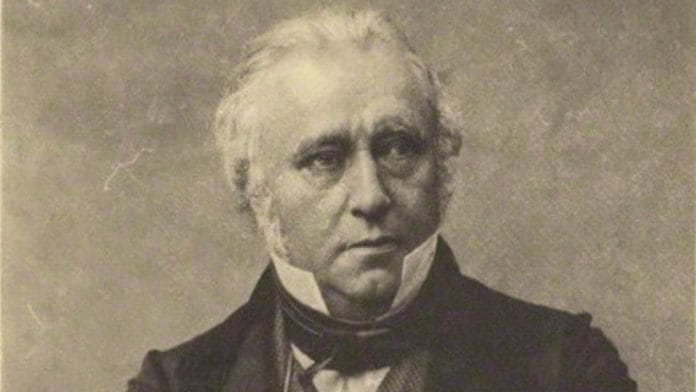

A “Minute” that will live in infamy: 1835, a memorandum published by Thomas Babington Macaulay, declares that “a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia,” and calls for “a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals and in intellect.” About 190 years later, the Prime Minister of the Republic of India, hot off the heels of an election victory, declared the end of Macaulay’s vision, that “we will rebuild pride in our heritage, our languages, and our knowledge systems.”

On this matter PM Modi’s stance is certainly compelling. But the legacy of colonial thought and, to use the Prime Minister’s words, “slavery mentality” will not disappear without deep, provocative introspection at every level of our national imagination. While it is certainly true that Nehruvian liberalism owed much to Western thought, it is also true that Hindutva—positioned as the “decolonising” alternative—still draws upon colonial attitudes toward history, religion, nation, and state.

Macaulay and British attitudes

Macaulay, the British parliamentarian, has long been responsible for the imposition of English on an apparently unwilling populace. He circulated his infamous “Minute” during debates on the East India Company’s patronage of Arabic and Sanskrit education, which had followed—at a smaller scale—the patterns established by the Mughal Empire. However, as historian Suresh Chandra Ghosh writes, private academies for English education had already begun to spring up in Calcutta by the time, and reformers such as Raja Ram Mohan Roy saw the language as a means to challenge obscurantism.

Despite the infamy of Macaulay’s 1835 Minute, specifically his views on Hinduism and Sanskrit, he didn’t have that much influence on the outcome. A single British parliamentarian could not, as the Prime Minister said in his speech, “uproot the Gurukul system”. This was in part because the Gurukul system was never a state-driven mechanism for mass education; even if we were to consider the medieval system of agraharas and mathas “Gurukuls”, all indications are that they were for elite (usually Brahmin) men. Moreover, the Governor-General, Lord Bentinck, had already made moves toward English education as early as 1829. To Bentinck, the target was Persian, the Mughal and Maratha language of administration—rather than Sanskrit, which at the time had lost its political centrality.

With all this said, Macaulay’s vision of a class of “civilised” brown sahibs did essentially come true. By the time of the freedom struggle, a huge swathe of the Indian elite had studied in English (often in England), and colonial modernity had effectively severed their connection to various religious, caste, and ethnic traditions. As historian Thomas Metcalf writes in The New Cambridge History of India: Ideology and Empire, “contemporary European, especially British, culture alone represented civilisation… No other cultures had any intrinsic validity.” The British insisted on seeing India’s complex histories and cultures through “rational” eyes, which is to say, through European ideologies that sought to explain their ascendancy over the world. Europe already had a history of centuries of rivalry with the Muslim “Other”, especially the Ottoman Empire. As such, they simplistically insisted that India was a land of Hindus conquered by Muslims, and they believed that they could define such a thing as a pure Hinduism and pure Islam from a “rational” approach to sacred texts. Any discrepancies between theory and India’s unbelievable diversity of practice were simply evidence of degeneration from an imaginary perfection.

Also read: How did Nepal become a ‘Hindu Rashtra’?

Constructing India’s history

This attitude also fed into British perceptions of India’s history. James Mill, a man who could speak no Indian languages and had never visited India, believed that this made him an especially objective historian. In his History of British India (1817), he made a tripartite division of a stagnant Hindu India, transitioning to a decadent Muslim India, and finally to a progressive British India. However, the perception of this “Hindu India” improved over the decades. The discovery of the Indo-European language family, Metcalf demonstrates, was used by German Romantics to claim that India’s ancient Aryans were linked to the German race. European “rationalists” were fascinated by the enlightened conceptions of Buddhism and the early Vedas, because they saw in them a reflection of “Classical” Greece, the purported ancestor of western civilisation.

An explanation then had to be found for the “decline” of India, to which the British solution was first to blame the tropical weather, which they thought made Hindus “submissive”. More influential were texts like Elliot & Dowson’s History of India as Told by its Own Historians (1867–77), which read medieval Muslim chronicles as evidence of foreign tyranny imposed on Hindu India, further reinforcing the idea of Hindu “submission” while exoticising Muslims as vigorous, alien conquerors who could occasionally be respected. Vincent Arthur Smith’s Early History of India further cemented the idea of a Hindu Golden Age ended by “Muhammadan conquest”. Even so, a sense of Indian inferiority—both Hindu and Muslim—continued to endure. As racial theory took hold in Europe, India’s indigenous “races” were blamed for the decline of “conquerors” such as the Aryans and Mughals. Racial mixing, according to ethnographers like HH Risley, had enervated all of India’s conquerors, hence explaining the “inevitable decay” even of “brilliant” Muslim conquerors. It was from this muddle of racism, Orientalism, and Western liberalism that India’s freedom fighters would formulate their own ideas of history.

It is somewhat ironic that the most influential of these freedom fighters were the very class of “brown sahibs” that Macaulay had once envisioned. English education was an excellent way to enter the ranks of the colonial elite, but for those who grew disillusioned, English also offered a way to absorb, repurpose and broadcast in the global language of power. Historian Partha Chatterjee, in his classic Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World, describes the narratives of the freedom struggle as “derivative discourse”. Jawaharlal Nehru and Mohandas Gandhi absorbed the European rhetoric of progress and liberalism, believing it was the duty of the state to ‘uplift’ its people (which is to say, to impose the Congress’ idea of ‘upliftment’ with absolute moral certainty). VD Savarkar took up European revolutionary thought and racial nationalism, and MS Golwalkar was particularly taken with the developing vocabulary of fascism, with its focus on martial discipline and strongman authority. Savarkar and Golwalkar, in particular, retooled the European idea of fatherlands belonging to singular races.

Also read: Zohran Mamdani’s New York win revives a forgotten history — of Gujarati Muslim cosmopolitanism

What does decolonisation mean?

Superficially, their views of history might seem completely divergent, but all accepted the British conception of Hindu, Muslim and British India. Dalits and Adivasis, all the groups in between and beyond the structures of caste Hindu society, simply had to be absorbed into these grand narratives. All these thinkers shared a romantic notion of a Golden Hindu India, because of their focus on texts generally written by elite men. All insisted that these texts could reveal some essential core of Hindu civilisation: To Gandhi it was the Bhagavad Gita, to Savarkar it was the Vedas, which he saw as a rational set of texts. All agreed that there had been a decline: The main point of divergence was in its cause. Savarkar and Golwalkar held that it was Muslims, as a “foreign race” who had caused “a thousand years of slavery”—ironically, closest to the British view. Nehru, while acknowledging religious violence, held that the “Muslim period” was by and large a period of syncretism, emphasising the absorption of Muslim dynasties into Indian social structures. To Nehru, the British were the cause of all of India’s problems—yet, as Prime Minister of independent India, he expanded the License Raj that characterised colonial rule, with regime-aligned firms like those of the Tatas benefiting in place of British conglomerates.

So what does decolonisation really mean in 2025, and what will it mean in 2035, by which time Prime Minister Modi wants India to shed Macaulay’s legacy? If Nehruvian liberalism must be jettisoned as a product of Macaulay’s brown sahibs, then what makes Hindutva—emerging from the same modernist intellectual environment and social classes—more indigenous? When will we be able to create a sense of the past that doesn’t buy into colonial binaries, which acknowledges that no age, except the present, can be Golden for us all? When will all regional languages and cultures be spoken of with the reverence once reserved for English, and now for Sanskrit? And when will the voices of marginalised peoples, ignored and spoken over century after century, stop being jailed, persecuted, appropriated? Then, and only then, will we no longer be enslaved.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of ‘Lords of Earth and Sea: A History of the Chola Empire’ and the award-winning ‘Lords of the Deccan’. He hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti and is on Instagram @anirbuddha.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)