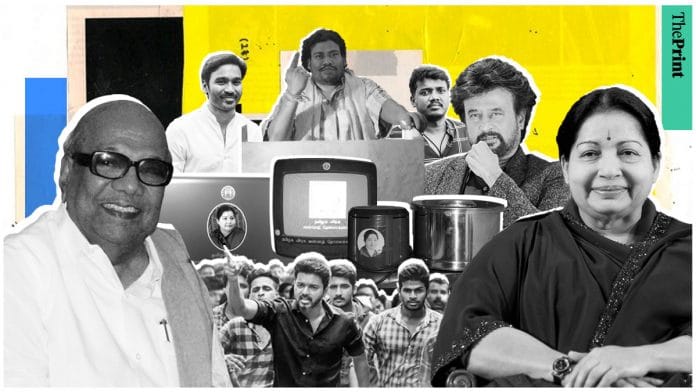

Tamil cinema has always been expressive and vocal about events in state politics. After all, it is quite natural for the state where politics and cinema are closely intertwined and write each other’s scripts. When conversations around ‘freebies’ and ‘freebie culture’are picking up in all places, it is important to note that Tamil films have never shied away from giving strong opinions on the subject.

One of the earliest on-screen critics of Tamil Nadu’s welfare schemes was none other than ‘Superstar’ Rajinikanth. In his 1993 film Valli, also written by him, he approaches a pandal where the state government is distributing sarees and veshtis (dhoti) for men and women. Rajinikanth, who walks in between the crowd with a shawl around his neck, looks at everybody and says, “Are we beggars to ask for sarees and dhotis? Ask for employment.” The Tamil Nadu government continues the tradition of giving sarees and dhotis to ration card holders on the occasion of Pongal under the Priceless Saree and Dhoti Distribution Scheme.

In a scene from Vetrimaran’s 2018 film Vada Chennai, which is set in Chennai of the 1980s and ’90s, Dhanush and Aishwarya Rajesh go to a big house that has a TV set. There, along with a dozen children, they sit and watch a movie. This was the exact case in Tamil Nadu between the 1970s and 1990s. Only a few land-owning, ‘upper caste’households had television sets and people would refer to them as ‘Periya veedu’ (big house).

People who worked as labourers in their farms and mills would stand outside these houses with their children, next to the entrance or behind the window, to catch a glimpse of their favourite TV show or movie. This, of course, happened with ‘permission’ of the owner. Former chief minister M. Karunanidhi, after promising free TV sets in the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK)’s 2006 election manifesto, delivered on this promise after forming the government. TV sets were distributed to people across Tamil Nadu on a massive scale. While it was a populist initiative, the move acted as a great ‘social equaliser’ that had deep connections with Periyar’s self-respect movement. The poor no more had to trade their dignity by depending on ‘upper caste’ households for their entertainment needs and fascination with new technology.

“When ‘Kalaignar TV’ came to my house, I was in Class 10. It took like a week’s time to get the cable connection. You wouldn’t believe, every morning, before going to school, I would switch on the TV, watch the grains on the screen for some time and leave. After me, my brother would turn it on, watch the grains and leave for his work. Then, my mother. This was the level of impact (of the TV),” revealed director Mari Selvaraj, who is known for his hard-hitting films Karnan and Pariyerum Perumal.

This excitement that Mari Selvaraj talks about was beautifully captured by director Manikandan in his national award-winning film Kaaka Muttai (2015). Aishwarya Rajesh—a single mother in the film—gets the ‘Kalaignar TV’ from a ration shop under the Public Distribution System (PDS) and carries it back home on her head. Seeing her with the TV, her two young sons jump up and down with joy and climb atop their house in a local slum to take a connection from the cable line. This scene is an unexaggerated and honest depiction of how the TV became an integral member of many such Tamil families.

Also read: Rocketry to Rocket Boys — India has finally entered era of science films and series

When ‘Oru viral puratchi’ backfired

Actor Vijay’s film Sarkar, directed by A.R. Murugadoss,released in 2018. In the film, Vijay is a corporate company’s CEO who asks his folks to reject ‘freebies’ given by the government. In the song Oru Viral Puratchi, Vijay and other characters throw household appliances like mixie and grinder (given by former chief minister J Jayalalithaa) into the fire.

After watching the film, many Vijay fans from across the state made TikTok videos where they threw such electrical appliances into the fire. Irked by the scene, the All-India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam(AIADMK) party cadre led violent protests at the theatres. To put an end to this, Sun Pictures, the producer of Sarkar, snipped the controversial scene. The production house is owned by Kalanithi Maran, a family member of current DMK supremo and Tamil Nadu CM M.K. Stalin. But it wasn’t just a political tussle that came in its wake—writers, activists, intellectuals and common people were also vocal in their disapproval. They argued that these household appliances greatly reduced the kitchen time of women and relieved them from a lot of manual labour.

Also read:

Good intention, bad portrayal

The critically-acclaimed political satire Mandela (2021) had Yogi Babu playing the character of Mandela, a Dalit barber who is ostracised and placed at the margins of two adjacent villages representing dominant and conflicting castes. The two villages—’Vadakkoor’ (village in the north) and ‘Thekkoor'(village in the south)—are going to elect a new panchayat leader. And needless to say, casteist leaders from both sides want a person of their ‘clan’ to win the coveted position.

As the pre-poll projection shocks them with a tie, the fate of who gets to become the next president now depends on who Mandela votes for. Caste leaders from the two villages try to ‘buy’ Mandela’s vote by showering him with expensive gifts. This was an overt reference to the ‘freebie’ culture in Tamil Nadu. As Mandela begins revelling in his new-found life filled with public attention and material possessions, people around him see a different, side of him come out. That of a ‘greedy’ Mandela.

What the film aimed to say was that lower-caste, Dalit votes are bought using ‘freebies’ and when people accept it, they are shown to be some insatiable opportunists. The political commentary is that people who receive free goods are spoiling the sanctity of democracy. This attempt is quite similar to Bong Joon-ho’s Oscar-winning film Parasite, but both movies end up shaming and demonising marginalised people.

Until 2017, the year when the Goods and Service Tax (GST) was first implemented, Tamil films with Tamil titles were not required to pay entertainment tax thanks to an order passed by Karunanidhi in 2006. Later, under Jayalalithaa’s government, the condition was changed to films having Tamil titles and a ‘Universal’ or ‘U’ certificate from the censor board. This begs the question—to those who campaign against ‘freebies’ in cinema, the tax benefit that the state government gave to the film industry was also, in a way, a ‘freebie’, right?

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)