In a deep dark corner of Indian YouTube, the illegal trade of pangolins is alive again. It is one of the world’s most trafficked animals and Indian law puts it in the same category of protection as tigers, lions, and rhinos. Which means there is a heavy penalty if you are caught. But in the last few weeks itself, smugglers and traffickers were arrested in Maharashtra’s Alibaug, Odisha’s Mayurbhanj, and West Bengal’s Jalpaiguri. And a YouTube comment tipoff helped Meghalaya bust a racket.

Pangolins, a scaly anteater, were in news across the world last year when they were claimed to be a carrier of the novel coronavirus. Then, China banned consumption of its meat and sale of its scales, giving the mammal high-level protection. But even the fear of Covid was not enough to steer Asia’s illegal wildlife trade off it.

In India, we found 19 active YouTube channels that uploaded 30 videos of live pangolins and 20 videos of pangolin scales, with over 18 lakh views.

Now, the pangolin is in danger both in the real and virtual world.

Also read: Coronavirus should finally make us act on illegal wildlife trade

Crime on YouTube

With an annual profit of over $7 billion, illegal wildlife trade is the fourth-largest crime industry in the world. As with any profitable business, wildlife trade is dynamic and continually evolving, and in today’s digital era of rapid networking, buyers and traffickers seem to be comfortably using social media platforms to connect with one another and fix deals. YouTube is increasingly becoming a hub for illegal wildlife trade. The endangered pangolin faces this threat of rampant online trade, certainly not helped by its emerging popularity on the video-streaming site, where it is on the verge of being openly auctioned.

A targeted scan of pangolin videos posted by Indian channels on YouTube revealed an open racket of illegal wildlife trade. Barbaric videos show captured pangolins being teased, used as props for entertainment, and even slaughtered and skinned to record the process of separating scales from the body. The criminals also performed ‘tricks’ such as the ‘electricity test’ wherein the animal is poked with a metal screwdriver connected to a bulb, which supposedly lights up, and the ‘bubbles test’ to show that the scales apparently produce bubbles when dipped in water — all made-up tactics to attract buyers and increase prices.

But over 18 lakh views on the videos show the scale of the market. The videos have flourished between 2011 and 2021, especially from 2018.

Also read: China is drawing all the flak, but is India controlling its wet markets?

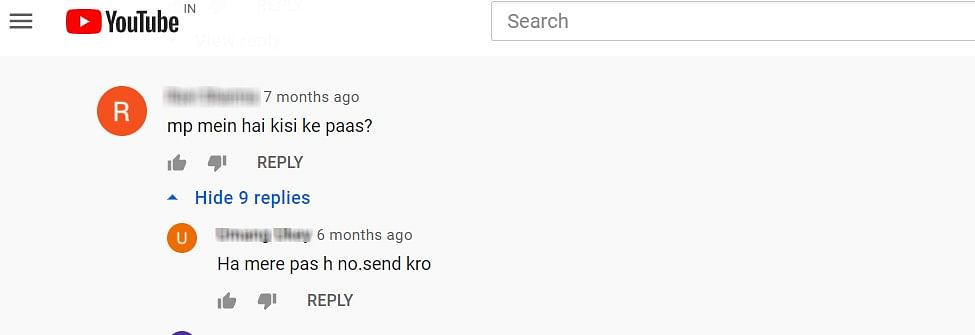

And the YouTube comment section plays a big role in it — it is now the hunting ground for buyers, traders and middlemen. The modus operandi is to seek buyers/sellers by stating availability or interest in wildlife articles, exchange contact numbers, and then continue chatting in private to fix deals.

We calculated that about 24 per cent of a total of 1,682 comments posted on the videos were directly related to illegal pangolin trade, and all communication threads are active to date. These comments laying out in the open reflected complete disregard for the animal’s well-being, no fear of the law, and were bone-chilling. Take a look at these:

“Hello, I want to buy the bone that is extracted from a female pangolin after birth. If you have this twisted bone, send me a message on WhatsApp, this number is XXXXXX.”

“Pura jinda hai bhai kisi ko chahiye to address Balrampur, Chhattisgarh [It’s completely alive; if someone wants it, the address is Balrampur, Chhattisgarh]”

“I want to buy a Pangolin, is there any way to import it to Europe?”

A total of 183 individuals had posted their contact numbers in the 50 videos we saw, of whom 114 were identified as buyers and 69 others looking to sell live/dead pangolin and its body parts. Majority of these individuals hailed from forested states of Chhattisgarh, Telangana, Odisha, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and the northeast. Surprisingly, the state of Bihar was found to host the maximum buyers and sellers trading in pangolin scales. Additionally, seven international contacts (3 buyers and 4 sellers) were recorded from Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Iraq, Czech Republic, and Indonesia.

The users also did not bother being careful with code words, which may hint at a lack of fear of national/international law. It was shocking to find traders dealing even on an Indian news channel’s video about a pangolin seized by enforcement authorities!

Another disconcerting realization is the rising trend in the number of videos in recent years with an explosion of trade-related queries. While the earliest video appears to be operational since 2011, the past three years have seen an increase to 10 videos in 2018, 15 videos in 2019, 9 videos in 2020, and as many as 12 videos till May this year. The increased activity in the comments section is attributed to both the growing awareness about illegal pangolin trade as well as an increase in online networking among traders and middlemen.

Rare animals such as turtles, sand boas, tokay geckos, and a variety of wildlife articles are also being traded online.

Also read: How a tiger is poached in India in 2019: Breaking down the supply chain

No protective shield

When a blanket ban on the international trade of eight pangolin species came into effect in 2016, a glimmer of hope arose for the mammal. The pangolin is the only scaled mammal, which is also the cause for its unfortunate status of being one of the most exploited and traded.

The scaly shield that evolved over millions of years to function as a defence mechanism against sharp-toothed predators is rendered useless against human poachers. The slow and shy mammal is simply caught and bagged for consumption or traded among several communities worldwide for its myriad unproven medicinal properties. Ironically enough, the pangolin’s ‘protective’ shield is driving the species to extinction.

Although protected under Schedule I of Wildlife (Protection) Act 1972, Indian and Chinese pangolins are poached and traded widely across India for meat and scales. The scenario seems to be changing from opportunistic hunting for local subsistence to intentional capture and slaughter for the purpose of commercial trade. In spite of a relentless government-led crackdown, the market demand and continued functioning of crime networks pose a grave threat to the rare species, the population of which is unknown in India.

An urgent requirement would be to choke the ease of communication among prospective buyers and traders as well as call out the perpetrators using a dedicated wing of the cyber-crime division and wildlife law enforcement authorities. Media attention regarding the peril of pangolins seems to have helped spread awareness about the issue, and the involvement of common citizens in reporting instances of online trading and thereby assisting law enforcement agencies could be beneficial in curtailing its irreversible expansion. Content posted on YouTube is loosely regulated despite the provision of policies outlining expectations and limitations, wherein the site heavily relies on consumers to report (‘flag’) policy violations or illegal content. In the case of animal abuse, reporting under the “violent or graphic content policies” guideline is heavily reliant on an individual’s ability to detect signs of distress or mistreatment, which may vary significantly.

Media platforms like YouTube must take greater responsibility in regulating content and promote robust software to detect keywords related to species names, use of trade-related words, and flag them immediately. The flagging could potentially inform viewers with warnings about illegal trade and killing of endangered species, and remove entire videos or channels that promote such trade.

India has to protect its pangolins.

Monesh Singh Tomar works to combat illegal wildlife trade across the country. Abhipsha Ghosh is a conservationist working in the field of human-wildlife conflict. Kunal Sharma is a conservationist focussing on indigenous people in the southern and central forested landscapes. Views are personal.

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)