Most publications have uncritically accepted the position put out by a United Nations organisation that India this month has become the world’s most populous nation. Its assessed population of nearly 1,429 million is said to be fractionally more than China’s — for the first time since modern census operations began.

The World Bank repeats the UN numbers, though it claims to use multiple data sources — none of which, however, endorses the UN position that India now has the larger population.

Importantly, neither China nor India supports the claim that India’s population has overtaken China’s. India’s population projection for 2023 is 1,383 million, whereas China’s census last December put its figure at 1,412 million.

The US Census Bureau matches census numbers with figures from India’s sample registration system (which tracks things like birth and death rates), migration data, Covid mortality, and possible mis-reporting of numbers to arrive at an India population in 2023 of 1,399 million. That’s smaller than the Bureau’s 1,413-million figure for China. And Worldometer, an independent digital data company, uses an “elaboration” of UN data to give India a current population of 1,418 million, against China’s 1,455 million.

This may seem like quibbling over small differences; if India has not overtaken China on the population metric, it will do so in the next couple of years. “Same difference”, as they say. But it is worth noting that the UN has been consistently wrong in its population projections.

In 2010, it said India would overtake China by 2021, and that by 2025 India’s population would be bigger by 63 million. Wrong on 2021, and almost certain to be wrong on 2025. In 2015 it said India’s population would cross 1,700 million by 2050. That too is unlikely to happen. The short point is that UN numbers on population need to be subjected to scrutiny, not accepted as gospel, because they are likely to be off the mark.

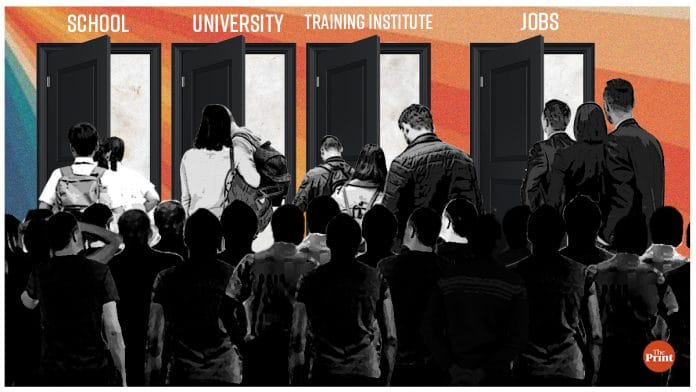

More substantively, China’s population has peaked while India’s continues to grow. Many observers have therefore pointed to the (potential) advantages accruing to India in terms of a younger population and larger cohorts in the working-age group, thereby yielding a one-time “demographic dividend”.

But this dividend has been talked about more than it has been taken advantage of over the past quarter of a century. In a country that often touts achievements ahead of their actually being achieved, the story about the demographic dividend being largely wasted is unfortunately likely to continue. China has pointedly remarked that the quality of people matters as much as quantity.

The extent of India’s population growth is itself a consequence of its failures in education and health care. Even now, an illiterate Indian woman gives birth on average to over three children, while a literate one brings down the figure to 1.9. The crude birth rate in UP is twice Kerala’s.

At the other end of the life span, the crude death rate in parts of Madhya Pradesh is eight times what it is in parts of Kerala. High death rates encourage mothers to have more children. The cycle gets broken only with education and good public health care.

The positive development is that the decadal growth rate for the country’s population has halved, from about 24 per cent in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s to under 12 per cent for the last decade — and headed lower still.

The southern and western states already have fertility rates below the replacement level. It is the poorer, less educated, less developed parts of the country whose population will keep growing for longer.

But the demographic dividend can be turned to good account only if human capabilities are built and put to productive use well before birth and death rates converge and mark the tail-end of the demographic transition, a couple of decades hence.

By then, going by current trends, India might be an upper-middle-income country approaching early middle-age. For, it will be the work of at least 20 years for India to attain the living standards typical today of parts of Southeast Asia, Latin America, or China, whose current per capita incomes (using purchasing power parity numbers) are about two and a half times India’s.

By special arrangement with Business Standard

Also read: The cost of tackling climate change & how countries’ GDP metrics may fail to accurately reflect it