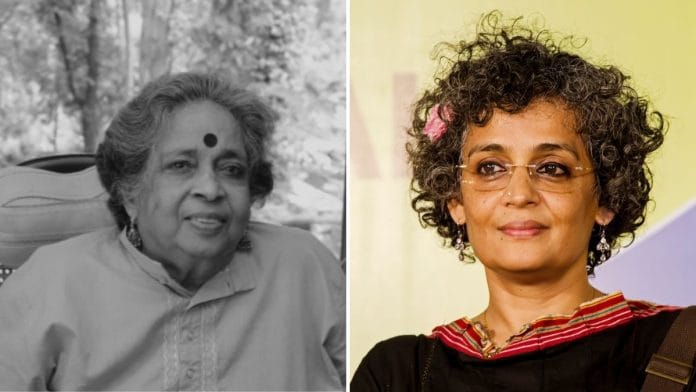

The distance between Arundhati Roy’s first book and the latest is a daughter’s six-decade journey to reach her mother.

In The God of Small Things, Arundhati begins with a declaration that her mother loved her enough to let her go. In Mother Mary Comes to Me, she writes that her brother calls it the only piece of fiction in the book.

She ran away, unable to suffer more humiliation under her mother’s controlling watch.

What is it about feminist mothers and daughters that complicates things? Is the relationship doomed to be fraught?

The memoir attempts to unravel these ties. Arundhati was able to understand her mother as an individual only after “un-daughtering” herself.

This distance, she said at the Kochi launch, “comes from growing up, becoming an adult. It comes from escaping. Once I left, once I saw the world, how much people suffer. I didn’t become the centre of my own narrative.”

Feminists around the world like to talk about how they carry their ‘mother’s wound’. It’s a thing. In Arundhati Roy’s case, it is a bit different. She didn’t see her mother as wounded, but as an inflicter of wounds. When reading the book, one can see her mother as a ‘fascist government’ unto herself.

And Arundhati is an expert in writing about and to fascist governments. Mother Mary Comes to Me is a response to her mother, the centre of her own cult. In Arundhati’s words, she was ‘mother guru’.

Mary Roy was unashamed to fight for her rights. In the town of Aymenem in Kottayam, where she was already ostracised for being a divorcee with two young kids, she fought her brother for equal rights in her father’s inheritance. She won, for herself and for the Syrian Christian women of Kerala.

But no matter what way one spins it, Mary Roy was abusive to her daughter; she humiliated her in public and controlled her with the threat of imminent death, the book says.

“Unquestioning obedience and frequently demonstrated adoration of her were the basic requirements of membership,” Arundhati writes, calling herself and her brother involuntary members.

She’s careful not to rationalise it in the book. There are oodles of respect and sprinkles of love. It’s almost as if Arundhati is the mother, looking back at the antics of an unruly child. But is it possible to re-remember your childhood and overwrite your first, formative memories? And is it even an honest act? That is the quest Arundhati sets out on in her new book.

“Perhaps what I am about to write is a betrayal of my younger self by the person I have become. If so, it’s no small sin,” she writes in the first chapter of her book.

Also read: Arundhati Roy at Kochi book launch: ‘Everyone I love is here. Dangerous, given our govt’

Feminist woman/selfish mother

Arundhati Roy grew up a rebel. Today, as an adult, she is trying to humanise her tormentor. No wonder she describes her mother as both her shelter and storm.

“Throughout my childhood, one half of me was taking hits, the other half was taking notes,” she said in Kochi.

The hits were brutal—something no child should endure or try to understand.

“You couldn’t think of a single intelligent thing to say?” asked Mary Roy to a nearly 15-year-old Arundhati. “Do you think it’s nice for me to have people thinking my daughter is a complete fool?” she thundered.

It’s sentences like this that blur the line between feminist woman and selfish mother. It’s in this blur that daughters like Arundhati Roy anchor themselves. Fitting into the contours that their mothers forgot about. Learning to stand tall in the shadows, plotting an escape.

But even the desire to run away from the selfish mother and not look back, live in your own in an unfamiliar land, constitutes the feminist woman’s blueprint.

Mary Roy’s grave in her beloved school, Pallikoodam, reads: “Dreamer Warrior Teacher”. No mother; she wouldn’t have liked that, writes Arundhati. “Those were not the stripes she strived to earn.”

Maybe Mary Roy loved her daughter, but maybe Mary Roy loved herself more. And that is no sin, just a fact. The burden of the ‘good mother’ tag in Indian culture often involves self-effacing sacrifice. It’s a story of unrealised potential of scores of women.

Mary Roy may not have been the ‘good mother’ that Arundhati wanted as a child, but she fulfilled her own dreams as an individual, as a feminist. And Arundhati Roy, the adult, has recognised it.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)