In the Karnataka-Hyderabad region, it is the AHINDA (Dalits, backward classes and minorities) versus the Lingayats. And the mining Reddys could just tilt scales in BJP’s favour.

The Kannada-speaking districts of the Nizam’s kingdom that were merged with Karnataka in 1956 are the most backward parts of the state. It is an arid zone, but blessed with rich mineral reserves. With 40 seats in the assembly, it was a Congress stronghold, before the Janata Dal emerged since the 1994 elections. The BJP has gained strength here since 2004.

In 2013, the UPA government secured recognition for the region under the Article 371 (J). This led to the creation of a Hyderabad-Karnataka Region Development Board, with Rs 2,500 crore allocated. Seventy per cent seats in medical, dental and engineering colleges located here are reserved for local students, as 75-85 per cent of the jobs. Eight per cent educational seats are reserved for students from the region in the rest of the state.

This came in the run-up to the previous assembly elections, and the Congress reaped the benefits, winning 23 seats, as against 14 in 2008.

With the three-way split in the BJP, with the breakaway factions of B.S. Yeddyurappa and B. Sriramulu, the party won a mere five seats, as against 21 in 2008. The JD(S), a non-player here, made surprise gains in traditional bastions of the Congress and BJP, winning five seats. Sriramulu’s BSR Congress won two seats, while Yeddyurappa’s KJP won three seats.

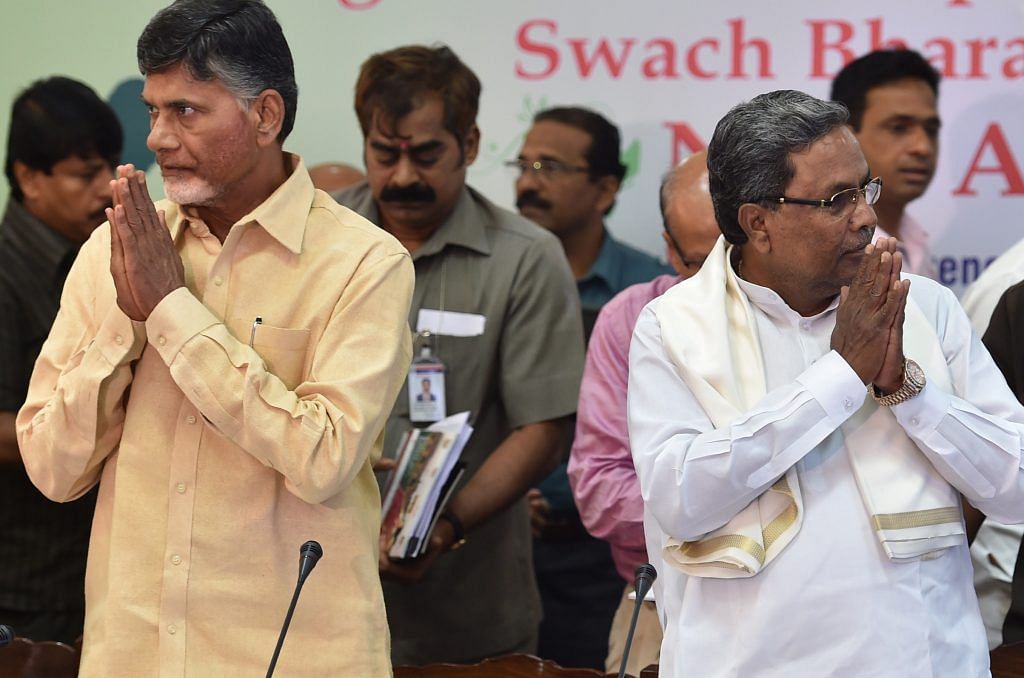

The AHINDA (Dalits, backward classes and minorities) groups that form Siddaramaiah’s vote bank are a sizeable chunk of the population, as are the Lingayats. It thus becomes a clash between these two major social groups, with their respective political icons in the Congress and BJP.

Given the sizeable Telugu-speaking population here, it remains to be seen what Chandrababu Naidu’s call to boycott the BJP after his divorce with the NDA results in.

The biggest talking point of the polls is the reemergence of the discredited Reddy brothers and their cohort. The BJP’s decision to give tickets to eight members of the Reddy family and inner circle across the state has caused considerable disquiet among party leaders and supporters, especially given the anti-corruption plank of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

People of the state have been unable to forget the reprehensible manner in which the first BJP government of Karnataka was held hostage by the machinations of the Reddys and their brazenness. Iron ore valued at Rs 35,000 crore was illegally mined, extracted, and sold to domestic and export markets through nine ports in Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh. Former Lokayukta Santosh Hegde’s scathing report of 2011 that sent shock waves in the political circles of Karnataka termed it as the “Republic of Ballari”, indicating that the Reddys had become a law unto themselves.

The visible and ugly face of the scandal, Janardhan Reddy, made several attempts to appear on podiums and rallies, before Amit Shah publicly disowned him, and also gave Ballari rally a skip. He might not be visible, but Janardhan Reddy quietly sits 45 km away from Ballari — after being debarred from campaigning there by the Supreme Court — plotting, planning and canvassing strategies for his brothers, friends and Sriramulu, and basically pulling the strings. Despite their bitter rivalry in 2011, Yeddyurappa claims now that Janardhan Reddy’s campaigning would help the party win 15 seats more in three districts of the region.

But the misfortune of the voters here is that there is hardly anything better to choose from. Six persons, against whom cases of illegal mining are still pending, have been given tickets by all the three parties. Mining mafia B.S. Anand Singh and B. Nagendra have hopped to the Congress and secured tickets. Singh is running for a third term from Vijayanagar; he has 16 cases pending against him. Nagendra, two-time MLA from Kudligi, has the highest number of cases against anyone in the scam, totaling 26. Anil Lad of the Congress has 11 cases pending, while Janardhan Reddy’s brother Somashekara Reddy, accused of bribing a judge to secure bail for his brother, has a BJP ticket.

In such a scenario, it’s a Hobson’s choice for the voters, and makes a sham of the parties’ claims of fighting corruption. Justice Hegde is livid about his voluminous report being dumped by both Congress and BJP governments. Siddaramaiah has, in fact, diluted the powers of the independent Lokayukta, and replaced it with a toothless Anti-Corruption Bureau that reports to his home minister.

Five years since the implementation of Article 371 (J), which was aimed at improving the growth of the region by investing in education and health, and creating local jobs, there is little to show on the ground. The region still lingers at the bottom on development indicators. Unemployment, malnutrition, drought, distress migration and low farm produce prices plague people here.

Two lakh acres in Raichur are parched despite the Tungabhadra River. The Karanja Dam in Bidar has reached full capacity, but work on tail-end canals and command area development are incomplete. Across the region, lack of super-specialty hospitals forces people to move to Bengaluru for treatment. The Vijayanagar Institute of Medical Services (VIMS) has been non-functional.

After the Supreme Court clamped down on illegal mining, only 10 mines are operating out of over 200 a decade ago. Closure of mines and mechanisation in existing ones have rendered lakhs of labourers jobless, leading to their migration to cities like Bengaluru for menial jobs. Lack of clean drinking water, terrible road infrastructure, acute shortage of doctors, hospitals and health facilities do not seem to feature too high in the priorities of politicians here, who are busy fighting legal cases or making caste calculations to win the polls.

Opinion polls till April-end gave a 2.3 per cent edge to the Congress, though with the re-emergence of the Reddys, the scales could tilt in the BJP’s favour. In 2014, the reunited BJP got 47 per cent of the vote, as against 45 per cent of the Congress. Just interpolating that, one might assume the BJP would secure about 23 seats, against 17 for the Congress.

Dr Vikram Sampath is a Bengaluru-based award-winning author/historian and political commentator.

This is the sixth essay in a series by the author on the upcoming Karnataka election. Read the first, second, third, fourth and fifth parts here.