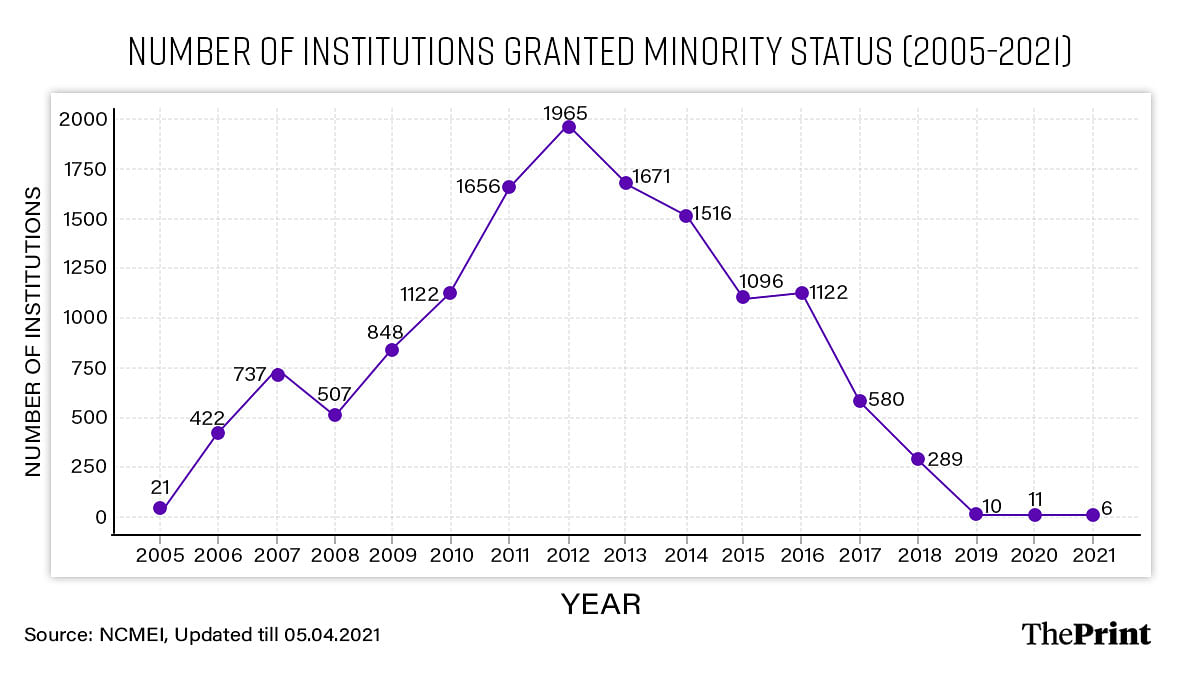

The National Commission for Minority Educational Institutions Act 2004 gives competent authorities the power to grant minority status to schools established by minority groups. Initially, less than 750 institutions were granted this status each year. However, a striking surge occurred after 2009, with the number jumping to over 1,000 annually; and a peak of almost 2,000 in 2012.

This sudden rush raises important questions: What changed in 2009 to drive this increase, and why did so many institutions suddenly seek minority status? From my analysis, some elite schools could be using their minority status as a way to avoid following the Right to Education Act, which was passed in 2009.

This trend warrants a deeper examination of the motivations behind these applications and the broader implications for educational equity.

Also read: Does Kapil Sibal want Dalits as ‘permanent bottom’? His AMU case for Muslims suggests so

Exceptions and amendments

The Right to Education Act mandated schools to allocate 25 per cent of their seats to disadvantaged communities. The Act identifies children from Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, Socially and Educationally Backward Classes (or the OBCs) and other sections of society facing various deficits as disadvantaged groups, and must be provided “free and compulsory elementary education till its completion”.

To circumvent this and preserve the elite character of schools, minority status became a godsend. This status absolves institutions from implementing the provisions of the RTE Act and reserving seats for the weaker and disadvantaged sections.

In 2010, an order was passed by the HRD ministry (now the Ministry of Education) that the rights of minority institutions are protected while implementing the provisions of the RTE Act. An amendment was made in 2012 to keep minority institutions out of the ambit of the RTE Act.

This was in line with the 93rd Amendment Act 2006, which added a sub-clause in Article 15. The new Article 15(5) states that: Nothing in this article or in sub-clause (g) of clause (1) of article 19 shall prevent the State from making any special provision, by law, for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for the Scheduled Castes or the Scheduled Tribes in so far as such special provisions relate to their admission to educational institutions including private educational institutions, whether aided or unaided by the State, other than the minority educational institutions referred to in clause (1) of article 30.

Interestingly, even some prominent schools have minority status. For example, six Delhi Public Schools (DPS) are minority institutions—three in Karnataka, two in Madhya Pradesh and one in Chhattisgarh.

I argue that this goes against the goal of the Act, which is to provide free and compulsory education to all children. There needs to be stricter rules to make sure these schools do not bypass the law, keeping access to education fair for everyone.

There is a little bit of politics and history to this whole thing. The foremost question is why the UPA-1 government brought a bill and established a body (NCMEI) to make the process of granting minority institutions easier.

After the BJP was ousted in the 2004 general elections, the Congress-led UPA started many schemes for the minorities, which is just fine. This phase of Indian political history was marked by the Ranganath Commission, the Sachar Committee and the Congress-led government in Andhra Pradesh trying to implement a 5 per cent quota for Muslims.

At the same time, the party brought The National Commission for Minority Educational Institutions (NCMEI) Bill 2004 “to safeguard the educational rights of the minorities enshrined in Article 30(1) of the Constitution”. The Bill was passed by Parliament and it became an Act in November 2004.

In the next four years (2005-2008), the number of institutions granted minority status was 21, 422, 737, and 787. The average is a little below 600. In the post-RTE period (2009-2014), the yearly numbers were 848, 1122, 1656, 1965, 1671, and 1516. The average is 1463. So the average numbers actually went up by 243 per cent, or almost two and a half times. The last available data on the NCMEI website is from 5 March 2021.

This suggests a strong correlation between the introduction of the RTE Act and the rise in minority status grants, although causality cannot be definitively established. We can easily see a pattern here, but it needs further investigation.

Also read: Muslim intellectuals defend madrasas, but their kids don’t go there. Only poor, Pasmandas do

Who are minority institutions for?

Another complexity is that minority schools are not adhering to their stated goal of imparting education to minority students.

In its 2021 report, the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) highlighted a concerning trend in minority schools. It found that 62.5 per cent of students in minority schools belong to non-minority communities. In Andhra Pradesh, Jharkhand, Punjab, Chandigarh, Chhattisgarh, Daman & Diu, Dadra & Nagar Haveli, Delhi, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Puducherry, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu Uttarakhand this number is above 70 per cent. There’s only one state where no non-minorities attend minority schools—Manipur. Additionally, only 8.76 per cent of students in these minority schools are from socially and economically disadvantaged backgrounds.

This discrepancy raises questions about the true beneficiaries of the minority status these schools hold and whether it is being used to circumvent the inclusive goals of education policies.

Interestingly, Christians constitute only 11.54 per cent of the religious population, they account for 71.96 per cent of religious minority schools. Conversely, Muslims, who make up 69.18 per cent of the minority population, represent just 22.75 per cent of these schools! This is puzzling, especially when we know that minority institutions mostly have non-minority students.

The NCPCR report argued that the exemption of minority institutions from the RTE Act has led to significant educational inequalities: “While, on the one hand, there were schools that admitted only a certain class of students, becoming cocoons populated by elites, some institutions became ghettoes of underprivileged students languishing in backwardness.”

It also recommended the need for appropriate steps to extend the provisions of the RTE to minority educational institutions or to enact a law with a similar effect to ensure the right to education of children studying in minority educational institutions.

There is an urgent need to revisit the exemptions granted to minority institutions under the Right to Education Act. While Article 30 of the Indian Constitution rightly empowers minority communities to establish and administer their own educational institutions, ensuring the preservation of their cultural, linguistic, and religious heritage, this should not impede the objectives of Article 21(A), which safeguards the fundamental right to education for every child.

I have yet to find an answer to the question of why the pace of granting minority status to institutions slowed down from 2015 onwards and why the numbers dwindled after 2019. This could be related to a new government coming to power at the centre, but it requires further scrutiny.

Dilip Mandal is the former managing editor of India Today Hindi Magazine, and has authored books on media and sociology. He tweets @Profdilipmandal. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)