Against the bustle of the India Art Fair at Delhi’s NSIC Grounds in Okhla on a manic Friday afternoon, the stacked charpai installation under the blazing sun offered a disarming pause. While voices ricocheted between booths, collectors leaned into negotiations, and curators shepherded groups through the aisles amid the soft clinking of wine glasses, a scaffold of woven beds outside provided a break.

People climbed up, sat cross-legged, lay back, talked, and watched strangers drift below. In a place built on looking, the pressure is always to keep moving—to scan, register, and move on. The charpais, curated by Ayush Kasliwal for Serendipity Arts Foundation, made them stay a little longer.

This need to pause—to sit still in a fast, hyper-curated world—surfaced clearly in a cluster of works that, unintentionally perhaps, were offering comfort without pretending that comfort comes easily anymore.

Amid immaculate booths, a persistent idea threaded itself through the installations this year: Ecology is no longer an abstract anxiety in Indian contemporary art. It has become material, spatial and political.

In Echoes of Earth, curated by Shalini Passi in collaboration with Tara Art, ecology is presented as an unstable system shaped by labour, technology, extraction and survival. The curatorial arc that moves from analogue processes to digital ecosystems, reads less like a showcase and more like a restrained warning. The exhibit insisted that matter itself was made to speak.

Among the five artists in this exhibit, Ann Carrington’s exuberant botanical sculptures, assembled from recycled steel cutlery, were most immediately seductive. But even here, most visitors lingered for only a minute or two. There was simply too much to see.

A space to breathe

Raki Nikahetiya’s FOREST II provided a genuine moment of calm.

Built as a Miyawaki-inspired pocket forest, the installation gathers over 200 indigenous plants and trees inside a structure made from nearly ten tonnes of reclaimed construction material. The idea of “home” is reimagined as a living, multi-species ecosystem. Inside the foliage, were headphones offering nature’s sounds. It was tucked away in the farthest corner of the grounds. Inside the pocket, the noise of the fair softened momentarily.

But soon enough, the rhythm of the fair came back to intrude. People entered, looked around, read a pamphlet, and moved on. A minute, maybe two. The forest asked for more time than the fair could afford.

That tension between what an artpiece asks for and what our pace allows became even more visible at Breathe by Teja Gavankar.

A thatched structure shelters a single rocking bench. As one person sits, their weight causes the entire form to expand and contract. From outside, others witness the slow rise and fall of the structure, a visible breathing pattern produced by a human being inside.

The work is described as a collective lung, a chain of care passed from one person to another. But what stood out the most was how exposed the act of resting becomes. Someone rocks gently as others wait. People gather around and watch a stranger breathe.

But even something as slow as breathing had to compete with a clock that was running out. Visitors waited for their turn, did the act and moved on. The work insists on a slow pace but the fair does not.

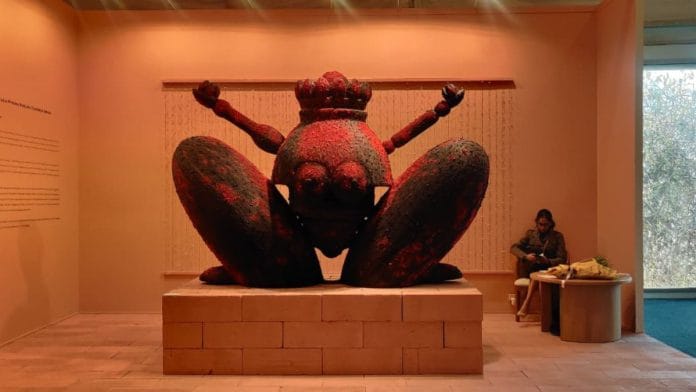

Another piece by Natasha Preenja—a monumental crouching figure of Lajja Gauri, the ancient goddess of fertility whose squatting posture is tied to birth and domestic rituals was beautifully unsettling, in a different way. The thick, scarred surface and compressed posture suggested endurance as much as entrapment. The inscription spoke of practice, bodily memory and lived struggle. It resisted quick reading. I stayed longer than I intended to.

The main takeaway from this year’s art fair was the fragile possibility of stopping, waiting and breathing in forests built from reclaimed metal even as the world of art—and the world outside it—continues to accelerate.

I left grateful for the works that resisted speed and aware of the irony that, in a fair bursting with care, ecology and slow pace, most of us could still spare only a minute or two to stop.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)