At the Divya Gita Prerna Utsav in Lucknow on Sunday, 23 November, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath shared what ambassadors and high commissioners ask him when they visit him. “Are you associated with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)?”

“Humlog kahte hain, haan, humlogon ne Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh mein ek swayamsevak ke roop mein kaam kiya hai (we say, yes, we have worked as a volunteer in the RSS),” Yogi said as he went on with his long eulogy of the Sangh. In the audience was RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat, whom Yogi described as a “karma yogi”. Yogi isn’t known to attend any RSS shakha. He was associated with the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), the Sangh’s student wing, during his college days. Bhagwat couldn’t have missed Yogi’s assertion about being an RSS swayamsevak.

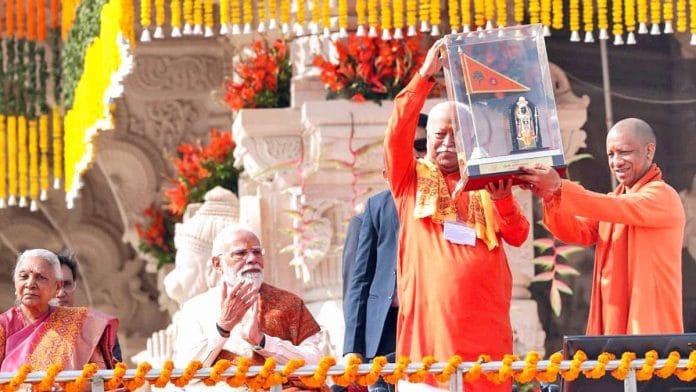

The next day, on Monday, the RSS chief had a 90-minute one-on-one meeting with the CM in Ayodhya. This came a year after their two-hour-long meeting in Mathura. And, on Tuesday, they joined Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the flag-hoisting ceremony at the Ram temple. My colleague in Lucknow, Prashant Srivastava, reports that Sangh functionaries have been holding meetings with Yogi’s ministers and officials to understand the government’s initiatives and priorities and also to ensure better coordination.

An outsider CM

The growing warmth between Yogi and Bhagwat (read the RSS) is unmistakable. The old wariness in the Sangh about an ‘outsider’—someone who can’t be controlled—seems to be melting. There were reasons for this wariness. For instance, Yogi was in the ABVP and yet never an insider. He was in the Bharatiya Janata Party and yet never an insider. Two instances from the past, as cited by Sharat Pradhan and Atul Chandra in their book, Yogi Adityanath: Religion, Politics and Power, illustrate it.

When Yogi was studying at Uttarakhand’s Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna Garhwal University in 1991, he contested the students’ union election as an independent candidate after the ABVP refused to field him. He finished as runner-up while the official ABVP candidate came third. In 2002, he revolted against the BJP and fielded Dr. Radha Mohan Agrawal on a Hindu Mahasabha ticket. Agrawal defeated the BJP candidate. Basically, Yogi can’t be ‘controlled’. He is not an organisation man. According to Pradhan and Chandra’s book, Yogi’s college friends claim that from the very beginning, “RSS and religious and social issues engaged his mind”. For instance, in 1989-1990, he took part in the anti-reservation agitation and burnt VP Singh’s effigy.

RSS insiders explain that Yogi being an outsider is no big deal, as he has always been an ideological fellow traveler. As for the ‘control’ part, even PM Modi had defied his party bosses in the past. In the 2012 Uttar Pradesh assembly election, he refused to campaign for the party because Sanjay Joshi— an ex-RSS pracharak who succeeded Modi as the BJP’s national general secretary (organisation) in 2001 and who later fell out with the then Gujarat CM—was the election in-charge. The BJP president at the time, Nitin Gadkari, had brought Joshi back into the organisation despite Modi’s objections.

Boycotting the UP election in which the BJP fared badly wasn’t enough. A couple of months later, the then Gujarat CM threatened to boycott the BJP’s national executive meeting in Mumbai until Joshi was removed. The party had to give in. Joshi resigned from the body before Modi agreed to attend the conclave.

These instances aside, there is no parallel between Yogi and Modi when it comes to being an RSS or BJP insider. Modi was a full-term RSS pracharak while Yogi never even went to a shakha. Sent to the BJP, Modi worked for years in Gujarat—and then as in-charge of different states and national general secretary (organisation)– before becoming the CM. Yogi was barely ever involved in the BJP’s organisational work, except as an MP.

It is this backdrop that makes growing warmth between Yogi and the RSS so significant. The optics of Bhagwat having frequent closed-door meetings with Yogi, attending functions together, and walking in step with each other in Ayodhya are enough to make all scepticism about the UP CM go away. Few doubt the fact that Yogi Adityanath is the second most popular leader in the BJP. His focus on development—for instance, groundbreaking ceremonies for investments worth Rs 12 lakh crore since 2018—has only amplified his image. That he is honest and has forsaken his family for a larger cause is another amplifier.

Also read: Is Prashant Kishor the Kejriwal of Bihar? Yes, but not really

Yogi’s challenge

If the RSS is seen as virtually blessing Yogi publicly now, it doesn’t really matter whether he is or isn’t an organisation man. Don’t jump to any conclusions, though. It doesn’t make him PM Modi’s successor yet. Yogi has to tick many other boxes before he can think of being considered another Modi at some point in the future.

First, not being an organisation man has the disadvantage of not having his people in the organisation—that is, people who would lobby and fight for his cause. Modi had worked so long for the party in different capacities that he had his loyalists and benefactors not just in Delhi but across the country. Having a party stalwart such as LK Advani as patron steered him through many crises, especially during his chief ministerial days. By the time Advani got wind of his protégé’s real ambitions, the latter had gathered a big band of followers and didn’t need any patron.

Yogi doesn’t have any benefactors or loyalists in Delhi; there aren’t many in Lucknow either. Being his own brand ambassador isn’t an ideal situation for an ambitious leader.

Second, Modi has Amit Shah, someone who has devoted his entire life to his boss’ cause. As I elaborated in my earlier column in September 2022, most of what makes Shah a formidable politician and poll strategist today came from Modi’s playbook. Having a staunch loyalist who drinks, eats, and sleeps politics 24×7 has been a big asset for Modi. Yogi doesn’t have anyone who can be compared to Shah even remotely. The UP CM has a bunch of bureaucrats and non-political associates to fall back on. They can’t take him any farther than the Noida-Delhi border. He needs friends in BJP; there aren’t many today. And there won’t be many if the RSS doesn’t get a say in the choice of the next BJP national president.

Third, Modi has the politically correct caste credentials. Being a Thakur doesn’t help Yogi’s cause. This is one box he can’t tick, even if he wants to. To make it worse, his own party colleagues and allies are already questioning his government’s commitment to the welfare of the backward classes. In 2027, when the caste census data is out, and there is likely clamour for more by the OBCs, think of the predicament and prospects of a Thakur leader.

Yogi Adityanath’s immediate challenge is the next UP Assembly election that’s barely 15 months away. It’s not just the Opposition parties he has to contend with. His detractors within the BJP are no less formidable. If he loses the 2027 battle, there will be no boxes to tick in the foreseeable future. The optics of RSS’ blessings couldn’t have come at a better time.

DK Singh is Political Editor at ThePrint. He tweets @dksingh73. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)