Operation Sindoor has drawn strong criticism from feminists and gender analysts from the subcontinent for its deeply gendered symbolism—reinforcing, as many of them have put it, traditional patriarchal norms, state militarism, and expectations about the ‘protector’ and ‘protected’ roles assigned to men and women in society.

Emerging analyses claim that the operation to dismantle terror infrastructure in Pakistan was an overtly militaristic campaign that not only heightened tensions between the two nuclear-armed neighbours, but also symbolically weaponised sindoor — the red vermilion powder traditionally worn by married Hindu women. It also marked the ‘performative’ presence of women in the Indian Armed Forces, who were positioned as the public face of the operation.

Feminist censure has been intense on social media, stifling an alternative reading of this military campaign. It overshadows and erases the voices of women who lost husbands and other male family members in the brutal terrorist attack in Pahalgam. These feminist grand standings have overlooked the nation’s collective trauma – a body politic scarred by decades of relentless terrorist violence as part of the strategy of ‘bleeding India with a thousand cuts’.

Also read:

Sindoor as a signifier

The name of the Operation is being called exclusionary, gendered, and religious. Some publications suggest that sindoor is an upper caste, North Indian cultural practice based on “patriarchal Hindu ideas”.

This reflects a clear lack of understanding of the cultural, spiritual and political symbolism associated with sindoor. For millions of women across India, and Hindus and Indian diasporic communities across the world, wearing sindoor is often a matter of personal choice, cultural habit, or social tradition. Some women wear it daily due to familial or cultural conditioning, while others may choose to wear it only on special occasions or not at all. Sindoor is worn by Hindu women of all communities – including Dalits, Other Backward Classes, and upper castes – and even by some Christian, Adivasi, and Sikh women.

There is a rich tapestry of sacred and spiritual symbolism around it, where it is offered to gods and goddesses as a symbol of love and devotion. Hindu goddess Durga wears it, not just as an emblem of her marital status, but also as a symbol of her unbridled divine feminine energy and strength. According to the Hindu epic Ramayana, Hanuman, the devoted servant of Ram, once observed Sita applying sindoor to the parting of her hair. When Sita explained to him that the sindoor was a sign of her deep love and eternal devotion to Ram, the clever Hanuman smeared sindoor all over his entire body as a profound gesture of his own unwavering devotion to Ram and Sita. Thus, sindoor transcends its social and cultural connotations and symbolises divine love, loyalty, and sacred commitment.

The depiction of sindoor in a widely circulated cartoon on Pakistani and Bangladeshi social media platforms is a stark example of how cultural symbols can be weaponised for political propaganda. In the image, a Pakistani soldier—representing the state and military establishment—applies sindoor to a feminised representation of India. This act, laden with symbolism, is not simply provocative; it conveys a disturbing message of conquest, ownership, and forced union. By using a deeply intimate and culturally significant symbol such as sindoor, the image frames military dominance as a form of sexual subjugation. This visual narrative draws heavily on colonial metaphors, where nations are gendered—India (or Hindu men) feminised, and Pakistan (or Muslim men) masculinised—and war is cast as an act of domination rooted in militarised masculinity.

As feminists, it is imperative that we resist the urge to strip the sindoor of its sacred meanings and reframe it solely as a symbol of patriarchal oppression, humiliation, and exclusion. While it is essential to critique the ways in which such symbols can be co-opted for coercive and exclusionary purposes, we must also remain critically alert to their layered historical and political meanings. The colonial defilement of the Indian cultural representation of Bharat Mata (adorned with sindoor) was precisely because it carried immense symbolic strength—strength that colonial powers could neither fully comprehend nor control. To dismiss the powerful and culturally relevant symbolism of sindoor outright is to risk echoing those same colonial erasures.

Also read:

Militarism & the woman question

The militarism underpinning Operation Sindoor has also been questioned in some feminist write-ups, arguing that state-led military interventions such as these weaponise feminism to further patriarchal causes. It has been suggested that women also need to wage wars, but only over issues such as “sexual violence, gender-based violence, underemployment, unpaid and underpaid work, and limited reproductive rights”. What often gets overlooked in these assertions is that women have historically performed gendered-war labour across several militaristic contexts, with full fervour and patriotism. Men’s wars have also been women’s wars, and feminist scholarship has long worked to reclaim and reframe women’s roles within war narratives.

Understanding Operation Sindoor as part of the muscle flexing and militarism of two nuclear states alone, and seeing it as a stage for gendered performances, tends to draw attention away from the highly militarised, racialised, and gendered act of terrorism that prompted it. These critiques often fail to account for the violence perpetrated by terrorist groups and individuals, whose actions have inflicted enduring trauma and grief on families and communities.

In Pahalgam, the chosen men were mostly Hindus – marked, othered, and distinguished from the local Muslim population. They were stripped, humiliated, made to recite the kalma (Islamic prayer), and shot point-blank in front of their family. A scenic tourist location in Kashmir, where ordinary couples were enjoying their time away together, was turned into a graveyard. Grieving and traumatised women were asked to inform their government and Prime Minister Narendra Modi, that terrorists had yet again come from across the border to emasculate a nation, a culture, and a religious community with their violence.

The message was clear – India and its (Hindu) men had not been able to ‘protect’ women and their sindoor.

Operation Sindoor was not just an act of patriarchal vengeance but a calibrated and controlled military strategy to neutralise terrorist safe havens in Pakistan. The blanket criticism of militarism as merely a patriarchal tool strips it of its context, the histories that have enabled different forms of meaning-making, and the closures and cathartic outcomes it has for individuals and communities.

The operation carried a deeper meaning, with many seeing it as a punitive yet a symbolic step toward accountability. As one of the survivors, Himanshi Narwal said, “my husband’s soul will rest in peace.” Sangita Ganbote, who also lost her husband in Pahalgam, said: “The action taken by the military is good, and by naming it Operation Sindoor, they have respected the women.” Asavari Jagdale, who lost her father, said that the airstrikes were a real tribute to all those slain in the terrorist attacks.

Also read:

Military women, tokenism

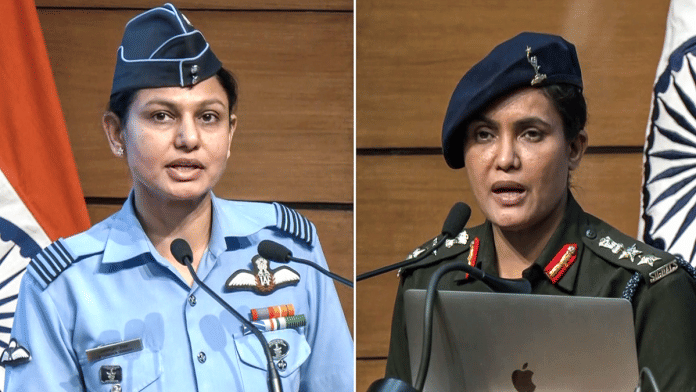

The other issue that seems to have niggled some feminists is the perceived tokenism in the ‘spectacle’ of two Indian women (a Hindu and a Muslim) in the Indian Armed Forces becoming the face of Operation Sindoor. Colonel Sofiya Qureshi and Wing Commander Vyomika Singh appeared alongside Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri to lead the Operation Sindoor media briefings. This may have been a strategic choice, but could there have been a better time for the Armed Forces to showcase their commitment to gender equality? Militaries are patriarchal and male dominated institutions, but women have worked very hard to break the glass ceiling. Is it really feminist to deny these women their agency – officers who have risen through the ranks on the strength of their competence – by reducing their presence to a mere gendered performance of the state, a spectacle, or some form of tokenism? Should one flatten their identities instead of recognising them as autonomous individuals operating within complex institutional structures?

Militaries are not upholders of gender equality, but surely one can appreciate the visibility of women officers contributing in a male bastion. Feminists globally have long advocated for more women in militaries, not always arguing that it leads to a gender equal institution, but that it opens up spaces and opportunities for women.

Paradoxically, had the two women officers been men, the feminist critique would likely have condemned the absence of women in a military operation named “sindoor”, calling out their erasure from a narrative supposedly centred on them.

Also read:

Reclaiming feminism

Operation Sindoor has been denied its “feminist” overtures – on the grounds that its use of the word sindoor reinforces a cultural problematique, and that any “war is inherently patriarchal.” However, history is replete with female warriors and gender struggles where violence sometimes becomes essential to protect cultures, language, territorial integrity, sovereignty, and national values from coloniality and aggression. For many women, the ‘natural instinct’ to care is not in opposition to arming themselves—it is precisely an extension of that ethic of care.

Women are not solely defined by their gender – they also possess a sense of belonging rooted in their communities, cultures, religions, and nations. These intersecting identities shape both their individual and collective experiences of power, trauma, and representation.

Through this article, we would like to restore feminist agency and visibility to the Indian women whose husbands and other male family members were shot in front of them in Pahalgam, and the thousands of other women who have died or lost family members in the scourge of terrorism perpetrated by Pakistan-based groups. Operation Sindoor, showcasing India’s zero-tolerance for terrorism and signifying a ‘new normal’, is an opportunity for feminists to recognise that sometimes the military labour of the state also restores dignity to its citizens. And it strongly challenges a specific form of unaccountable, cowardly, highly-gendered, racialised, and patriarchal armed violence.

Suruchi Thapar-Björkert is Professor in Political Science at the Department of Government, Uppsala University, Sweden. Swati Parashar is Professor in Peace and Development at the School of Global Studies, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

The authors are peddling views which are in line with similar discussions in Pak media. So – I hate when they try to broad brush under ‘the Sub-continent’ garb. If they have any concerns -hope they do understand that this was a political messaging – which is relevant to the society it originates from. Simply writing from a Swedish desk – however polished and agonized – still seems very much irrelevant from Chandni Chowk!!

Here comes the “Concerned Indian”. An Indian (hard to verify, might as well be a Pakistani or a Bangladeshi) whose sole “concern” is about Hindutva dominating over other ideologies. An idiot who thinks that sindoor is “state-sponsored gendered metaphor tied to marital sacrifice, widowhood, and Hindu religiosity, effectively flattening India’s cultural and religious diversity under a saffron-tinted banner.”

Such morons can be found in abundance in the social science and humanities faculties of Western universities. These are the ones who take out pro-Hamas rallies and celebrate the October 7 attacks on Jews.

In India too, enjoying the patronage of the Congress government for the better part of independent India’s history, these lunatics came to occupy senior academic and research positions in almost all central and state universities. Professors like Nivedita Menon and Ira Bhaskar at JNU are exemplary members of this tribe. The hallmark of this tribe is their absolute silence on Islam and it’s depredations on Muslim women and non-Muslim communities. They do not speak a word on the atrocious treatment meted out to Muslim women in Islamic communities. Or the medieval and bestial rules imposed on non-Muslim communities in Islamic nations.

This tribe thrives in the academic ivory towers of liberal-secular democracies and it feeds on it’s own. It feasts and scavenges on it’s very own people – be in India or in Western nations.

It gives Islam and it’s adherents a free pass. These clowns rant and rail against the custom of “purdah” in certain Hindu communities but gleefully defend the burkha as “a matter of individual choice”.

Ms. Shilpi Hazarika has rightly observed that these people are insufferable self-righteous idiots.

Thanks & Regards,

Prof. Amita Giri

ECE, IIT Roorkee

I have had the misfortune of being acquainted with Swedish Intersectional Feminists. They are a bunch of insufferable self-righteous idiots. Their holier-than-thou approach towards every single socio-economic issue and hankering for attention turns off even the most genuine believer of their causes.

If Sweden is suffering nowadays from illegal immigration related crime, drugs and violence, it is due to idiots like these. The beautiful country is just overrun with morons like these.

This article delivers is a troubling synthesis of token feminism, cultural nationalism, and selective postcolonial guilt-washing & an attempt at building Hindutva inflected state action as feminist resistance, and to delegitimize anti-caste socialist and liberal feminist critiques by calling them insufficiently nuanced or overly Western. These are the issues I have with this article:

1. The authors insist that sindoor has “multifaceted significance.” While it may hold personal or regional meaning for some, using it in the naming of a state-led military operation aimed at retribution does not pluralize its symbolism: it codifies it. In this context, sindoor becomes a state-sponsored gendered metaphor tied to marital sacrifice, widowhood, and Hindu religiosity, effectively flattening India’s cultural and religious diversity under a saffron-tinted banner. Feminists have long critiqued such symbols for their role in upholding patriarchal control over women’s bodies and identities. This is not cultural nuance, it’s gendered nationalism in disguise.

2. The article highlights women officers like Wing Commander Vyomika Singh and Colonel Sofiya Qureshi as symbols of gender progress. But showcasing individual women in uniform, without reckoning with the deeply masculinist structure of the military, amounts to tokenism. Real feminist engagement would interrogate the gender hierarchies, exclusions, and abuses that persist within these institutions. Visibility alone is not justice, especially when used to shield the institution from critique.

3.By framing feminist critiques as insensitive to “national trauma,” the article falls into a familiar rhetorical trap: branding dissent as unpatriotic. This strategy is not new, nationalism frequently uses emotional appeals to unity to discredit those who question the state’s gendered violence. Suggesting that feminist analysis must defer to national sentiment, especially after terror attacks, is a form of tone-policing that undermines precisely the kind of critical inquiry feminists bring to militarism and security discourses.

4. The article makes a baffling move by invoking the Ramayan, particularly the version by Tulsidas , a 16th-century Bhakti poet known for reinforcing caste hierarchies and patriarchal norms. This selective invocation of scripture, paired with the use of sindoor (a Hindu, Hindi upper-caste word & symbol), aligns more closely with Hindutva cultural nationalism than with any intersectional feminist tradition. Feminism, especially in the South Asian context, cannot ignore the caste and religious politics embedded in these cultural references. Using these symbols uncritically, and then shielding them with academic posturing, is not just poor scholarship, it’s ideological obfuscation.

5. The authors fall back on a tired postcolonial reflex: blaming colonialism for gendered oppression while ignoring the Brahmanical and patriarchal structures that predate and outlive it. Feminist critiques of nationalism, militarism, and cultural symbolism are not simply colonial leftovers, they are rooted in longstanding radical, Ambedkarite, Marxist, and Dalit feminist traditions. To suggest that such critiques lack “local authenticity” or postcolonial sensitivity is not only dishonest but deeply exclusionary.

6. Perhaps the article’s most significant failure is its refusal to meaningfully address how militarism itself is gendered. Military institutions are built on hierarchies, domination, and violence, values that are fundamentally at odds with feminist visions of justice. Romanticizing a military operation through the lens of widowhood and sacrifice merely reinforces the idea that women’s value lies in their capacity to mourn, wait, or avenge. This isn’t empowerment, it’s aestheticized grief, co-opted for nationalist ends.

This article presents itself as a complex, thoughtful engagement with gender and statecraft, but ultimately it offers cover to a deeply regressive politics. It hijacks the language of feminism and postcolonialism to sanitize Hindutva inflected nationalism, tokenism women’s military participation, and dismisses radical feminist dissent as unsophisticated or Western. This is not intersectional feminism. It is intellectual camouflage for cultural authoritarianism, and it deserves to be called out as such.

Because nothing screams intersectional feminism like repackaging Hindutva nationalism in sindoor, silencing liberal & socialist feminists with ‘postcolonial nuance,’ and calling it ‘diversity of thought’ while marching to the drumbeat of bigotry. Love how this is written by two academics sitting in the West & enjoying the perks of a liberal society that challenged such bigotry & repugnant nationalism, while they help dismantle it in Global South, with the help of racist whites who like nothing more than collecting brown & black friends & have them tell them how evil they are, so they can feel superior about their continued power chokehold over rest of the world.. Lol!

The Print’s stated narrative has been to find holes, and magnifying them, even if such holes are non-existant. It tries to be objective in its reporting, but slyly inserts certain statemenrs or observation or reporting that certainly are biased & unfounded. Remarkably pseudo

These guys don’t get tired of being ridiculed in the comments section. Women are from Venus is an outdated trope, but these woke fundamentalist do behave like they were born and brought up on Another planet, maybe Venus. Being progressive does not mean totally sideline ones cultural roots and slander everything that a culture inherits. It means work diligently to pull traditional cultural aspects towards a modern world whilst maintaining the essence of the thought behind it’s genesis. Woke fundamentalists want to reject everything from the past and build a whole new world with rules which they get to define.

Pseudo-feminists like Ms. Vaishna Roy (Editor, The Hindu) are the problem here.

They do not have the ability or even the honest intent to solve a problem. But they are forever aggrieved about perceived slights and insults. Their understanding of “feminism” is far removed from the genuine struggle for equality and empowerment the word embodies and is deeply perverted. Such perverse conceptualization of a genuine quest coupled with the upper class and upper caste privileges gives birth to a weird philosophy of life. One that can thrive only within the confines of centrally air conditioned homes and offices.

Ms. Vaishna Roy and others like her are the flag bearers of this unique and perverted ideology which masquerades as feminism.