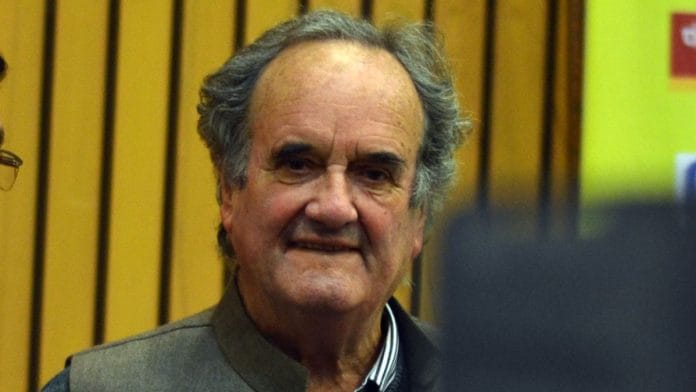

I have written recently, criticising and lampooning the BBC. And one of the reasons I did so was because I belong to that generation of Indians who remain nostalgic and sentimental about the “old BBC”. And no one represented the old BBC better than Mark Tully or ‘Tully Sahib’ as he was popularly known.

I had the good luck of meeting Tully once in Bengaluru. I introduced myself and told him about being a big fan of his. His responses were courteous, modest and most unassuming. We talked about and around the subject of Operation Blue Star. He refused to lay claim to special insights and left me with a hint that it was not sufficient to stay focused on India’s crises; it was necessary to spend time contemplating India’s unlikely successes. For an impatient cynic like me, it was a fairly compelling warning.

Tully was a child of the Raj born in pre-1947, racially segregated Calcutta. An English nanny, boarding school in Darjeeling, public schools in England and Cambridge University were the settings of his childhood and youth. Difficult as it is to believe, at one time, Tully wanted to become a Christian priest. His entry into the BBC was almost a matter of chance, as was his assignment to India. Of course, we in India know better. It was not chance. It was ‘karma’. Tully was karmically connected to India from previous lives. And that connection was overwhelming in his most recent life.

When we take a critical look at a person’s writing, we are expected to indulge in “analysis and comparison”. At least that is what Mathew Arnold suggested, and TS Eliot endorsed.

When you “analyse” Tully’s writings, some things stand out. He wrote not for an English audience, but for an audience of Indians and perhaps some in the West who may have a passing interest in Indian things. He liked rural and small-town Indians. He was deeply suspicious of urban sophisticates. That is perhaps why he never fell into the honeyed traps set by Indian leftists, which has been the downfall of today’s BBC journalists.

Also read: From the Bangladesh War to the Babri demolition—it wasn’t news until Mark Tully aired it

Mark Tully’s writings

Tully hated the Indian bureaucracy. Obviously, he had reasons based on personal experience. Don’t we all have more than adequate reasons? There was also a strand of guilt because at the back of his mind was the persistent feeling that India’s current bureaucratic horrors are directly linked to the legacy of the Raj, for which Tully assumed a responsibility which was not at all necessary or obvious in this writer’s opinion. Tully’s prose style was simple and to the point. None of the effete pomposity of an E M Forster.

When one “compares” Tully’s writings with Philip Mason/Woodruff and Charles Allen, one gets to see the important discontinuity. The other two wrote primarily about the India of the Raj. Tully wrote primarily about post-Raj India. But there is more than that. Mason/Woodruff “loved” a fantasised India and was pointedly defensive about its “guardians”, the word he liked when referring to the British rulers in India. Allen was also associated with the BBC. But he preferred to focus on the past, and while he was more sympathetic to Indians than Mason/Woodruff, he too suffered from a patronising superciliousness about the India he claimed to love.

Tully relentlessly focused on the present, and he treated Indians not as distant objects but as subjects with agency. He was also able to effortlessly collaborate with Indians like Satish Jacob and Zareer Masani, with whom he co-authored books. On balance, while Mason and Allen may have written more and may still be referred to by history students, it is Tully who has left behind some of the best prose on the palimpsest and tapestry which has been ‘the India’ after 1947.

Everybody knows the story of Rajiv Gandhi insisting on checking the veracity of his mother’s death with Tully at the BBC. What many may not know is that Tully’s coverage, thoughtful analysis and journalistic nuggets about Operation Blue Star and about the Bhopal Gas Tragedy remain to this day definitive, empathetic, impartial and almost conclusive.

Tully left the BBC long ago, largely on account of the intolerance that had crept into that over-bureaucratised organisation. Unfortunately, he lived long enough to witness the BBC turn into a vicious anti-India outfit and to repeatedly shame and humiliate itself in world circles. Never mind. Tully lives on, and his olde BBC lives on as the friend of India even as ‘Tully Sahib’ probed, engaged, criticised, analysed and endorsed what was in effect his India. We all loved you for it, and we will remember you and honour you for it.

Jaithirth ‘Jerry’ Rao is a retired entrepreneur who lives in Lonavala. He has published three books: ‘Notes from an Indian Conservative’, ‘The Indian Conservative’, and ‘Economist Gandhi’. Views are personal.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)