In his column published in ThePrint – “Why well-to-do Indians are fleeing the country and economists aren’t returning” – journalist T.N. Ninan argues that despite considerable economic progress, India is no longer an attractive place to live and work for those with opportunities abroad. He cites the trend of businesspersons and other wealthy people opting for “overseas citizens” status to support his argument. There may be some truth in this.

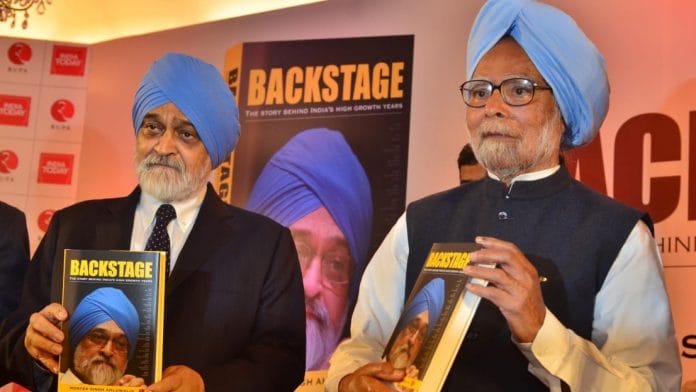

However, to say that influential policy economists like Manmohan Singh, Montek Singh Ahluwalia (whose book release prompted the subject of the editorial), Rakesh Mohan, Vijay Kelkar do not immediately return to live and work in India is quite a different matter. The fact is that the trend of businesspersons exiting India is recent, but the absence of talented economists like Manmohan/Montek et al has been with India much longer.

The engagement with the government – in terms of tenure, point of entry and exit – of economists like Arvind Panagariya, Raghuram Rajan, and Arvind Subramanian are qualitatively different from those of earlier generation sarkari economists. Arguably, the species of the laterally inducted sarkari economist is now extinct because all the eminences have retired without a pipeline of succession.

Also read: Why well-to-do Indians are fleeing the country and economists aren’t returning

Stakes are different

In the 1970s, 1980s and early/mid-1990s, the point of lateral entry for economists in government was as economic adviser, a joint secretary-level position in major economic ministries whether it’s finance, commerce, industry, steel, or the erstwhile Planning Commission. These positions were advertised and selected by the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) and were open for “outsiders”. To attract talented economists, age and experience requirements were considerably lower than what would be required for a career bureaucrat to be promoted to the joint secretary level.

The reason Manmohan Singh and Montek et al returned to India wasn’t because India was an easy place to live and work (salaries were low and government housing sub-par). It is because they had an opportunity to work in, and work their way up, in India’s economic policy system at a very young age (most of them came in their 30s or early 40s). Note that none of them were marquee names when they came. The fame was acquired in India (unlike Panagariya, Rajan and Subramanian who made their names overseas).

This career path was effectively closed for economists of potential during the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government in the late 1990s, when almost all of the economic adviser posts were “encadred” for career Indian Economic Service (IES) officers. It is a pity that no government, particularly the two led by Manmohan Singh, could reverse this. From then on, the points of lateral entry for economists were few and at the very top: principal economic adviser post in the Ministry of Finance (additional secretary-level), chief economic adviser, deputy governor of the RBI (secretary-level positions) or governor of the RBI (minister of state-level), and vice-chairperson of Planning Commission/NITI Aayog (cabinet minister-level).

In order to get any of these positions directly, one had to be an economist of great eminence, which Panagariya, Rajan, Subramanian and even Kaushik Basu (in the UPA) were. But because of their eminence, they also had plenty of exit options as well as a career on pause in the West. When Manmohan Singh, Montek and others returned, they weren’t star academics and were holding mid-level positions in international organisations. The stakes are entirely different.

Also read: Modi govt must learn — instinctive response not always best solution to economic problems

Early entry, security of tenure

Unsurprisingly, the earlier generation of lateral entrants had a much greater influence than the recent stars. For one, because they came in at the joint secretary-level in their 30s, they had much longer tenures. They were absorbed as career civil servants and rose gradually to additional secretary and secretary-level positions in a clear career path. Their tenures were secured. Most importantly, they acquired the experience and skill of navigating the government machinery by spending time at the cutting edge of government: the joint secretary-level.

At least one reason that the later economists, who were parachuted straight to the top, suffered in being as effective as the earlier generation economists was their lack of familiarity with the way the complex beast of the government of India functions. The inexperience also made it harder to co-habit with career bureaucrats, a quality critical for achieving any outcome. The recent unhappy or unsuccessful or short-lived experience of the star economists at the top will only dissuade other economists from making the leap straight to the top.

I would wager that plenty of young Indian economists abroad would still opt to return to work in the government if they are given opportunities at an appropriate level and provided a career path. In fact, the government should consider whether it wants a sizeable Indian Economic Service at all when plenty of professional economists can be easily hired from the marketplace. There can be no argument with the need for a pool of top-class economists who can serve an increasingly complex and large economy over the next two or three decades.

The author is Chief Economist, Vedanta. Views are personal.

Bharat doesn’t want economists. It wants only Kejriwals and their freebies. jai karl marxa. Jai communist raja.