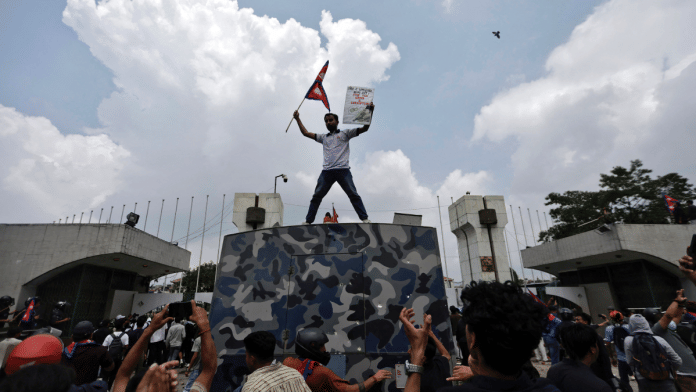

Other than the startling visuals—billows of smoke emerging from parliament, buildings charred beyond recognition, and a city that has traded in a government for its people—the Nepal protests have been characterised by a single, panoptic element. It belongs to Gen Z.

This is a generation that has been made mincemeat. They’re engaged in a perpetual brawl, and they’re always on the losing side. Whether it’s Nepal, Sri Lanka, or Bangladesh, each country’s youth has been slapped with crisis after crisis, one more insurmountable than the next. Flailing economies and an all-encompassing awareness that the rot has settled into the very core of the country have created a generation devoid of hope. The gulf must be filled, and it’s done by way of spectacle. What stands out is the audaciousness of it all—the lackadaisical irreverence that easily slips into violence—and the strange mix of apathy and endurance.

The images will be branded into Nepal’s public memory. A finance minister being dragged on the street, clad only in his underwear. A parliament engulfed in flames. A mob drinking alcohol at a 5-star hotel, only to set it on fire minutes later. What binds these images is the fact that each represents a shade of power. Social media is filled with videos of Nepal’s nepotists boarding private jets, smiling serenely in head-to-toe designer outfits. Many of these accounts have now been deactivated. They’re breaching the untouchable. This protest is about a forceful exchange of power: it’s been wrested from the government by young people.

Discontent is on display daily. A stark refusal to accept power, but a reluctant acceptance of the fact that there is no option but to engage with the powers that be—and that there is no solution to the structures that ultimately seep into every aspect of life. These protests, while triggered by a social media ban, are emblematic of a crisis common to Gen Z across the globe. While there are overarching differentiators and varying degrees—particularly in countries from the subcontinent—the themes are similar. They’re facing stagnation, forced to contend with the knowledge that if something doesn’t drastically change, dramatic as it sounds, they’re not going to be able to live.

This global solidarity has been formed, of course, due to the ubiquity of social media. Entire lives are lived online. The online universe, as has been said time and again, feels as tangible as anything offline.

Digital activism is critical to the rise of any political movement today. And when heralded by young people, it takes on an entirely new vocabulary. The messaging is absurd; typified by memes, it exists in a self-contained universe. Until it doesn’t.

Also read: Why India works. And why Nepal, Bangladesh, Pakistan keep breaking down

Need for spectacle

In an essay titled Theatre of Shame, Charlie Tyson talks about the latticework of internet protests and the buzzwords that accompany them. As of 2022, public shaming was “in vogue”. The generation commanding the internet believes in comeuppance—not in due process. It also begets the question of what the ultimate aim is.

“The dramas we stage on social media, frivolous though they may be, herald a shift in our political culture. More and more of us, now, are always onstage,” Tyson wrote. “These developments have rekindled old worries about the role of theatricality in a democracy—expressed for instance by Plato in the Laws, in which an unnamed citizen frets that Athens is becoming a ‘theatrocracy,’ a state ruled by audience applause and catcalls rather than by law.”

There is a video of a protester dancing, doing a reasonably choreographed jig as the parliament and the Prime Minister’s residence go up in flames behind him. The need, or the want to film a TikTok trending dance reel, is a new-age protest adage. The world is perennially watching you, and the need to perform is woven into the need to protest.

There are many tags attached to Gen Z. They are called the anxious generation, they’re said to have been consumed by the gig economy, and their overuse of the internet is what has fostered this deep-seated alienation. But what also defines them is the refusal to take anything seriously.

This is not to take away from the violence in Nepal, but it’s a testament to how today’s young people interpret global politics. They make it silly, which many people mischaracterise as disengagement.

Social media has mastered the art of invisibilising people while making them feel very seen. It’s almost as if the youth of Nepal knew this. They could protest all they liked on digital spaces, but ultimately, it was all futile. Real–world spectacle is what has served them.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)