative of hyper-styling. At a dinner in Mumbai with Bollywood celebrities, Sophie Trudeau appeared in an ornate ivory saree while Trudeau himself wore a sherwani, an image that quickly went viral, attracting comparisons to costume drama. Their children, too, wore traditional Indian outfits, with their daughter in a sparkly yellow lehenga and their elder son in a blue sherwani similar to his fathers. The family’s choices altogether were out of place except perhaps at a wedding. However, it is worth noting that most of the other attendees chose to dress simply in sports coats and dresses; a picture of the Trudeaus with Shah Rukh Khan shows the actor in a chic black blazer.

None of these outfits were inappropriate. Many were stunning. And yet, collectively, they created a sense of visual overload, of trying too hard to “perform Indianness.” What might have been intended as respect began to feel curated, calculated, and self-conscious.

Where von der Leyen’s sleek Achkan-inspired jacket is reminiscent of the classic designs one can see among the sherwanis made by luxury male ethic fashion house, Manyavar, the Trudeaus outfits, although designer, looked more like pieces from Delhi’s infamous Palika Bazaar.

This is where the line between cultural appreciation and cultural performance becomes visible. Appreciation is subtle, it signals understanding. Performance, by contrast, seeks visibility, it wants to be seen, photographed, and remembered. The Trudeaus wardrobe choices, taken together, seemed aimed more at spectacle than symbolism.

Also Read: India-Pakistan ready for lehenga diplomacy. Maryam Sharif has made the first move

Walking the tightrope of fashion and diplomacy

Fashion, especially in diplomacy, is not merely aesthetic. It is a political language. Leaders and their spouses are acutely aware that clothing choices carry meaning. They reflect power dynamics, cultural sensitivity, and political intent. Perhaps this is why Michelle Obama, during her India visit, largely stuck to tailored Western silhouettes, occasionally incorporating Indian textiles or motifs, but never fully stepping into ethnic dressing. Princess of Wales Kate Middleton followed a similar approach, favouring Western cuts in Indian colours or embroidery. Who can forget her beautiful Naeem Khan white dress with blue motifs, which she wore to the Taj Mahal. Queen Mathilde of Belgium, too, opted for dresses and subtle integration over performance during her visit to India in 2017. Their choices reflected a diplomatic understanding: when you visit another culture, your clothes should acknowledge, not inhabit it.

Ursula von der Leyen’s Republic Day outfit exemplified this principle. Her Bandhgala retained the structure of European formalwear while integrating Indian brocade, an unmistakable symbol of India’s textile heritage. The garment spoke of partnership, not performance. It suggested respect, not reenactment. She did not attempt to become Indian; she chose instead to honour Indian craftsmanship within her own sartorial vocabulary. Inspired by the Achkan, worn traditionally by nobility for high-level diplomatic appearances, the jacket was a beautiful nod to Indian culture and heritage.

Contrast this with Sophie’s layered looks, each one beautiful, yet collectively overwhelming. The repetition of Indian silhouettes across multiple high-profile appearances made the gesture feel less organic and more choreographed. The effect wasn’t offensive. But it was, unmistakably, on the nose.

That distinction matters.

Because appropriation is not always about offence. Sometimes, it is about excess, about intent that overwhelms context, and about performance that eclipses meaning.

What a lot of people fail to understand is that there’s a lot more to Indian fashion than bright colours and elaborate embellishments, and many may be surprised to learn that a minimalist aesthetic coexists peacefully in the country right alongside sparkly Bollywood-esque glamour, something von der Leyen and some of our past guests understood.

In the Trudeaus’ case, the spectacle distracted from the diplomatic agenda, and headlines fixated on clothes rather than conversations. The visuals overshadowed policy, turning a strategic bilateral visit into a social media fashion carnival. Even within India, reactions ranged from amusement to mild discomfort, not because the outfits were disrespectful, but because they were relentless.

Von der Leyen’s look, by contrast, enhanced the moment. It added symbolism without stealing attention and honoured tradition without turning it into theatre.

In a world where optics increasingly dominate diplomacy, her wearing a beautiful Banarsi brocade sherwani-style jacket felt more like an ode to India’s handwoven textiles and less like a charade to impress the people. Sometimes, less really is more.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Insha Jalil Waziri)