India’s trade policy has become increasingly outward-oriented in recent years.

The trade agreement with the United Kingdom was finalised in 2025, and the pact with the European Free Trade Association is already operational. The long-negotiated agreement with the European Union has now been signed and is poised to come into effect shortly. In these deals, tariff cuts and reduced non-tariff barriers are used deliberately to improve export competitiveness and integrate domestic producers into global markets.

Even the earlier Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement with Australia indicated a readiness to significantly reduce tariffs. The message is evident: India seeks export-driven growth and deeper integration into global value chains. However, a more challenging question is rarely addressed.

When India reduces tariffs under trade agreements, does liberalisation genuinely reach the market?

A recent working paper by Abhishek Anand and Naveen Joseph Thomas on viscose staple fibre (VSF) prompted me to consider this issue more seriously. Their study illustrates how tariff reductions under the ASEAN-India Trade in Goods Agreement (AITIGA) were formally implemented but were repeatedly offset by policy measures. While the tariff barrier was lowered, effective protection remained unchanged.

The rotation of protection

Viscose Staple Fibre (VSF) is a crucial raw material in modern apparel production. Under AITIGA, India pledged to abolish tariffs on imports from Indonesia. However, coinciding with the scheduled reductions, anti-dumping duties were imposed in 2010 and subsequently extended. In 2018, Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariffs were increased. Following the withdrawal of these duties in 2021, a Quality Control Order was implemented in 2023. While the tools changed—tariffs, trade remedies, and regulations—the outcome remained the same: continued protection for foreign competition.

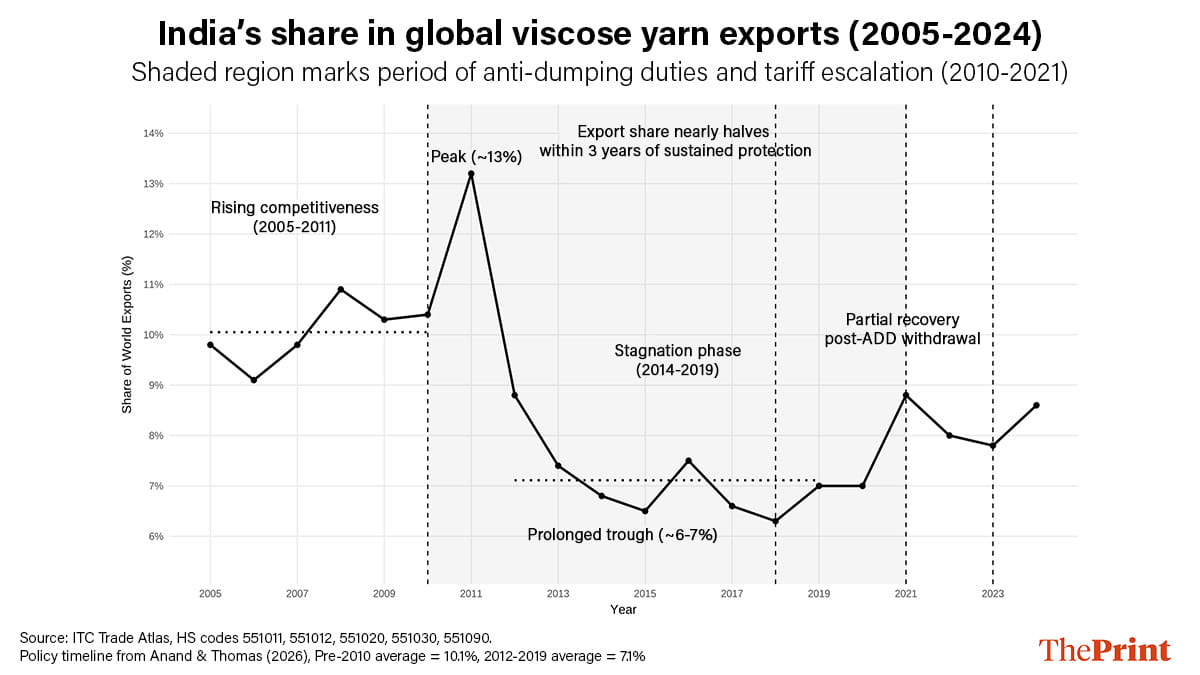

During this period, the domestic market was predominantly controlled by a single producer, which accounted for 94 per cent of consumption at the time of investigation. By comparing domestic prices with international benchmarks, the study estimates that this protection resulted in excess gains of $2.5 to $3.1 billion between 2010 and 2024. Protectionism under a monopoly does not foster competitiveness; rather, it reinforces pricing power. The downstream effects were significant. Following the imposition of anti-dumping duties, India’s share in global viscose yarn exports experienced a sharp decline and remained low for over a decade.

The timing is indicative. The decline coincides with periods of input insulation. Upstream protection functioned as an implicit tax on labour-intensive exporters.

Also read: RBI is buying time by not cutting the repo rate. Past policy needs a breather to work

A structural trap in ASEAN

However, the narrative surrounding fibre is merely one aspect of the broader picture.

In a separate research article concerning trade between India and Indonesia, I analysed the structural composition of India’s exports utilising product complexity measures.

The findings were quite revealing.

Indonesia’s GDP significantly influences India’s exports, with an elasticity of approximately 1.28, thereby affirming that trade is predominantly demand-driven. However, the nature of the exports is quite concerning. The weighted average Product Complexity Index of India’s exports to Indonesia is negative (approx -0.12).

More concerning is the strong negative correlation (approx -0.42) between export shares and product complexity. Simply put, India exports a greater volume of low-complexity products and a lesser volume of high-complexity ones. The export portfolio is dominated by petroleum products, basic chemicals and iron, while pharmaceuticals and advanced engineering goods are notably underrepresented.

This indicates that even with tariff reductions, the trade structure does not automatically upgrade.

Applied to the fibre sector, protecting man-made fibre producers and allowing prices to remain above global levels hurts downstream exporters, making them less competitive internationally. This, in turn, locks India into a commodity-heavy export profile in ASEAN markets. The outcome is a self-reinforcing cycle: upstream protection, diminished downstream competitiveness, and a persistent inclination toward low-value exports.

This issue extends beyond a single fibre. A similar pattern is evident in polyester staple fibre, where anti-dumping duties and tariff adjustments have also shielded upstream producers. Across man-made fibres, the pattern remains consistent: upstream protection and downstream challenges.

It is high time we recognised that free trade agreements are not merely about reducing tariffs; they are instrumental in facilitating structural transformation. If tariff reductions are consistently counteracted by trade remedies or regulatory barriers, and if domestic policies persist in elevating input costs, then trade agreements risk becoming performative rather than transformative.

India’s objectives are clear: to integrate into global value chains, expand labour-intensive manufacturing, and enhance engagement with ASEAN under the Act East policy. However, these aims are difficult to achieve while simultaneously protecting a small group of upstream producers and expecting downstream exporters to remain globally competitive.

While tariffs can be reduced through notification, achieving competitiveness necessitates coherence. The true measure of India’s new trade agreements will not be the quantity signed, but whether domestic policy ceases to cancel their effects and whether the export portfolio transitions from petroleum and basic chemicals to pharmaceuticals, engineering goods, and complex manufacturing.

Until such a shift occurs, liberalisation may remain visible in official records but absent in the empirical data.

Bidisha Bhattacharya is an Associate Fellow, Chintan Research Foundation. She tweets @Bidishabh. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

All these protections must go. Otherwise, we will never learn.

I think India fosters a deep mistrust of foreign capital. We experienced centuries of foreign rule, because the rulers allowed foreigners to own businesses in their territory.

This cultural learning pushes us to make entry into India difficult and exit nigh impossible. The case of general motors journey reflects this.