Netflix is now the most highly valued media company but market value is a function of stock price, and in this case that price is based more on investors’ hopes than concrete financials.

While you were consumed by Roseanne’s tweets and the ensuing backlash, something bigger happened in Hollywood this week. Netflix Inc. firmly established itself as the world’s most valuable media company.

Let that sink in: An 11-year-old app that charges $11 a month is worth more to investors than the legacy conglomerates that earn billions more from TV advertising, box-office hits and cable and internet packages. In fact, Netflix leapfrogged at least one traditional media giant in market value each year since 2015, when it became twice the size of Sumner Redstone’s CBS Corp. Almost symbolically, that was the same year the elderly media magnate stopped participating in CBS’s earnings calls, and spectators would soon suggest the company should buy back Viacom Inc. to reestablish its scale.

And now, Netflix—a DVD-rental-turned-online-streaming service—has unseated the final holdout, Walt Disney Co.

By the end of Thursday’s trading session, Netflix had sustained five consecutive days of more than $150 billion in market capitalization, while Disney slid to just below that level. Comcast Corp. succumbed a week earlier, and Time Warner Inc. did last year. It’s a whole new world.

Or is it?

Netflix is now the most highly valued company in the industry, but it’s hardly the biggest by any other measure. Market value is a function of stock price, and in the case of Netflix, that price is based more on investors’ hopes than concrete financials.

I’m certainly not discounting Netflix’s success or the fact that it’s unnerved the industry. But there’s a lot of talk about Netflix “beating” Disney and Comcast, when really what I think this is giving us is a clearer picture of the media landscape in a few years. These three are intent on being among the biggest, the consolidators, the names we won’t forget.

Most others will get swallowed eventually, and the next 18 months should determine who buys what. Soon, for example, Time Warner may be under the ownership of AT&T Inc., the No. 2 U.S. wireless carrier that’s been trying to morph into a media conglomerate a la Comcast, with its DirecTV satellite business and popular DirecTV Now streaming app. AT&T and Verizon Communications Inc., another potential media buyer, still dwarf Netflix with more than $190 billion in market cap each.

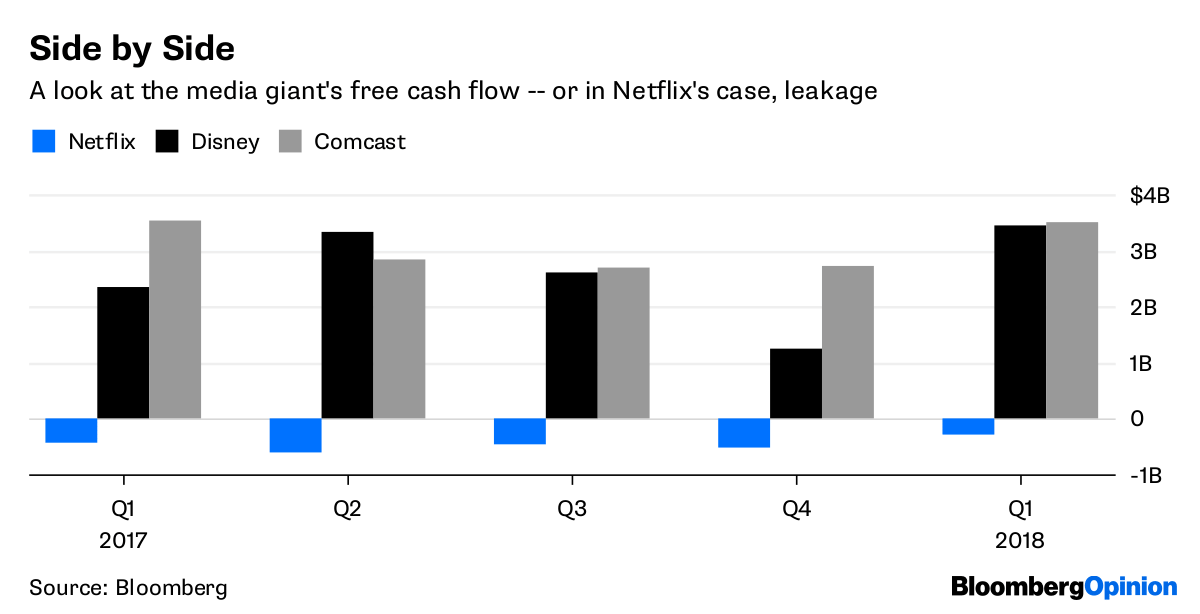

The market has punished companies like Disney and Comcast for pursuing expensive growth opportunities and rewarded Netflix for doing the same. It may someday achieve the financial success its shareholders imagine. For now, though, Netflix brings in a fraction of the revenue Disney and Comcast do, carries more debt relative to Ebitda and burns through nearly $2 billion of cash every 12 months. Disney and Comcast’s operations can generate that much cash in about a month.

Tech columnist Shira Ovide recently contrasted the money Netflix is obligated to pay in coming years for programming, leases and debt with its lack of cash generation, and it’s astonishing. And yet, Netflix is valued at more than 60 times this year’s projected Ebitda.

Meanwhile, shares of Disney and Comcast have been under particular pressure the last couple of weeks because they both want to acquire the $50 billion of assets that Rupert Murdoch is carving out of 21st Century Fox Inc. It’s the riskiest M&A move Disney CEO Bob Iger has made. For Comcast, a deal would involve a boatload of debt and the potential disruption of a set of operations that have come to be pleasantly predictable for its shareholders. Comcast hasn’t made a public counterbid yet, but hinting that it will has already dinged its stock price and Disney’s. The folks at Disney are reportedly readying a backup plan to add cash to their all-stock offer in case Comcast does come out swinging.

At the root of their fight over Fox is their need to be able to take on Netflix in the long run; Fox already knows it can’t. To me, that strategy makes sense. Just like it makes sense that Comcast is looking for more content and expanding into mobile services, that AT&T wants to control content such as HBO and that Shari Redstone wanted to package CBS and Viacom again and sell them off.

It’s also true that scale is only part of the battle. I’ve said before what I think media companies are getting wrong about streaming: There are a confusing number of apps, and some programmers including Disney are increasingly looking to keep their best content in-house for their own internet offerings. That means finding the perfect set of services to subscribe to may actually cost consumers more than traditional all-in-one cable packages. So much for choice.

But right now, solving issues like these and looking at the industry overall is just so much more exciting than how much investors have decided to overinflate Netflix’s valuation on a given day. Netflix’s market cap is bigger, it’s adding subscribers, it’s offering great content. But it’s not going to be the only TV and film house left standing. This may be about as big of a threat as Netflix gets to be, and we’re seeing who has the wherewithal to adapt and who may have to capitulate to merger pressure. — Bloomberg