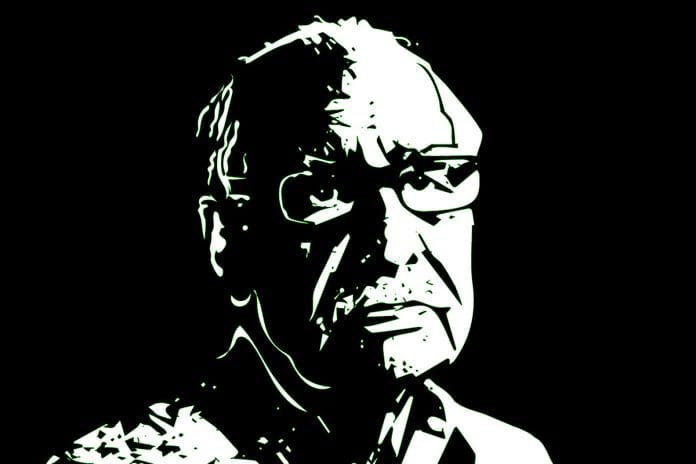

India’s greatest “scoop-man” often regretted that the title of Editor eluded him. But he more than made up for that in fame as a columnist, diplomat, MP and peace activist.

Earlier this week, The New York Times surprised its readers, and shocked us reporters’ community by dropping its reporters’ bylines on stories featured on its home page. The following day, its editors came up with the reasoning: Many more readers now access the newspaper on their mobiles than the desktop. We adore our reporters, but their byline on top of the summary isn’t the best way to display a story digitally. Good point, you might have said. But only if you missed the fact that the op-ed writers’ bylines are there as before.

We bring this up in this tribute to Late Kuldip Nayar, because reporter/newsgatherer versus the editorialist is the oldest power tussle in the newsroom. The latter, with their superior intellect, weighty arguments, and fine turn of phrase have mostly won it. Their domination was total in India, until Nayar broke it in 1970-80.

Also read: ‘Hurts to see journalists bending backwards to remain handmaidens of proprietors, govt’

He was Indian journalism’s first rock star in an era when any editor would have taken umbrage at being described as such. Nayar’s rise as India’s pre-eminent byline came when there was no news TV, glossy magazine profiles, and three decades before Twitter. And for my journalism school, in the prison and out of it that year, Nayar’s was the most inspirational story. More stirring than even the then recent Bob Woodward, Carl Bernstein and the Watergate expose.

He is India’s greatest “scoop-man” ever, our teacher, late Prof. B.S Thakur, would say to his students, most of whom had strayed into his journalism class for failing to get into something more worthwhile, to teach them that “scoop” also meant something even sweeter than a mere dollop of ice cream. There were classroom debates on what the Emergency meant for the press (nobody said ‘media’ then) and especially for our employment prospects. The entire Indian press had caved in, but some had shown that a fight-back was possible. After all, Nayar had even gone to jail.

The end of the Emergency began the first golden era of Indian journalism. Pre-censorship had sensitised the people to the value of a free press. If The Indian Express was the Emergency’s shining star, Nayar was its face. Never mind that in the Express’s formidable editorial star-cast, he featured third, after Editor-in-Chief S. Mulgaonkar and Editor, Ajit Bhattacharjea. Nayar was Editor, Express News Service. But he was the paper’s real masthead. His earlier books, Between The Lines, India: The Critical Years, Distant Neighbour had also brought him greater intellectual heft than those above him, “in spite of being a mere reporter”.

His presence in the newsroom was electric and his network of contacts the stuff of legends. “Arrey kya, George (Fernandes), why are you bent on breaking the (Janata) Party,” you’d overhear him admonishing the great Socialist. Or, “Hello, Idris, (Air Chief Marshal, Idris Hassan Latif), I hope you and Bilquees know Chandigarh is such a boring place.” Later, around midnight, he walked in to give Mrs Latif a post-prandial tour of the newsroom and its hot-metal press underneath. His human rights/civil liberties phase also began in these heady months. He was a member of the Justice V.M. Tarkunde Committee probing the killings of Naxalites in fake encounters.

The best and the fairest tribute to Nayar would be that he made the reporter the prince of the Indian newsroom. The Indian Express itself produced a stellar team of young reporters under him, many of who rose to editorships later. Three other young editors who emerged in that era, Arun Shourie, Aroon Purie and M.J. Akbar then made Nayar’s reporter-prince the king.

Ramnath Goenka had a great eye for editorial talent. He brought Shourie into journalism from scholarly activism, as Executive Editor in 1979. Suddenly, from number 3, Nayar was 4, despite his stardom. More importantly, Shourie was more accessible, less distracted, brimming with new ideas and energy. Younger reporters gravitated toward him. Goenka wanted to modernise his paper. He saw Shourie, 37, as the man for it, not Nayar at 57. Plus, as is often the case with owners, he wasn’t particularly impressed, but impatient with Nayar’s new fame. Soon enough, all of other editors were sidelined and some, including Nayar, were let go. It’s a different matter that within three years Goenka developed insecurities with Shourie as well and dismissed him peremptorily. Several of us reporters too left in Shourie’s wake.

Nayar returned to the newsroom in the summer of 2014 “for the first time after 1980” (1981, actually) for a conversation with the editorial team while promoting his memoir Beyond The Lines. He began that conversation by ruing that he had been fired by Goenka because Indira returned to power in 1980 and he wanted to make peace with her by sacrificing him. This part of the recording has been re-published by the paper with its report on his passing away. This was untrue. It simply isn’t in that paper’s DNA to fire editors to please governments. Some of us did, respectfully, say this to Nayar.

Nayar also said, in the same recorded chat, that he regretted that “nobody offered me any job after 1980”. It rankled with him. As did the fact that many who worked at entry levels under him, and who he believed were way lesser journalists than him, rose to be editors of newspapers, a title that eluded him, although he had been editor of the Delhi edition of The Statesman. He had the innocence and honesty to say this often to many of us. He later became High Commissioner in London, a Rajya Sabha member, but all this new eminence wouldn’t compensate for the title he had missed. The Express did make it up to him, at least symbolically by conferring the Ramnath Goenka Lifetime Achievement Award to him in 2015.

What he missed by way of an editorial title, Nayar more than made up in fame, both as a columnist and subcontinental peace activist. Critics joked about him being the ‘neta’ of the ‘mombatti’ (candle-light marchers at Wagah) gang. But he was unfazed in his commitment to an Indo-Pak rapprochement. This peace-making, after diplomacy and Parliament became his new calling and took him away too early in his career from the kind of journalism he was best at. He was indeed never offered a job after 1980, but it isn’t because he had become unemployable. He had chosen a more varied life and excelled in it.

Also read: The India-Pakistan border haunted journalist Kuldip Nayar all his life after Partition

From the parochial point of view of us reporters, it is a loss that he gave up so soon. Or he would have risen as India’s finest reporter-editor and its most influential and insightful columnist too. Today’s generation of reporters could’ve done with a figure like him, just when the trend of reporter-editors that he pioneered is being reversed in India with owners either becoming editors themselves, or preferring diligent, sharp but non-threatening back-room choices. Or when the venerable New York Times junks its reporters’ bylines from its home page, while retaining the columnists’. As that eternal newsroom tussle is again being lost by us, we will greatly miss Nayar for the reporter-editor he was and equally rue that he was denied what he could have been.

Postscript: Kuldip Nayar gave me three important counsels often. The first, that I must begin and sustain a weekly column, I dutifully followed. That is how ‘National Interest’ came about. Second, that I must have an afternoon nap, I try occasionally, with indifferent results. Third, that I was raising journalists’ salaries at The Express ‘too high’ and should desist as it would make them more materialistic and I as editor-CEO will ultimately become unacceptable “for the owner”. This, I respectfully ignored.

Editor’s Note: This article is also published in The Hindu on 25 August 2018.

As far as I remember he was the Editor of The Statesman from New Delhi.

Indeed ! Kuldeep Nayar deserved some thing better ! Nevertheless, he was a titan and would always be remembered with genuine love by his readers .