Canada, which took over the G7 presidency from Japan in December 2024, has finally invited India to the upcoming G7 summit, evidently belated wisdom. Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the invitation on X Friday evening, following a communication from his Canadian counterpart, Mark Carney. The two leaders are expected to meet on the sidelines of the G7 summit in Kananaskis later this month.

This is not the first flip-flop, as the former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, after accusing New Delhi of alleged hand in assassinations in Canada, admitted that “No evidentiary proof” was given to India. His flip-flop on the Hamas-Israel conflict is no secret.

At a time when the world’s economic center of gravity is shifting towards Asia, and India has demonstrated leadership on multiple global platforms — including its recent G20 presidency — the delayed invitation suggests that Canada is unbothered by the detractors who continue to portray bilateral ties as “deteriorating,” though, without offering a clear explanation to silence the critics. As a mature statesman and a suave diplomat, PM Modi has accepted the invitation.

Canada seems to be missing a golden opportunity to reset bilateral ties and begin a new chapter of peace and development. This flip-flop is somewhat unfortunate and does not bode well for the G7’s own ambitions — whether it is addressing climate change and global inequality or fostering cooperation with emerging economies, agendas it has pursued over the past three decades.

From Castle Rambouillet to a crisis of relevance

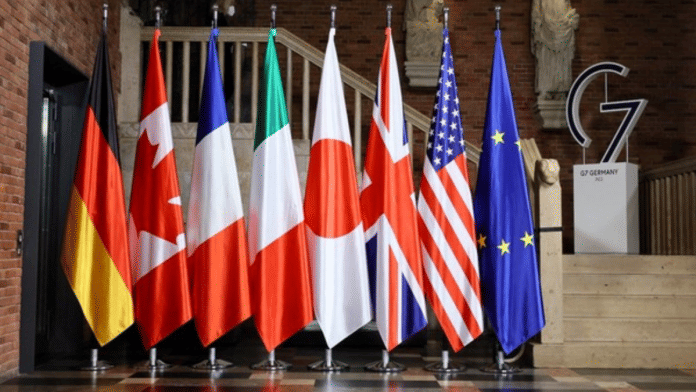

It’s worth remembering how the G7 began. A ‘fireside chat’-turned-‘Library Group’ started by US treasury secretary George Shultz in 1970 to address currency turbulence bloomed into G6 five years later. On 15 November 1975, about five months after Indira Gandhi had imposed Emergency in India, leaders of six democracies — the US, UK, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan — met at the Castle of Rambouillet near Paris.

Today, none of the leaders from the “Summit of the Six” — James Callaghan (UK foreign secretary), Henry Kissinger (US secretary of state), Gerald Ford (US president), Takeo Miki (Japan prime minister), Helmut Schmidt (German chancellor), Jean Sauvagnargues (French foreign minister), Valery Giscard d’Estaing (French president), and Mariano Rumor (Italian foreign minister) — are alive, and most of the countries no longer dominate the global economy.

The G6 became the G7 in 1976 with Canada’s inclusion, and the G8 between 1997 and 2013 with Russia onboard— until Russia’s suspension after the Crimea annexation in 2014.

Collectively, the group expressed concern about their respective economies, donned the mantle of the “white man’s burden” to discharge their responsibilities toward the ‘Third World’, and decided to meet again. Fifty years later, none of the world’s problems have been solved by these countries, and except for the US, the rest are no better off than the countries of the “poor South.”

Also read: India is walking a geopolitical tightrope. It can shape New Delhi’s diplomatic power

G7’s expanding mandate, shrinking impact

Over the years, G7 summits have taken on a broad agenda: gender equality, global health, climate change, and sustainable development. In 2021, the UK-led summit committed itself to a “green revolution” and net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Germany’s 2022 presidency established a “Climate Club” to implement the Paris Agreement, and the 2023 Hiroshima summit reaffirmed commitment to phasing out fossil fuels.

India participated in all these meetings, contributing immensely to the resolution and their implementation. Ironically, it was Donald Trump-led “G1 within G7” that derailed consensus, dismissing global warming as a “hoax.” Now, with Trump 2.0 back in the mix and India 3.0 out, can the G7’s green agenda survive?

Patronising rhetoric, no real support

The G7’s agenda of connecting with emerging economies and adopting an inclusive approach has often rung hollow. Italy included an “African Segment” in the 2001 summit, but without serious financial commitments and steps to resolve issues of poverty and migration. African leaders left disappointed, questioning the G7’s sincerity. In contrast, India, during its G20 presidency, successfully pushed for the African Union—representing 55 African countries—to become a permanent G20 member.

Who, then, is more relevant and committed to inclusive global development: the G7 or the G20?

The 2021 G7 summit in London also introduced the Global Minimum Tax (15 per cent), aiming to rewrite international tax rules and discourage multinational corporations from taking undue advantage of lower taxes in smaller or developing economies. This again faced serious objections, with critics arguing that the G7 had no democratic legitimacy to act as the captain of the global economy.

India: From Bandung to BRICS

India’s global economic role didn’t begin yesterday. New Delhi has emerged as the fulcrum of Asian economic development since hosting the 1947 Asian Relations Conference and leading the Bandung Conference in 1955, where the foundation of the Non-Aligned Movement was laid. Now, it has positioned itself at the centre of South-South Cooperation.

The successful Indian presidency of the G20 followed by its developmental agenda with IBSA (India-Brazil-South Africa) are proof of India’s unique leadership position in the geo-economic dynamics of Asia and South Asia. It has also championed inclusive global governance in a way that the G7 often only gestures toward.

Time to re-evaluate the relevance of G7

The economic, political, and cultural divides of the 1950s and 1960s are out of syllabus, phased out of academic discourse due to globalisation and rapid rise of ‘Southern’ economies. Between the 19th and the 21st century, there was a total metamorphosis that has left several centuries-old theories, perceptions and ideas redundant.

The old binaries of the Cold War — East vs West, North vs South — have blurred into insignificance in the face of a new and emerging global economic order, necessitating a new approach to the contemporary history of global economic development.

The G7, once seen as the anchor of global economic stability, is no more than a relic of the past today. India would do well to invest its diplomatic energy elsewhere: G20, BRICS, IBSA, and regional platforms that better reflect the world as it is, not as it was. Let the G7 gently go into oblivion — and take the outdated and irrelevant worldview it represents with it.

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated to include Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s announcement on X regarding the invitation.

Seshadri Chari is the former editor of ‘Organiser’. He tweets @seshadrichari. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)

The United States, or more accurately the Trump administration, is ambivalent towards G 20. May skip this year’s summit. Part of a larger aversion to international organisations like the UN. Actively opposed to BRICS. Its potential as an enlarged body to create an alternate pole of global influence. Contributing to a decline in USD’s status as a global reserve currency. So India will have to navigate these shoals carefully.