Preconceived notions that women will confine themselves to domestic caregiving to uphold the social standard and let their unpaid work act as a social and financial safety net keep many women from entering the labour market. Even those who do manage to move out of the domestic sphere often find that only a few options are accessible to them. This trend persists despite India having supporting policies to encourage women to enter the labour market.

The Maternity Benefit Act (MBA) was amended in 2017, making it mandatory for companies with more than 50 employees to offer a creche on the premises, with costs to be borne by the employee. The amendment was supposed to encourage more women to join the workforce without sacrificing their responsibility of providing their children with the necessary care. Sadly, seven years later, we are still in the dark about how many companies comply with the rules.

Since women are typically expected to be the primary caregivers in a family, they shoulder a disproportionately greater share of household duties and childcare responsibilities than men. Compared to men, women are less likely to receive assistance with household duties and childcare. Based on the National Sample Survey Office’s (NSSO) Time-Use Survey Report 2019, a man spent an average of 74 minutes a day on childcare whereas a woman spent 134 minutes a day.

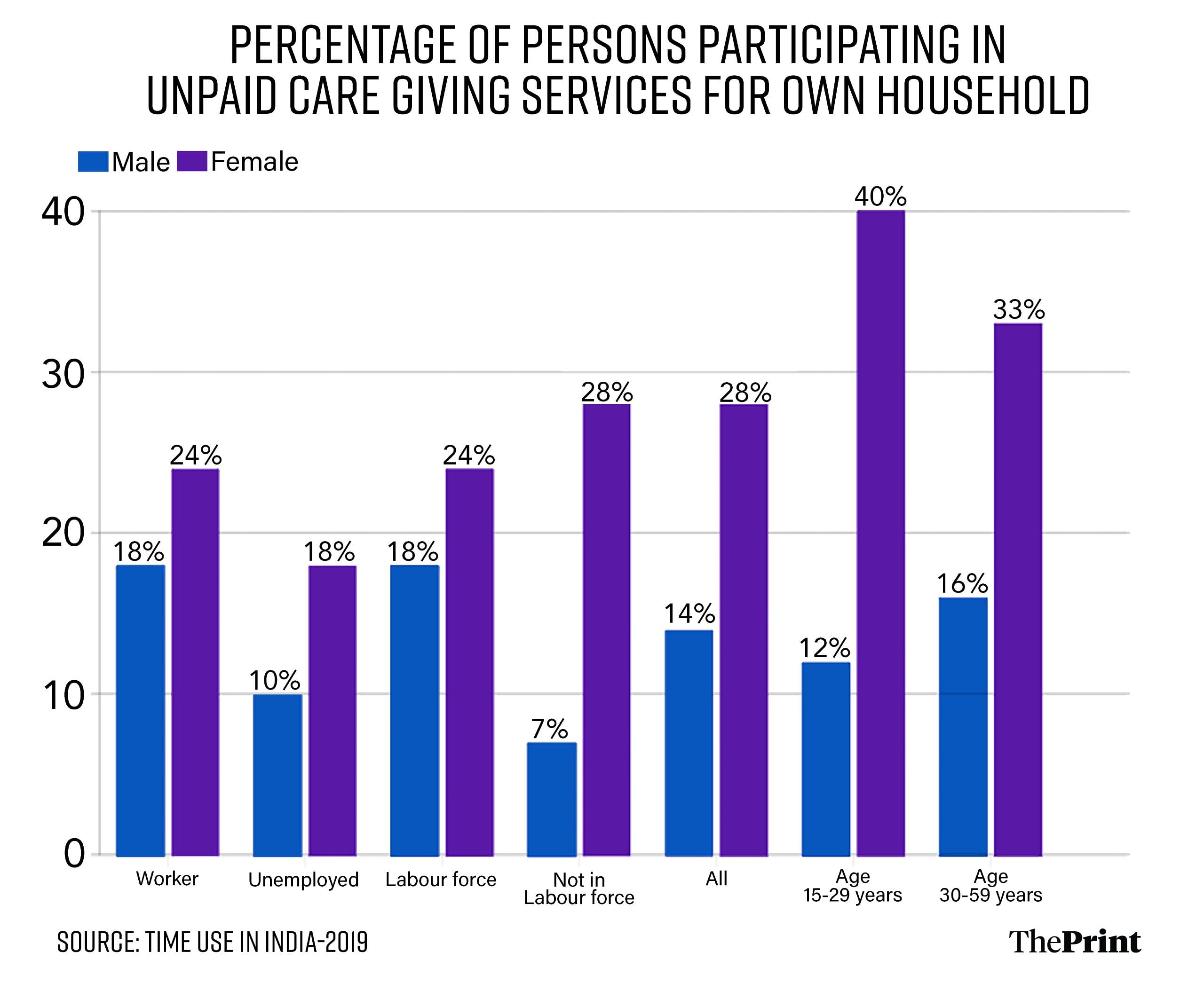

Furthermore, care given to other family members is so gender-defined that irrespective of any other paid activity, women spend a definite length of time in unpaid activities, specifically caregiving activities. About 40 per cent of women between 15 and 29 years of age are involved in caregiving activities as against only 12 per cent of men of the same age group. Among those outside the workforce — women neither looking for a job nor currently working — about 29 per cent do unpaid care activities as against only 7 per cent of men. This indicates how unpaid caregiving services have impacted the employability of women. Household responsibilities keep women outside the workforce, and the case is completely contradictory for unemployed men.

This data, though, does not prove that women’s engagement in unpaid caregiving work is the most likely contributor to their lower participation in the workforce.

It is undeniable that having a young child substantially decreases women’s autonomy over their own time. At the same time, it has a normatively less effect on men’s activities and time. This caregiving has been even costlier, both physically and emotionally, when it comes to daily wage earners, which adds an additional worry of having an unattended young child.

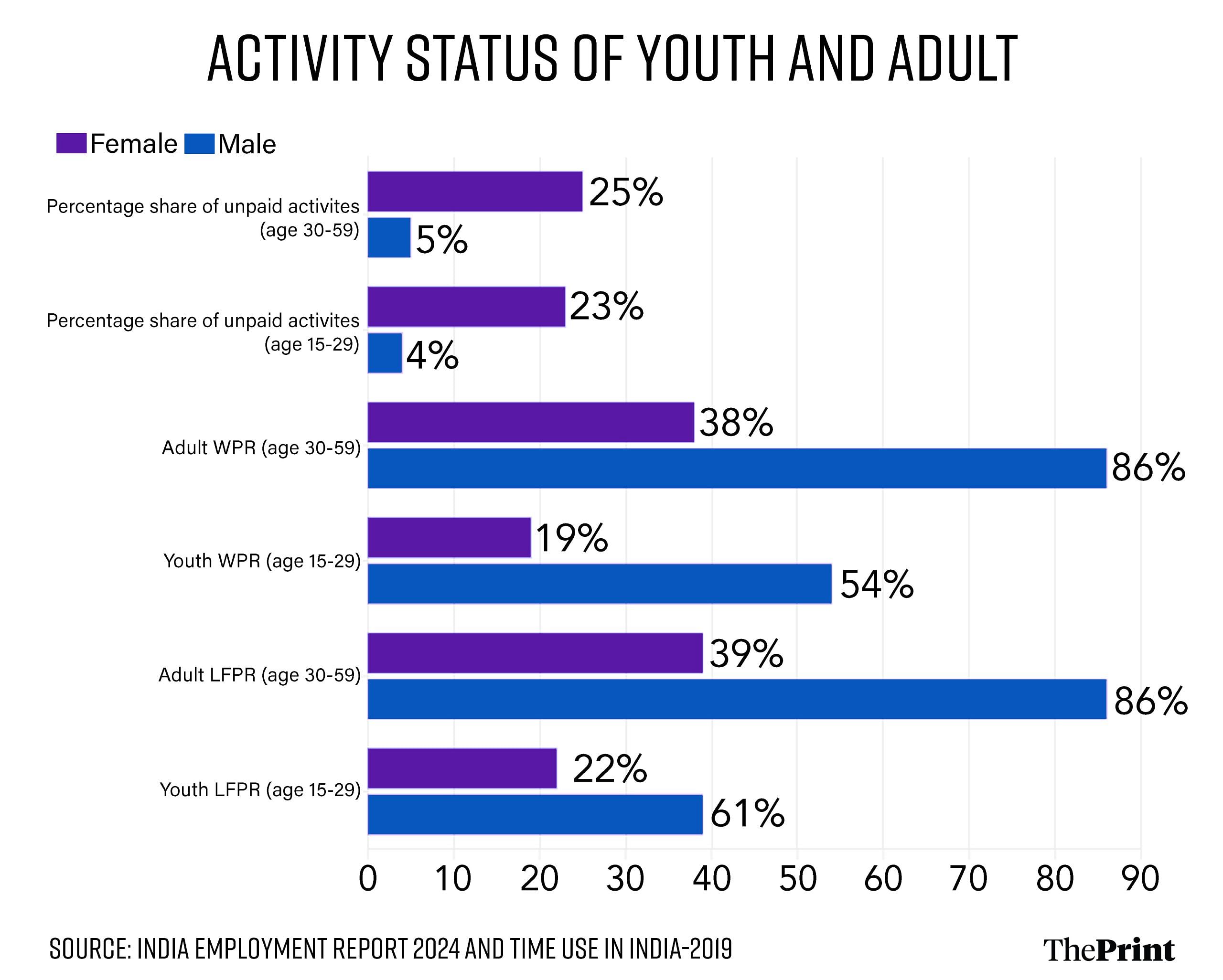

“Demographic dividend”, which is expected to boost economic productivity, occurs when there are more working people than dependents. While India should potentially soon reap the benefits of its demographic dividend, a recent study titled The Other Half of the Demographic Dividend by Sonalde Desai suggests that the actual rate would likely be significantly less than anticipated. She observes that the dependency ratio of the non-working-age population to the working-age population is more than double if the differences in worker population ratio are considered. Women constitute half of the country’s population. The India Employment Report 2024 also highlights the likelihood of young women (in the age group of 15 to 29) not being in employment, education, or training is higher at 48 per cent, which is almost five times that of men (at 10 per cent) in 2022. Also, a young woman spent six times more than the young man in unpaid activities as a share of the time spent in all activities.

The share of young men (15-29 age group) involved in economic activity (Worker Population Ratio or WPR) was 54 per cent, while that of young women of the same age group was only about 19 per cent. Thirty-two per cent of non-student young women who are in the workforce as against 97 per cent of non-student young men, according to the India Employment Report 2024. Consequently, the Worker Population Ratio (WPR) and Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) of males are approximately three times greater than those of women in the 15–29 age bracket, and over twice as great in the 30-59 age bracket.

Learn from these states

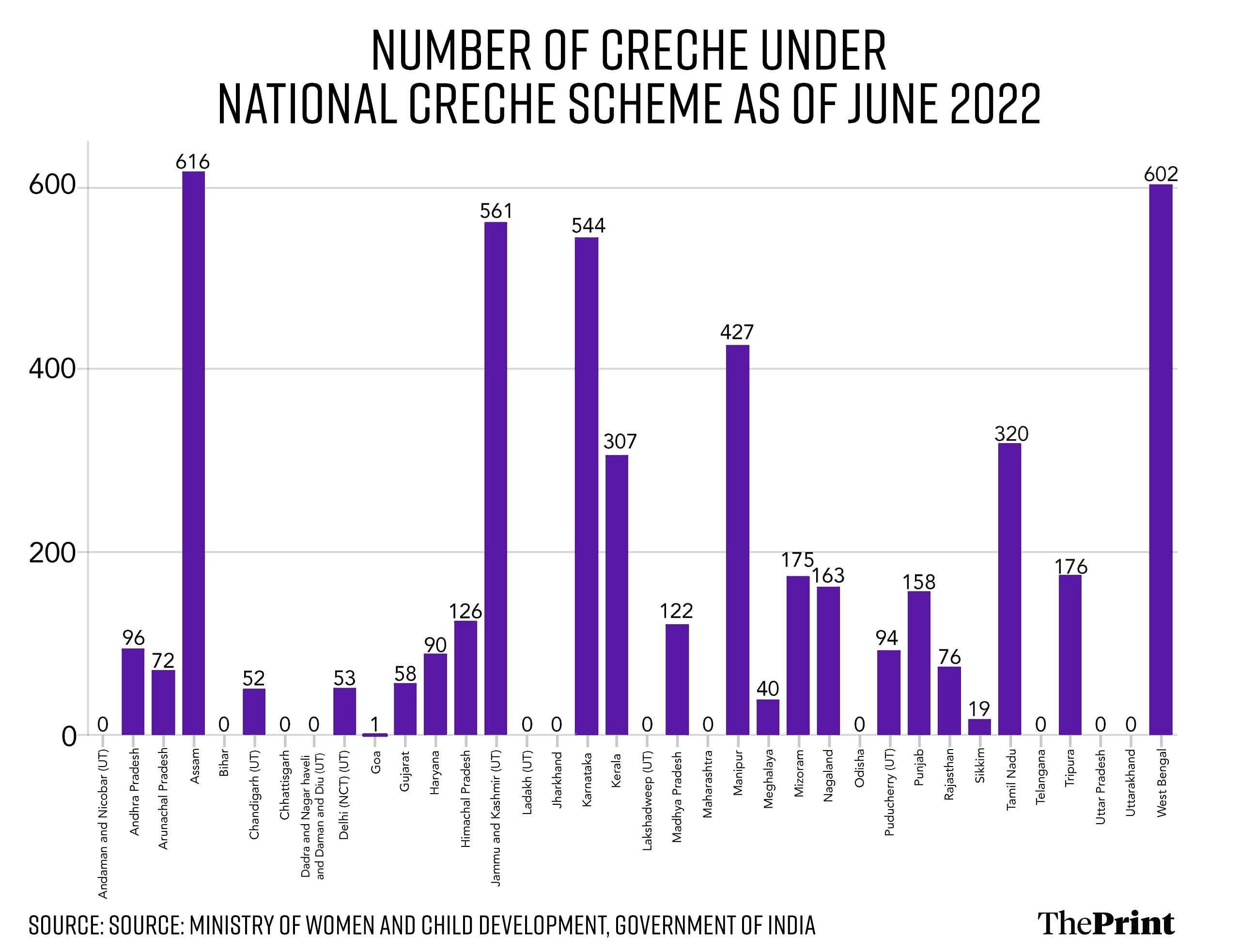

Tackling gender inequality in the workforce may result in a notable increase in economic output as well as the empowerment of women economically. Providing childcare might enhance their agency, aid in their pursuit of greater economic parity, and, as a result, greatly boost the economy. The National Crèches Scheme and the Palna Scheme under the Mission Shakti Project of the Ministry of Women and Child Development gave state governments the option to establish standalone crèches or convert Anganwadi centres into crèches in addition to the MBA. The Assam, Karnataka, Odisha, and Haryana state governments have begun to take action. The central government wrote to the states in November 2017 — four months after the deadline of MBA — requesting them to frame and notify rules for companies to set up the creche facility. Yet, only Karnataka had notified the maternity benefit rules as of May 2020. Tamil Nadu announced the regulations in January 2021, followed by Haryana in July 2023. The Shops and Establishments Act of Maharashtra has the clause. The following chart highlights the number of creches under the National Creche Scheme and also displays the states notified in the MBA. Central data maintenance is not available for the crèches operated by private NGOs and those covered by the MBA.

Childcare is neither a market commodity nor a social programme but a right of women. Empirical evidence proves a direct correlation between access to childcare and women’s labour force participation. The expansion in the caregivingeconomy not only gives greater opportunities to mothers but also creates formalised jobs for women to be engaged in the care economy. Apart from the crèche facilities, day-boarding is also an underexplored option as a solution. The model is prevalent only in big cities and is still at a nascent stage. It can actually provide a better panacea for all-round child development and, at the same time, build a holistic childcare ecosystem, which can support a working environment for women.

We have the national minimum standards and protocols for crèche facilities, as well as acts and amendments that establish the requirements of the childcare infrastructure. But the implementation of this requires some initiatives at the local level too. Some states have already taken up initiatives in this direction, which can be followed to create a well-thought-out strategy and a fiscal plan for implementing them in other states.

Nijara Deka is Associate Fellow, National Council of Applied Economic Research. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)