When the Waqf Amendment Bill 2024 was first tabled in the Lok Sabha on 8 August last year, it triggered fears within the Muslim community, as it was perceived to have been introduced without adequate consultation with stakeholders. After all, the issue of waqfs— Muslim institutions through which property is bequeathed for religious or charitable purposes—is sensitive because it involves socio-religious spaces such as qabristans, masjids, idgahs, and madrasas.

As such, the government and Parliament were exhorted to adopt procedures that allayed rather than stoked the fears of Muslims. In this backdrop, the decision to refer the bill to a joint committee of both Houses of Parliament was welcome. The 31-member committee, drawn from across party lines, received 97,27,772 memoranda overall. There were representations from various ministries and departments—including Minority Affairs, Law and Justice, Railways, Housing and Urban Affairs, Road Transport, and Culture (Archaeological Survey of India)—as well as state waqf boards and experts, ensuring a diversity of opinions.

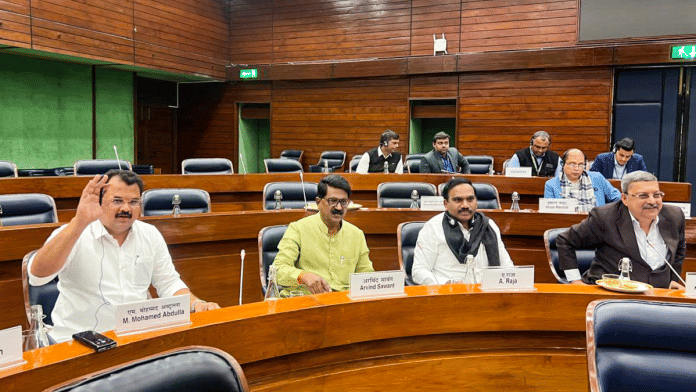

However, the acrimonious divisions between government and Opposition benches during the 13 February tabling of the parliamentary committee report are disconcerting. They imperil the opportunity for an objective and informed debate on a national issue, the significance of which transcends any single community.

Broadly speaking, there are two divergent viewpoints on waqf reforms. On one hand, the government views the reforms as essential for improving the administration and management of waqf properties in India. Its proposed measures include updating the definition of waqf, improving the registration process, and increasing the role of technology in managing waqf records. On the other hand, the Opposition alleges that these proposed changes could undermine the cultural and religious rights of the Muslim minority.

As we expect Parliament to take up the report in the near future, I analyse some of the contentious issues surrounding the waqf reforms.

Also Read: Here’s what JPC report on Waqf Bill redacted from Opposition’s dissent notes

Calls from within the community

It is not entirely correct to state that waqf reforms are being externally foisted. Rather, to a large extent, the demand for waqf reforms has emerged from within the Muslim community also.

The Ministry of Minority Affairs received numerous complaints from Muslims on the maladministration of waqf properties, which manifested in voluminous litigations. The ministry’s analysis of grievances received from April 2023 found that 148 complaints pertained mostly to encroachments, illegal sales of waqf land, delays in surveys and registration, and complaints against waqf boards and mutawallis (property caretakers). Data from the Centralised Public Grievance Redress and Monitoring System (CPGRAMS) from April 2022 to March 2023 further reveals that out of 566 complaints received, 194 related to illegal encroachment and transfer of waqf land, while 93 were against waqf officials and mutawallis.

Moreover, an appraisal of the functioning of waqf tribunals reveals that 40,951 cases are currently pending, of which 9,942 have been filed by Muslims themselves against institutions managing waqfs. In addition, there are inordinate delays in the disposal of cases, and there’s no provision for judicial oversight of tribunal decisions.

Over the years, a number of issues pertaining to mismanagement have come to the fore—delays in registration of waqf properties, waqf boards fetching rents below market value, rampant encroachments on waqf land, denial of inheritance rights of widows, non-completion of surveys by survey commissioners, and slow progress in digitisation of waqf property records. Many such issues have been extensively reported in the media from time to time.

Also Read: Waqf is anti-Quran. Muslim elite used it to build political power

Inclusion, diversity, and community character

The proposed reforms also contemplate representation for underrepresented and deprived Muslim groups, including women and Pasmandas. The idea is to make state waqf boards and the Central Waqf Council more diverse and inclusive. Not only will such a measure lead to sociological diversity and gender balance within these institutions, it could also reshape the political interaction of the Muslims with the BJP.

Further, the proposal to include non-Muslim members who bring technical expertise in waqf administration should not trigger anxiety within the community, provided such representation does not erode the community’s primacy in administration.

Rather, leveraging cross-community expertise and efficient technology in effecting a scientific process to manage waqf properties has the potential to transform waqf institutions into inclusively governed national resources. After all, waqf boards are India’s largest landowners after Defence and Railways, holding approximately 8 lakh acres of land with an estimated value of about Rs 1.2 lakh crore.

The view that waqfs have a ‘public’ character is evidenced by the fact that many Islamic nations—including Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Kuwait, Oman, Bangladesh, and Turkey—have state-regulated legal frameworks for waqf administration. In fact, some Islamic nations do not have waqf institutions at all.

It is rather unfortunate that acrimonious divisions within the parliamentary committee marred the tabling of the report in Parliament. While a certain degree of politicisation is natural in a parliamentary democracy during any law-making exercise, the underlying values of non-partisan deliberation, consensus-building, and effective communication between ruling and Opposition parties are essential for advancing the national interest. As such, these values must inform the future parliamentary course of action on the waqf reforms.

The writer is a Nominated Member of the Uttar Pradesh Legislative Council and former Vice-Chancellor, Aligarh Muslim University. He posts on X @ProfTariqManso1. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)