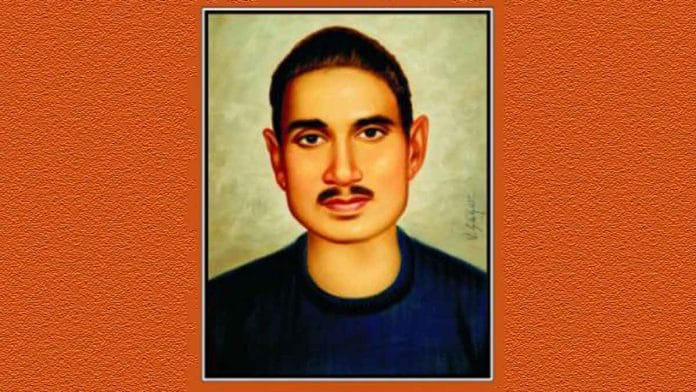

The first publisher of Periyar’s work in Hindi who also fought in the Indian Supreme Court against its ban should by now be a social justice celebrity. But Lalai Singh is not a name that people recognise or talk about.

The reason for his near-oblivion is also the reason why Periyar isn’t popular in North India.

Lalai Singh (1911-1993) remained a nondescript personality even in the Hindi public sphere, despite publishing Periyar’s Ramayana: A True Reading in 1968. The following year, the Uttar Pradesh government banned the book. Lalai Singh fought the case in the Supreme Court and the three-judge Bench of Justice V.R. Krishnaiyer, Justice P.N. Bhagwati, and Justice Syed Murtaza Fazalali ruled in his favour.

In 1935, Lalai Singh joined the Gwalior National Army as a constable and retired from the force in 1950. He devoted his life to the Ambedkarite-Rationalist movement and published scores of books and pamphlets. He wrote popular plays on Rishi Shambuka and Ekalavya and provided alternate subaltern readings of myths and mythologies. He joined Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s Republican Party of India (RPI) and played a role in creating the ideological infrastructure, based on which Kanshiram mobilised Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Other Backward Classes (OBCs). Young researcher Dharmveer Yadav Gagan has compiled Lalai Singh’s writings and speeches in five volumes.

It’s interesting that despite the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) becoming a formidable force in Uttar Pradesh and forming the government on four occasions, Lalai Singh’s stature in Bhaujan politics never grew. His ideological guru, Periyar, was also never celebrated as a Bahujan icon by the Uttar Pradesh government.

So why was Lalai Singh sidelined in the Bahujan-social justice discourse? And why did Periyar never attain South India-like stature in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, states that witnessed the ‘silent revolution’ in the 1990s?

Also read: Why Bengal and North India failed to produce any Phule, Ambedkar, Periyar

Periyar and North India

Periyar’s work can be understood using the metrics of federalism, anti-Congressism, struggle against the forceful imposition of Hindi, rationalism/anti-Brahminism, social justice and women’s rights among others. The north Indian social justice movement had a different frame and trajectory in which Periyar and Lalai Singh don’t fit.

Lohia and other socialists led the political assertion of farmer communities and OBCs who were marginalised and sidelined in the Congress-led politics in North India.

This movement led to many political processes including the emergence of a galaxy of OBC/farmer leaders like Mulayam Singh Yadav, Lalu Yadav, Nitish Kumar, and Sharad Yadav among others. Christophe Jaffrelot empirically argues that during this period, the number of OBC legislators increased in Parliament and state assemblies.

But Lohia and OBC politics per se was not influenced by south Indian social reform movements. It was more about claiming their share in power politics and other spheres. This politics never tried to elevate the consciousness of the toiling masses. Ideas like rationalism and scientific temper were never part of the agenda of Lohia and his disciples. Even the idea of social justice was reduced to political participation and reservation in government jobs and education. Lohia descended to the level of ordinary masses and organised Ramayana Mela. Mulayam Singh and Lalu Yadav never endorsed atheism and anti-Brahminism and Periyar was of no use to them.

Kanshiram’s BSP did include Periyar in its early publicity materials and banners and posters. It can be said that Kanshiram introduced Periyar to the villages and towns of north India. The BSP would organise large-scale Periyar Melas (Periyar Festivals) where ideas like social empowerment, social justice and anti-Brahminism would be discussed. But the compulsion of electoral politics and an alliance with the BJP forced it to act differently. Periyar Mela soon became the bone of contention until the BSP eventually stopped organising them. Due to BJP’s protest, the BSP also shelved its plan to install a statue of Periyar at Ambedkar Udyan in Lucknow in 2002. As per media reports, Mayawati denied there was ever such a proposal. “The Dalit saint has a following in South India. If a statue is to be installed, it would be somewhere in that part,” she had reportedly said then. Soon, Periyar pretty much vanished from the public discourse in Uttar Pradesh. Later, as the BSP opted for Sarvajan politics and Bhaichara Sammelans, Periyar became a complete no-go area for the party.

Bihar proved to be more barren in terms of inculcating Periyarist thoughts. The BSP never flourished in Bihar and there was no Lalai Singh or RPI to propagate Periyar’s thoughts. Social justice in Bihar was limited to Lohia socialism and lower and middle-caste representation or reservation in government jobs. In other Hindi heartland states like Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, political power largely remained in the hands of Congress and Jana Sangh/BJP. These three states never became fertile ground for the Socialist Party or the BSP.

Periyar had very strong views on culture and language and that was a corollary to his idea of federalism. Hindi imposition by the Union government was a fact and Periyar understood the perils of the Centre’s language policy. But his democratic, anti-hegemonic ideas were projected as anti-Hindi rhetoric to North Indians. This limited his capacity to expand his influence beyond the boundaries of Tamil Nadu. An anti-God, anti-Brahminism, Anti-Hindi ideologue Periyar found no takers in the north. His disciple Lalai Sigh suffered the same fate.

Another reason for Periyar not finding political takers in the north can be the unique Hindu social structure of North India. Unlike Tamil Nadu, where it was easy to harp on Brahmin and non-Brahmin binary, the north Indian Hindu social structure has a large population of intermediate castes. For the subalterns, it is not always some Brahmin doing the oppression. The language of anti-Brahminism does not have universal appeal among the OBCs and SCs in the north. On this count, Periyar’s language proved to be a misfit in the north Indian scenario.

Dilip Mandal is the former managing editor of India Today Hindi Magazine and has authored books on media and sociology. He tweets @Profdilipmandal. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)