The resounding electoral success of the Bharatiya Janata Party in 2019, howsoever unexpected, is the result of an ideological shift in Indian politics. The immediate context of the 2019 Lok Sabha election did bear upon the BJP’s victory, but profound structural changes were more consequential. The increasing size of the middle-class and a new form of ethno-political majoritarianism, delinked from a religious Hindu nationalism, helped the BJP shed its tag as an upper-caste party mainly confined to the Hindi heartland.

The BJP’s rhetoric is that opposition parties have indulged in politics of minority (read Muslim) appeasement, whereas the BJP believes in treating everyone equally. The BJP has always stressed that it stood for the development of all, and appeasement of none. This strategy has allowed the BJP to draw support among those Hindus who have come to believe that, before the BJP, India’s democracy favoured minorities. The BJP’s rhetoric, not surprisingly, can be interpreted as full of prejudice, especially towards Christians and Muslims.

Short-term factors in 2019

The short-term factors such as the popularity of Narendra Modi, BJP’s organisational advantages, the issue of national security, and the BJP-led government under Modi being seen as taking care of the poor are linked to our main argument about the longer-term ideological consolidation in favour of the BJP.

Similarly, in the past two decades, the BJP has come to ‘own’ the issue of national security and fits neatly into the party’s ideological repertoire. These factors — along with the use of social media to reach more voters ‘directly’ and its success in portraying welfare benefits as a direct connection between the household and the party — reflect the shifting middle ground of Indian politics.

Also read: Both Hindus and Muslims want development. But that’s where the similarity ends

Longer–term factors in 2014 & 2019

Ideology and electoral success of BJP

First, there has been a perceptible change in the ideological make-up of the median voter. It is hard to know whether the BJP has pushed the political median towards the centre-right or whether the party is merely capitalising on the shifting middle ground.

Transformation of BJP’s social base

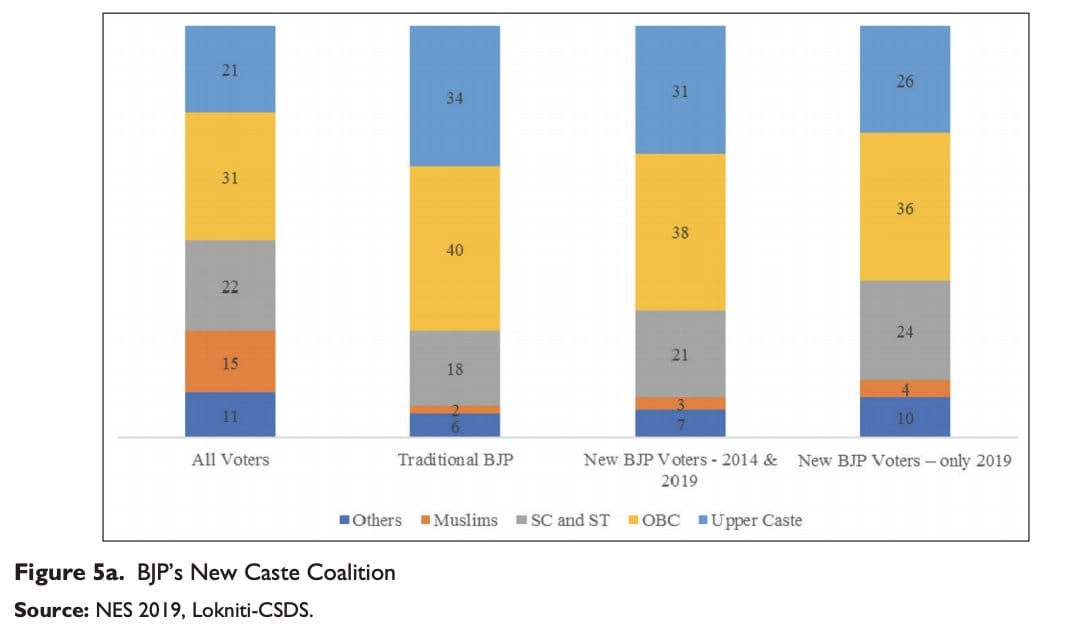

Second, while the BJP leadership has remained upper caste, its social base has slowly become more reflective of a larger swathe of Hindu society.

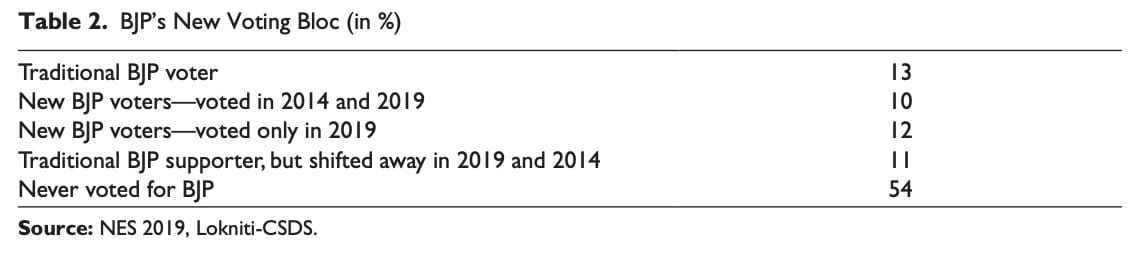

Who are these new BJP voters? To understand the changes within BJP’s social coalition, we used three separate questions from the National Election Studies (NES) 2019. The NES asks whom the respondent voted for in this election, in the previous election (2014), and whether the respondent considers herself a traditional supporter of any party. Approximately 13 per cent of our respondents considered themselves as traditional voters for the BJP; additionally, 22 per cent are post-Modi BJP voters, and 11 per cent are outgoing BJP supporters (Table 2).

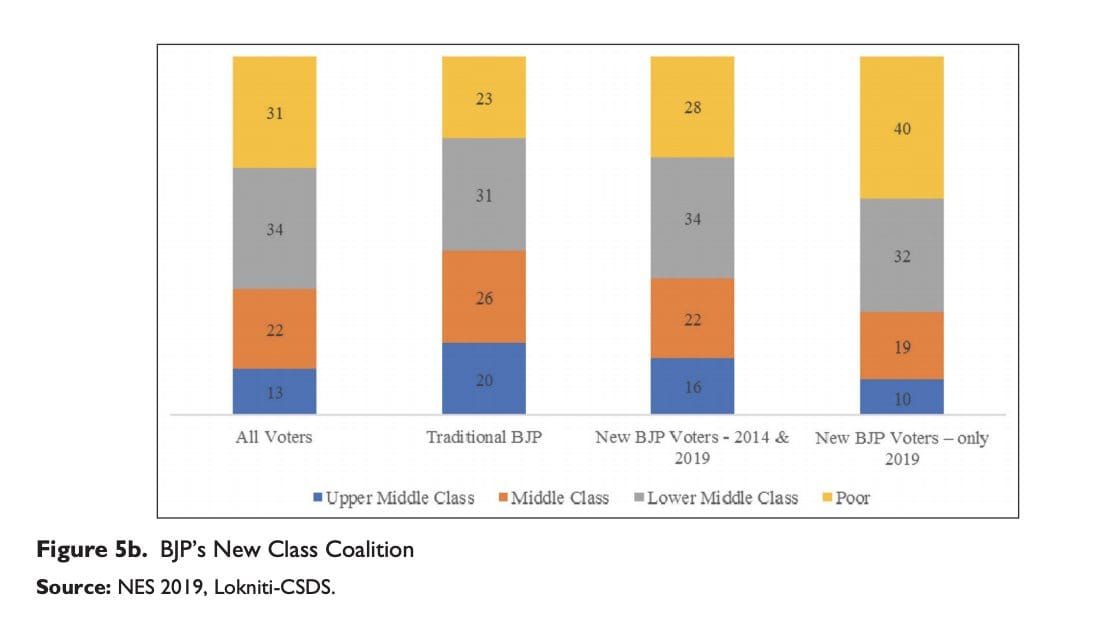

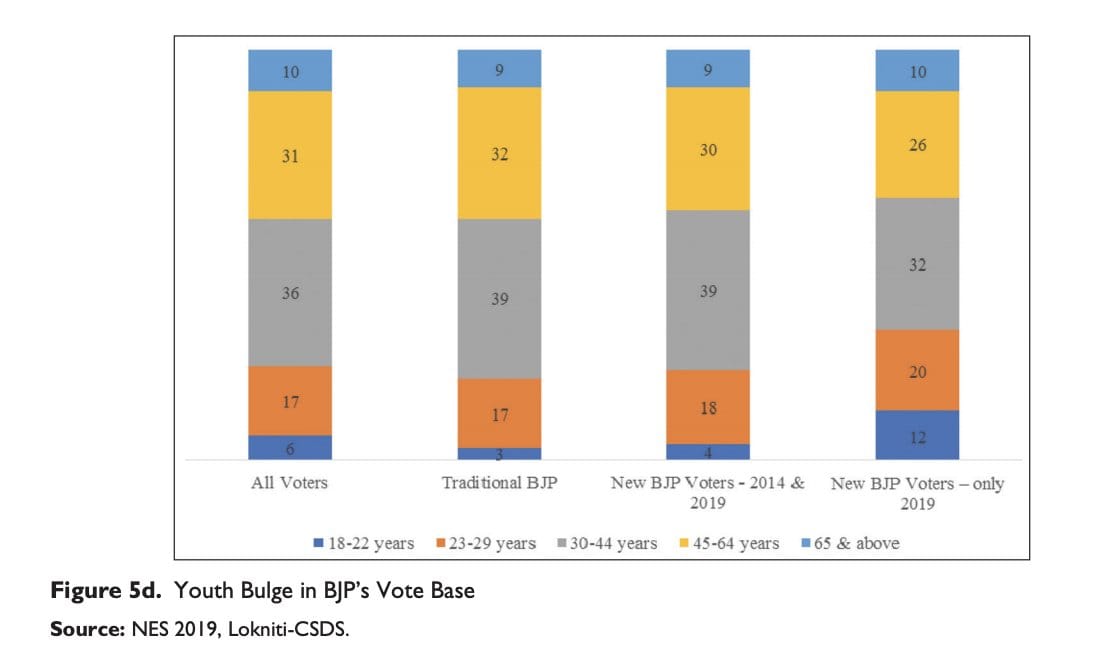

The newer voter for the BJP is more likely to be from the lower castes, is rural, less educated, and younger (Figures 5a–5d). The profile of the first-time BJP voter in 2019 almost mirrors Indian society, with the singular exception of religious minorities. The more dramatic shift is the changing nature of the social classes that supports BJP. Traditionally, the upper and middle classes supported the BJP in large proportions. This changed in 2014 when the BJP won votes from the lower middle classes. The new voter for the BJP in 2019 comes mostly from the poorer segments of society.

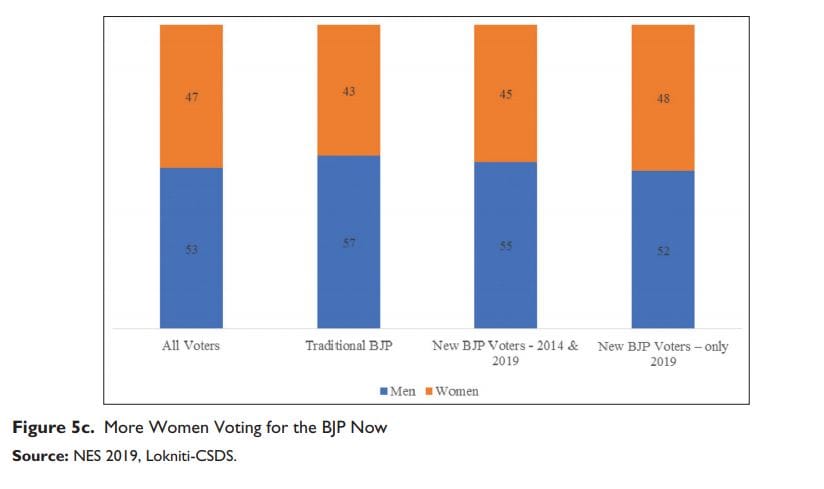

Another interesting feature of the BJP’s new social coalition is that the party managed to close the gender gap among its voting population. Previously, the BJP had a disadvantage among women voters. The BJP’s social base is now also more reflective of India’s age pyramid.

Ideological consolidation and BJP’s new social coalition

Third, India is undergoing a massive demographic transition and the changes in India’s political economy and the information environment are having significant electoral consequences.

The politics of recognition scale is composed of two categories – ethno-political majoritarianism and affirmative action (or reservations).

The index of ethno-political majoritarianism captures the sentiment that will of the majority should prevail, minorities should adopt the custom of the majority, and that the government should treat both groups equally. We use two questions to measure Hindu nationalism — whether India is primarily a land of Hindus and whether a respondent is more likely to consider Hindus as more nationalist than Muslims.

We created a measure of the Modi effect by combining a respondent’s choice for India’s next prime minister and whether Modi leading the BJP’s prime ministerial candidacy made a difference to their voting decision. We also created an index of socioeconomic status among the Hindu voters by combining information on their economic class and caste position.

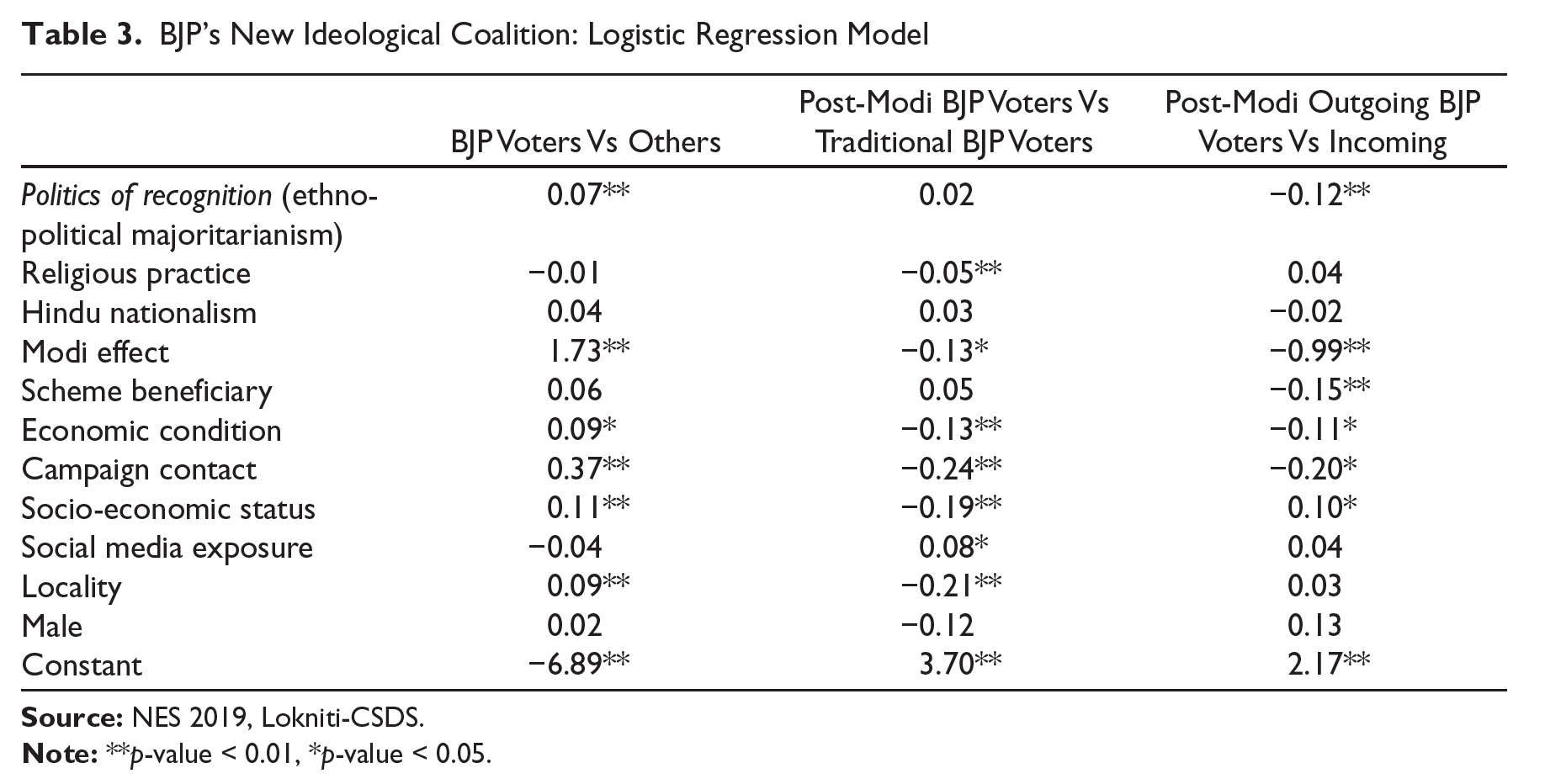

In the first model, we compare BJP voters with those who did not vote for the BJP in 2019. Not unexpectedly, we find that a mix of short- and long-term factors can help distinguish BJP voters from others. BJP voters are more majoritarian but not as religious or in favour of Hindu nationalism as those who did not vote for the BJP. These findings suggest that there may be the emergence of a new kind of majoritarianism (whose self-definition may still be ‘Hindu’), which is independent of religious practice and more conventional views of Hindu nationalism.

There is indeed a Modi effect: respondents who preferred Narendra Modi as the Prime Minister were far more likely to vote for the BJP. Urban residents and respondents of higher socioeconomic status had a greater probability of voting for the BJP. So do those who were contacted by the BJP, and whose economic condition had improved. Contrary to the widespread expectation, receiving government benefits had no particular bearing on BJP’s vote.

There is, however, a significant difference between traditional BJP voters and those who began voting for the BJP in 2014 and 2019. The model in Column 2 of Table 3 distinguishes post-Modi BJP voters from those who identify themselves as traditional BJP voters. The results are striking. For the post-Modi BJP voter, religiosity is less likely to influence the vote for the BJP compared to the traditional BJP voter. Hindu nationalism has the same effect for both new and traditional voters of the BJP. Modi, surprisingly, has less sway over the new BJP voter. The new voter of the BJP is more likely to be less well-off, more likely to be from a rural area, less likely to be male, and more exposed to social media.

An examination of the differences between those who left the BJP after Narendra Modi became the party’s prime ministerial candidate and those who voted for the BJP after 2014 illustrates quite clearly the role of ideology (Table 3, column 3). Those who did not vote for the BJP post-2014 are less likely to favour ethnopolitical majoritarianism and be swayed by Narendra Modi even after controlling for short-term factors such as their economic condition, whether they benefitted from schemes, and contact by the BJP during the campaign.

The BJP’s inroads among the more disadvantaged become much more apparent in this model. The post-Modi outgoing BJP voters tend to be more involved in religious activities compared to the incoming BJP voters post-Modi. Interestingly, in the previous model, we saw that the post-Modi BJP voters are less involved in religious activities compared to the traditional BJP voters. The BJP has a reason to worry: preference for the party among those who practice religion more avidly is getting weaker in comparison to the past.

Also read: Foolish to think Hindus who voted Modi twice will shift due to threat to Muslim citizenship

Ethno-political majoritarianism & BJP’s expanding catchment

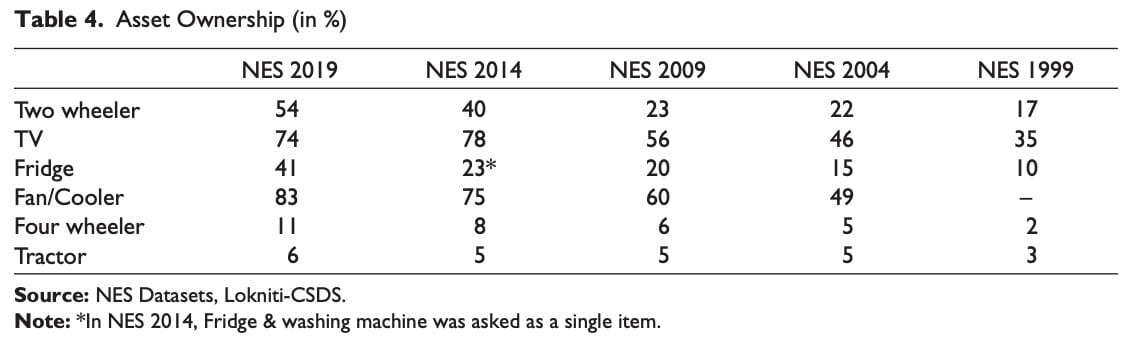

There are many more Indians living in urban areas than ever before. In 1991, the urban population was approximately 25 per cent; that share is likely to increase to more than 40 per cent by 2021. Similarly, the proportion of middle class has increased manifold. Many more respondents report owning assets usually associated with the middle class (Table 4).

The self-identification of Indian citizens as members of the middle class has also increased in the past two decades. In 1996, only 30 per cent of respondents to the Lokniti-CSDS surveys self-identified as middle class, while 62 per cent identified themselves as working class. In 2019, these proportions had flipped: 32 per cent identified themselves as working class and 58 per cent identified as middle class.

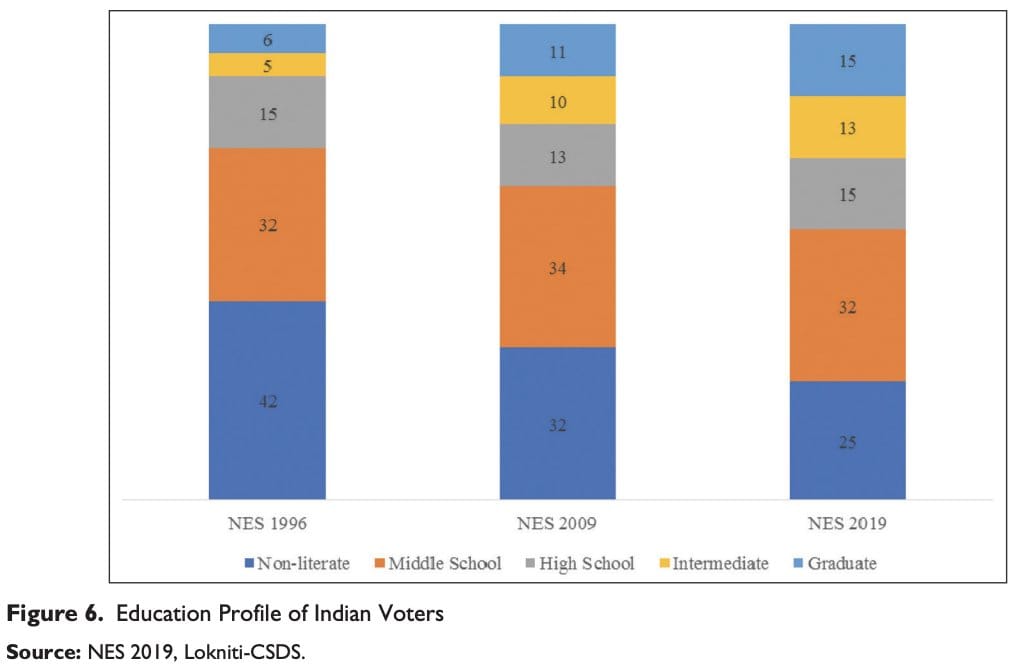

Indians are more educated (Figure 6) and more exposed to media (especially internet-based news platforms and social media). These demographic changes have not only altered the ‘catchment area’ for the BJP voters, they represent an ideological detachment from the politics of recognition (caste and religious politics as conventionally understood) and statism (statist solutions to social and economic norms) among BJP voters.

Is the expansion of the Hindu middle class linked to increased ethno-political majoritarianism? So far, our understanding is based on the idea that majoritarian world-view in India emanates from Hindu nationalistic sentiments (and Hindu religious practices). While some may argue that these two indices—ethno-political majoritarianism and Hindu nationalism—may be capturing the same underlying phenomenon, the data presented challenge this assumption. It also forces us to re-think the empirical basis behind these conceptual formulations.

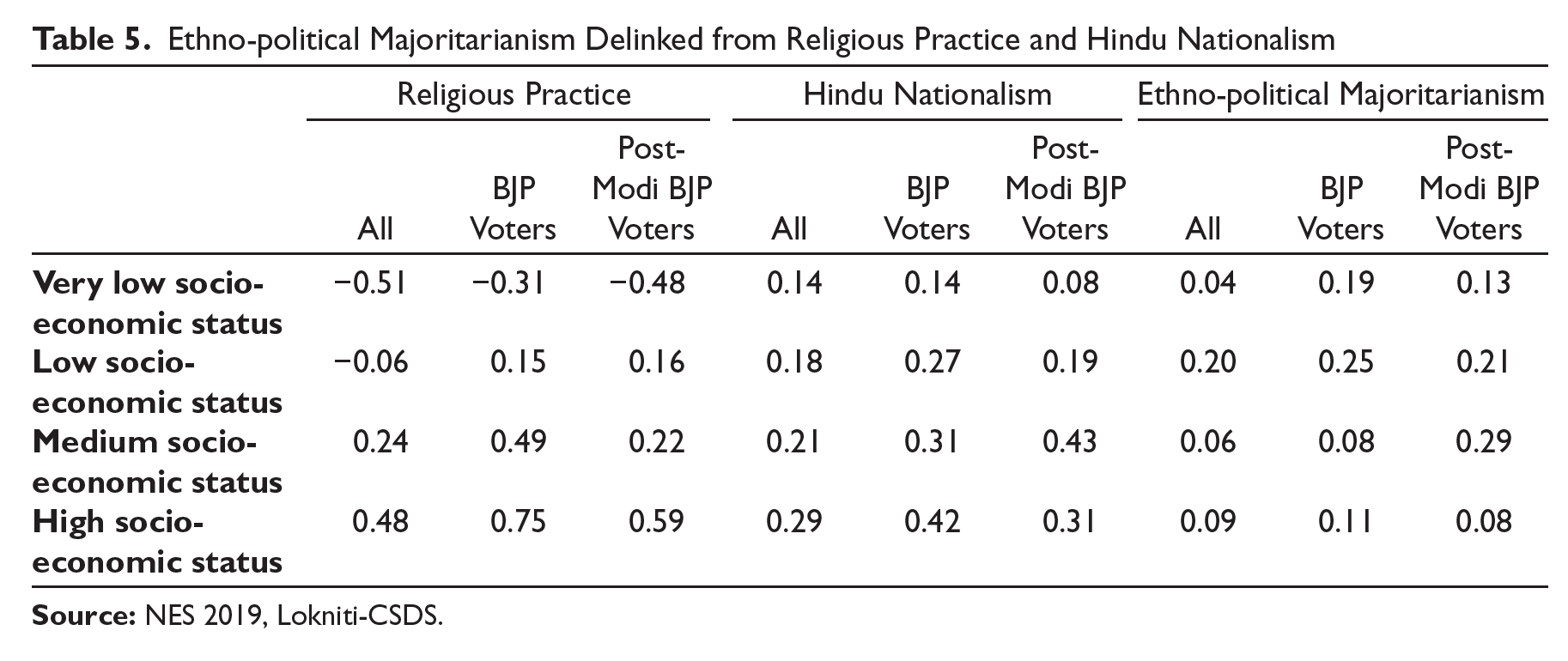

The NES 2019 provides some preliminary evidence for the delinking of ethno-political majoritarianism from Hindu nationalistic sentiment, which mostly resonated with upper-caste sensibilities. While these conceptual categories may have overlapped in the past (often described as Hindutva), the bottom rung of Hindu society is less likely to be enamoured by a political ideology of Hindutva that is tied to upper-caste sensibilities. The data presented in Table 5 show that, while religious practice and Hindu nationalism are greater among the members of higher socioeconomic status, ethno-political majoritarianism is maximum among the middle ranks. This pattern holds not only for all respondents but also for those who voted for the BJP and even for new BJP voters.

Also read: Four reasons why BJP is losing to Congress and regional parties in assembly elections

Conclusion

The BJP’s victory in 2019 was not just due to the immediate context preceding the elections, but also to the structural shifts taking place in Indian politics and society. The success of the BJP in 2019 is indeed tied to the personal appeal of Narendra Modi and the general disarray among the opposition. But, in our view, the real implication of the 2019 election is that the fourth party system, this time anchored around the BJP, is here to stay.

The BJP has expanded its geographic reach and broadened its social coalition. While it has brought politicians from other parties into its fold, the BJP has also expanded its influence because of the greater acceptability of its ideological messages, especially among the middle-class Hindus. The BJP’s new social coalition is driven less by malleable factors such as leadership and reconvening welfare benefits, and more due to structural shifts. Thus, it appears that this coalition is stable for the foreseeable future as far as national elections are concerned.

Pradeep Chhibber is Professor and Indo-American Community Chair in India Studies at UC Berkeley, US. Rahul Verma is a Fellow at the Centre for Policy Research. Views are personal.

This is an edited extract from the authors’ paper ‘The Rise of the Second Dominant Party System in India: BJP’s New Social Coalition in 2019‘, which was published in Sage Journals. Read the full paper here.

All these surveys and studies can go ashtray,if, only if, congress can hire a man with political brain. All these bjp leaders and it cell and their pet media don’t have very high IQ. they’re just lucky. Anyone can turn this whole thing on their head. given the right one gets a chance.

A party that rules 40% of the regions in India does not get such undeserved praise.

More than 50 now