The recent row over ‘I Love Mohammad’ made me think of my own upbringing in the Barelvi Muslim community. Barawafat, also known as Mawlid, Milad-un-Nabi, or simply the Prophet’s birthday, was a season of warmth. Neighbourhoods came alive in ways that stay with you. Streets would glow with strings of lights, temporary arches were built with great care, and beautiful displays were set up to mark the occasion. Men and women would gather for processions and night-long prayers.

Then there were the relics—sacred objects carrying the weight of both history and faith—put on display for all to see, filling people with reverence and respect. For a child, it felt magical, as if faith was not only something private but something shared, lived, and visible. Looking back, it wasn’t just about ritual; it was about belonging, about a community affirming its place through celebration.

The only controversy I had ever known around Barawafat was theological. Ultra-conservative movements like Wahhabism and Salafism long dismissed the commemoration as an “undesirable innovation” (bid’ah), claiming it had no roots in the Quran or the early practice of Islam. For that reason, the celebration is outright forbidden in places like Saudi Arabia and Qatar. But even then, the conflict felt distant—something happening far away, in societies shaped by their own rigid interpretations.

Devotion is now provocation

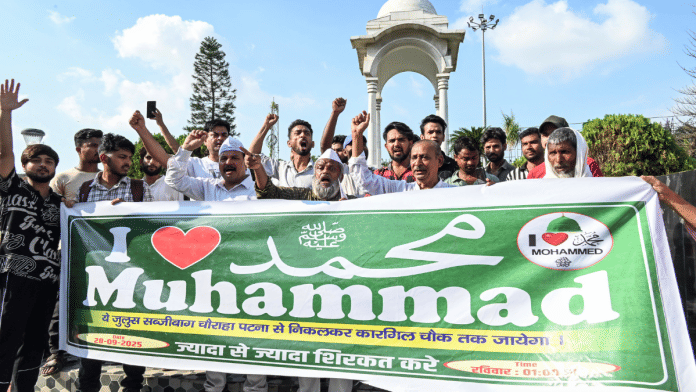

Here in India, especially within the Barelvi community, Barawafat was not debated; it was lived. It was joy, remembrance, devotion. I never imagined that this day itself would become the centre of controversy, not because of theological debates, but because of a simple message of devotion. That a banner displaying just a few words, “I love Prophet (PBUH),” could stir suspicion, arguments, and even political noise speaks volumes about how deep the distrust is between communities. An expression of faith and love has now, somehow, become a matter of contention and politics.

The counterargument being pushed is that this is not just about the “I Love Muhammad (PBUH)” poster. They say an FIR had to be lodged because such a display had never occurred before, that it was a “new tradition” introduced by the organisers of Barawafat, and that putting it in a new location could potentially spark chaos. But how does a simple message of love for a religious figure become a provocation? Even if it is a new addition, even if it is displayed in a different place, what does it say about us if our response is suspicion rather than acceptance?

It almost mirrors the flawed reasoning often used when Hindu religious processions pass through areas considered “Muslim localities,” and any objection or violence is excused as if it were inevitable. That logic is as absurd then as it is now—because at its heart, it assumes people cannot coexist, cannot tolerate another’s religion without seeing it as somehow “anti” their own. And once that thinking takes root, it feeds into a cycle of mistrust: one side feels threatened by the other’s expression, the other side grows defensive and suspicious in return, and soon enough, even the smallest gesture—whether a procession, a poster, or a prayer—becomes loaded with tension. Devotion and celebration are now rebranded as provocations, and communities in India are growing apart.

And that’s what needs solving on the ground—because the politics around such incidents do nothing for ordinary citizens. They only serve politicians. The loudest voices, claiming to speak on behalf of entire communities, gain power without ever delivering real governance, without ever being accountable. And what do ordinary people get in return? At best, a hollow sense of security or a shallow feeling of supremacy over another community.

Also read: Muslims at garba—whenever a festival becomes exclusionary, we lose a piece of India

It started with us

Let’s not pretend this divide is built entirely by others. As a community, Muslims too have contributed enough to deepen it. When chants like “Sar tan se juda”—a call for murder in the name of blasphemy—become normalised in protests, we added fuel to the fire. As Maulana Wahiduddin Khan always said, the Quran prescribes no punishment for blasphemy—you counter an argument with an argument, not with a sword. But we failed to embrace civil disagreement. We justified conditional violence. We politicised our faith. And today, even a simple and affirmative message of love is read as an attack. This doesn’t absolve those who thrive on hatred and unfairness, but it does mean we, too, have some soul-searching to do.

If we want to reclaim our festivals, our faith, and even our public spaces, then we must begin by refusing to let love be weaponised. But that can only happen when communities stop turning every difference into a battlefield, and when we learn to separate faith from the politics of power. Because once devotion becomes a competition, everyone loses—the meaning of religion, the spirit of coexistence, and the ordinary people who only want to live without fear.

Amana Begam Ansari is a columnist, writer, and TV news panellist. She runs a weekly YouTube show called ‘India This Week by Amana and Khalid’. She tweets @Amana_Ansari. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

A sane voice. Afaik, Hindus are by nature secular and can and do tolerate and respect other religions. But having been provoked since long by their own and others, this extremist streak has crept into them which is inevitable. This is not desirable, and not the character of the religion.

Author’s intensio intension is good. But she should remember how much a call ” Jai Shriram” created uproar? Remember the position taken by Mamata didi and her followers ? And everybody knows how Islam and politics are intertwined!