The Ministry of Corporate Affairs recently expanded the application of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code to include non-banking financial service providers. It will help inject new capital into the industry and potentially salvage some failing non-banking financial companies. But with the National Company Law Tribunal already clogged up, adding NBFC cases will further reduce the effectiveness of the whole insolvency process.

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code or IBC was enacted in 2016 to battle India’s non-performing assets (NPAs), and the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) was set up as a dedicated bench to handle these cases. The IBC and NCLT are currently under-performing. Including some financial service providers (FSPs) within the IBC could overload the already heavily-burdened process. India’s financial firms need a separate resolution authority altogether, with a sharper focus and technical expertise.

Overburdened NCLTs

The Ministry of Corporate Affairs recently issued two notifications to enable the handling of some types of FSPs. On 15 November 2019, it enacted the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Rules, 2019 to include financial service providers. A second notification on 18 November allowed non-banking financial companies (NBFCs) with assets worth Rs 500 crore or more to file for resolution under the IBC.

Until now, the NBFCs did not have a specific provision for resolution of stressed assets. New management could not take over and revive the NBFCs. As a result, the alternative banking industry kept ballooning, damaging the entire financial sector.

Currently, the NCLT hears all cases related to corporate disputes, not just insolvency and bankruptcy cases. In addition to this, it also hears real estate cases, which could have been referred to the Real Estate Regulatory Authority (RERA).

Between its inception in 2016 and 20 September 2019, the NCLT has initiated the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) for 115 cases in the real estate sector; 87 out of these are currently ongoing. This is not counting the number of cases that were not even admitted to the CIRP. Recently, banks were given discretion to refer cases to the NCLT on a case-by-case basis. The lack of an outside restructuring procedure is further increasing the burden on NCLTs.

Also read: Why Essar Steel insolvency case is back in Supreme Court, mocking hope of swift resolution

Need separate mechanism for NBFCs

The best outcome of an insolvency/bankruptcy process is resolution or restructuring or sale, as opposed to outright liquidation. This ensures the entity does not lose value, and more competitive promoters can potentially take over. Although the fear of liquidation helps keep unscrupulous promoters on their toes, liquidation remains the worst possible outcome.

Of the total 2,542 cases admitted for CIRP, only 156 have been closed through resolution, while 587 were recommended for liquidation; nearly 59 per cent of the total cases are still ongoing. Total recovery of assets is touted at 43 per cent, but this includes seven of the 12 big accounts that make up a bulk of the corporate defaults. If we leave out these seven accounts, the recovery rate is only 30.4 per cent, not too different from the earlier recovery rate of 27 per cent before the IBC was enacted.

Considering the delay in other ongoing cases in the NCLT, the NBFCs require a separate mechanism for handling bankruptcy.

A hasty measure won’t help

The lack of a separate apparatus for the NBFCs also glosses over some structural issues, which will arise once the NCLT mechanism is used for their resolution.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), as the financial regulator, seems to be holding all the power, from initiating the insolvency process to its resolution, thwarting any headway that an insolvency resolution professional (IRP) may make with regard to turning around assets.

This also means that no one, not even depositors, can initiate the process except RBI. Further, ambiguity remains on the fate of depositors’ assets, although the regulator, again, has the final say. The NCLT has inadequate administrative, technical and judicial staff, and things may take a turn for the worse if the case-load increases.

Therefore, the suggested measure, while being temporary, also leaves much to the imagination about the future of FSP bankruptcy. With bank runs still a problem in India, a gap remains as banks are excluded from the process.

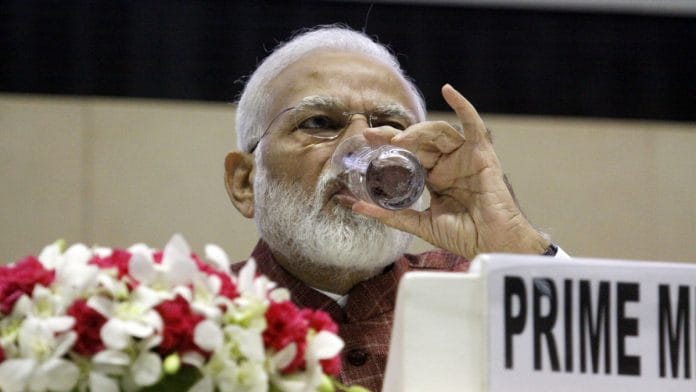

The new notifications on FSPs and NBFCs to seek bankruptcy resolution is a welcome step. However, with the NCLT already experiencing back-logs, this hasty measure is insufficient. The need of the hour is a full-fledged Financial Resolution Authority, which the Narendra Modi government had considered in its first term.

Also read: SC upholds IBC amendment, allows home buyers more remedies against defaulting developers

The author is a research associate for the Wadhwani Chair in US-India Policy Studies, where she specialises in US-India economic ties and Indian federal economic reforms. Views are personal.

The half cooked information in the article leaves the readers more confusion than ever. While judging upon the efficacy of IBC by saying that the recovery rate is only 30.4 per cent which is not too different from the earlier recovery rate of 27 per cent before the IBC was enacted, the article has ignored the MOST IMPORTANT factor – TIME INVOLVED IN RESOLUTION. The entire perspective of writing the article goes for a toss if the writer cant understand the TIME VALUE OF MONEY.

Come on! What is the remedy you suggest. Exclude NBFCs from Bankruptcy Code? Failure of financial institutions is reaching dangerous proportions in India. Government will set up more benches of NCLT if need be, inasmuch as Bankruptcy code prescribes a time bound proceeding. NBFC cannot drag their feet as they do in other courts.