Are we beggars for these politicians to hand out sarees and dhotis? Let us ask for jobs, not sarees,’ says ‘superstar’ Rajinikanth in the 1993 Tamil film Valli, as an article in The Print pointed out. Three decades later, the nation is still debating ‘freebies’ versus ‘welfare’. As always with the ‘superstar’, there are several profound political and policy questions raised by this seemingly innocuous ‘filmi dialogue’.

Are sarees a freebie? Is the government’s role only to provide jobs and not sarees? Are voters vulnerable to such ‘freebie’ promises of political parties during elections? Are providing jobs and sarees mutually exclusive? Should an elected state government decide how to spend the state’s money? The average Tamilian earns Rs 2.25 lakh while the average Bihari earns just one-fifth, Rs 45,000. Does that imply free sarees are a wasteful ‘freebie’ in Tamil Nadu while it may be an essential ‘welfare’ in poorer Bihar? If yes, who decides this, and can there be a rules-based order in determining ‘freebies’? This is a far more complex debate than what Rajinikanth thinks of freebies and welfare.

Economists use terms such as public goods versus private goods and merit goods versus non-merit goods to make a distinction. But even the most ardent ‘limited government’ economists agree that these distinctions are very fungible and are no ‘Lakshman Rekhas’. A laptop may be considered a wasteful freebie but as the pandemic revealed, they were essential public goods for education. So, what may be deemed a ‘freebie’ today may become a required ‘welfare’ tomorrow, for example, free internet. Or good quality sarees that may be deemed as a wasteful expense in a rich state like Tamil Nadu may be a necessity in a poor state like Bihar to protect the right to dignity of poor women. Some argue that it is best for governments to provide cash to people, rather than sarees, medicines or laptops, which will give them the freedom to spend on whatever they need. Ironically, the same economists that lament government ‘freebies’ also argue that providing cash to people will make them lazy and lure them into buying alcohol or other wasteful things, rendering the labourforce unproductive for the economy. They neither trust the government nor the individuals to spend money wisely. Pray, who then?

It is a futile effort to come up with a rules-based order to prescribe a list of freebies and welfare for state governments to spend their money on. What an elected state government should spend its money on is best left to be negotiated between the government and its voters. The act of politics represents that negotiation, where if enough voters feel that the government is wasting their tax resources, the opposition parties will make it a big issue and the voters will eventually express it on the EVM.

Also read: As Congress mulls next president, the flip side of inner party democracy

Beyond freebies versus welfare debate

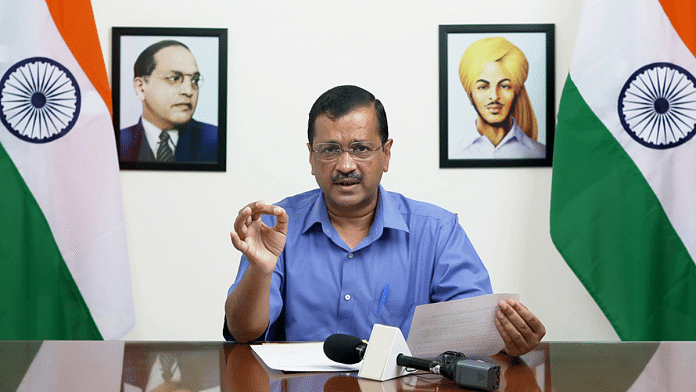

The other important question that Rajinikanth raises, not directly but implicitly, is – do voters get fooled and swayed by symbolic delivery of ‘freebies’ rather than more important needs such as jobs? There is no evidence to show that voters get overly influenced by such promises of ‘freebies’ and vote accordingly. Tamil Nadu, which is often hailed as the epitome of election freebies culture, has voted against the incumbent party in every election from 1991 to 2011 despite such promises. While it is true that a party such as Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) promised free electricity to voters in Punjab, it is wrong to imply that it resulted in their electoral victory. I would wager that, had AAP not promised free electricity or even made more realistic promises of eliminating free power for rich farmers who can afford to pay for it, they would have still won a handsome victory. It is important not to conflate such promises with electoral outcomes.

The current debate has dwindled into a ‘freebies’ versus ‘welfare’ one: who has the right to dictate expenditure or my-freebies-are-better-than-yours. This masks more serious underlying issues. The fountainhead of this debate is a report by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) that claimed state finances are in terrible shape due to fiscal profligacy on ‘freebies’ by governments. Add to this, an earlier 2011 petition in the Supreme Court that challenged the ability of state governments to use taxes collected from a few to pay for ‘freebies’ for all. The RBI report and the Supreme Court petition deserve more serious discussion and analysis than the current ‘freebies’ versus ‘welfare’ fight.

It is true that state government finances are in a perilous state due to excessive debt and run the risk of impacting the sovereign rating of the country. But the RBI’s role is limited to restricting excessive borrowings of states rather than dictating to them on how to spend their money. The RBI can impose harsh conditions and penalties for deeply indebted state governments to borrow further either by denying them credit or raising their borrowing rate steeply. Prescriptive judgements on good versus bad expenditure by an unelected RBI to elected state governments will be countered and opposed vehemently and justifiably so.

Also read: ‘Freebies’ may give temporary respite to masses, but can put a dent in India’s economy

If ‘givers’ decide for the ‘takers’

The argument about using taxes of a few to pay for freebies for all is a slippery one. First, everyone pays taxes in the country, albeit some more than others. Second, redistribution is the very essence of democracy and it is unreasonable for the ‘givers’ to prescribe what should be given to the ‘takers’. If individual ‘givers’ demand to dictate the type of expenditure incurred for the individual ‘takers’, then what is to stop richer states such as Maharashtra and Gujarat from saying that their money should not be used by the Centre to fund programmes such as farm loan waivers and instead only be used for, hospitals, in poorer states of Bihar or Uttar Pradesh? This can shake the foundations of fiscal federalism and the unity of the nation at large. But the ‘givers’ have every right to protest using non-violent methods such as a ‘tax satyagraha’ or ‘tax avoidance’ to air their grievances and demand greater accountability and transparency from their state governments.

In the larger context, this debate is healthy. It has brought many issues to the forefront such as perilous state finances, federalism, populism and election promises. Pressure from the RBI, taxpayers and federalist forces will hopefully establish an equilibrium that balances all stakeholders and results in improvement of state finances and quality of expenditure.

Praveen Chakravarty is a political economist and a senior office bearer of the Congress party. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)