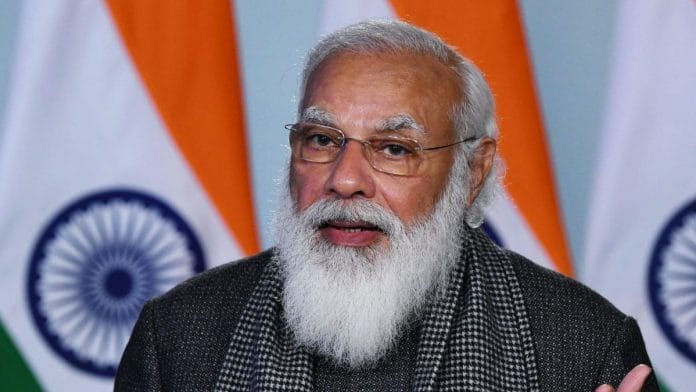

One of Narendra Modi’s first promises when elected India’s prime minister in 2014 was to revive the country’s manufacturing sector. India had been de-industrializing since the early part of the century and policy makers correctly argued that only mass manufacturing could create enough jobs for a workforce growing by a million young people a month.

In his first major speech as prime minister, Modi invited the world to help: “I want to appeal all the people world over [sic], ‘Come, make in India,’ ‘Come, manufacture in India.’ Sell in any country of the world but manufacture here.”

The “Make in India” slogan quickly developed into a full-fledged government program, complete with a snazzy symbol — a striding lion made out of meshed gears. Government officials spoke at length about increasing foreign direct investment and improving the business climate to attract multinational companies. Careful targeting of the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business indicators raised the country 79 positions in the five years after Modi took office.

And, after all that, in 2019 the share of manufacturing in India’s GDP stood at a 20-year low. Most foreign investment has poured into service sectors such as retail, software and telecommunications. “Make in India” has failed, replaced by a government that never admits defeat with a call for “self-reliance.”

Now, exactly 30 years after India turned away from central planning and liberated the private sector, the government is again handing out subsidies and licenses while putting up tariff walls. Modi shut down the 1950s-era Planning Commission when he took office. Yet the bureaucrats in New Delhi are back to picking winners and directing state funding to favored sectors.

They’re doing so through new “production-linked incentive” schemes, in which companies apply for and receive extra funding from the state for five years in return for expanding manufacturing in India. Such incentives were originally meant to support domestic mobile-phone production. Following energetic lobbying, the government began extending them blindly to all sorts of sectors, from batteries to food processing to textiles to specialty steel.

Money is apparently no object: A government that has held off on income support during the pandemic has budgeted Rs. 2 trillion (roughly $27 billion) for these industrial subsidies.

The only thing worse than socialism with central planning is industrial policy with no planning at all. There’s no logical coherence to the sectors chosen, all of which seem to have been included for different reasons.

Is the scheme supposed to supercharge job growth? Then why not focus on labor-intensive sectors such as apparel? Is India aiming for economic independence from China? Then subsidies should be limited to sectors where China dominates supply chains, as part of a broader, China-focused trade policy that partners with the United States, Australia and others. Is the goal to invest in cutting-edge sectors? Then the government should explain why bureaucrats would do a better job than the flood of private equity that’s pouring into India.

Instead, all the problems of India’s socialist-era past are returning, cunningly disguised. Excessive closeness between bureaucrats and the beneficiaries of industrial policy? India’s top civil servant recently called for an “institutional mechanism” that provides “hand-holding” for companies. Endlessly shifting targets? Companies that just began receiving subsidies are already asking the government to relax production quotas.

It took decades for India to put its old, inward-looking and uncompetitive manufacturers out of business. Now the government is giving cash to new, inward-looking and uncompetitive companies to produce for the domestic market. Meanwhile, it’s hard-wiring into the economy the kind of connections between industrial capital and policy makers that are nearly impossible to disentangle.

The government’s defenders point out that its investor-friendly reforms weren’t answered; nobody came to “Make in India.” And, they ask, hasn’t China profited handsomely from subsidizing its own manufacturing sector?

Such arguments miss the point. Modi’s manufacturing push never went much further than gaming the World Bank’s indicators. No investor believes structural reforms, particularly to the legal system, have gone deep enough. India has a large workforce but too few skilled workers. To top it all off, the rupee is overvalued. Rather than work at solving these interconnected and complex problems, politicians in New Delhi have decided to paper over them with taxpayer money.

Perhaps picking winners has worked for China. What Indians know for certain is that it did not work here after decades of trying. Sure, public investment in sectors of vital strategic importance — electricity storage, perhaps, or cutting-edge pharma — is defensible. But when you start throwing money at every sector that you wish had developed on its own, then all you’re announcing to the world is that you’re out of ideas.

India’s haphazard foray into industrial policy is going to fail, just as “Make in India” did. And it’s likely to cost the country billions along the way.- Bloomberg

Also read: India needed a crisis to reform. It got one in 1991, thanks to Nehru & Indira’s Soviet model