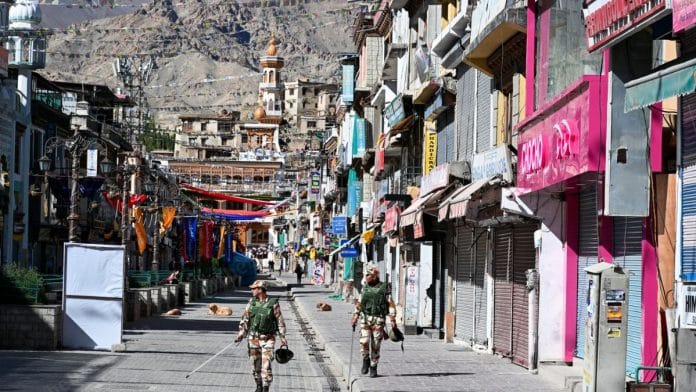

The Modi government is back to its usual playbook, blaming external forces and the Congress party to deflect attention from the fact that the Ladakh crisis is of its own making. The home ministry’s control freakery, unfulfilled promises, and rising unemployment have united Buddhist-majority Leh and Shia-majority Kargil in a movement for greater political and cultural rights.

It is clear that India’s relationships with the new regimes in neighbouring countries such as Bangladesh and Nepal have become more strained or uncertain. Also clear is the fact that India was effectively fighting both China and Pakistan during Operation Sindoor. In such a situation, it is utter folly to alienate key border regions like Ladakh and Manipur. But that’s exactly what Amit Shah, the so-called second coming of Sardar Patel, has managed to do.

Just look at the government’s high-handedness. It has unleashed its full authoritarian might on Sonam Wangchuk, arresting him under the National Security Act. Yes, there should be a proper investigation into his role in the 24 September Leh riot. But compare this with the treatment of the BJP’s Kapil Mishra. On the eve of the Delhi riots, in which 53 people were killed, Mishra openly threatened violence against Citizenship Amendment Act protesters. Rather than being arrested, he went on to become—believe it or not—Delhi’s Minister of Law and Justice.

Broken promises

When Article 370 was abrogated and Ladakh was carved out of Jammu and Kashmir as a separate Union Territory (UT), the Buddhist-majority population of Leh celebrated. However, the Shia-majority region of Kargil, more closely connected to Kashmir, was unhappy. Leh had demanded UT status for decades, a dream that seemed to have come true.

However, Leh’s early optimism about being freed from a domineering Kashmir soon faded. Residents realised that their future would now be decided by an unelected Lieutenant Governor and distant civil servants, rather than the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Councils in Kargil and Leh, which control only 5-6 per cent of the UT’s budget.

In Jammu and Kashmir, the government had at least assured the Supreme Court that statehood would be restored “at an appropriate time”. It followed through by holding Assembly elections in September-October 2024, which produced a National Conference-led government. But Solicitor General Tushar Mehta told the Supreme Court: “So far as Ladakh is concerned, its UT status is going to remain for some time”. There could not have been a clearer message for Ladakh.

Consider the main demands of the agitation:

- Statehood for Ladakh

- Inclusion in the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution

- Job reservations for residents

- A Ladakh public service commission for government jobs

- Two parliamentary seats, one each for Leh and Ladakh

The main argument is that Ladakh—with its distinct culture, fragile ecology, and predominantly tribal population—should have the authority to make its own decisions on matters such as land, water, health, sanitation, and culture, much like the autonomy granted to tribal areas in many northeastern states by the Sixth Schedule. Instead, the removal of Article 370 and Article 35A in 2019 has opened the region to an influx of outsiders, raising concerns that Ladakh may face the same harmful consequences of unregulated development that have affected other small hill states.

Joblessness is rampant, with the unemployment rate for graduate youth at 26.5 per cent in 2022-23. In July, there were 50,000 applications for 534 vacancies advertised by the Subordinate Services Recruitment Board in Leh.

Although the Sixth Schedule technically applies only to northeastern states, on 11 September 2019, the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes recommended Ladakh’s inclusion as a tribal area under it. The move received “no objection” from the Ministries of Home Affairs, Tribal Affairs, and Law and Justice. Moreover, in its 2020 hill councils election manifesto, the BJP promised to include Ladakh in the Sixth Schedule “to protect the land, jobs, and environment” of the region.

The Modi government’s belated concessions don’t address the movement’s core demands.

Also read: UNGA was Nepal’s missed opportunity. It can’t ignore foreign policy during domestic turmoil

The way forward

So what’s the problem? In a word: China. With a military buildup in eastern Ladakh and heavy investments in roads, tunnels, and solar power, the government presumably believes that greater devolution could interfere with strategic objectives and military flexibility.

However, the reasoning is flawed. It should be obvious that an alienated population poses a far greater threat than the need to secure local approval for land acquisition or infrastructure projects. Not to mention the fact that Leh and Kargil have stood with India through repeated wars and conflicts. Moreover, the Sixth Schedule is flexible enough to exclude border tracts and militarily sensitive areas.

To find a real solution, the Modi government will have to go against its deepest instincts. It will have to treat ethnic and religious minorities with equal respect and learn to devolve power to the people. And realise that mindless centralisation does not strengthen the country, but renders it brittle.

Amitabh Dubey is a Congress member. He tweets @dubeyamitabh. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)

Many thoughtful observers are drawing a worried parallel between Ladakh and Manipur.