In early 1990, Kashmiri Pandits, a community of proud people whose history dates back 5,000 years, were transformed into exiles overnight. Thirty years later, a film on their exodus, Shikara, written by Rahul Pandita and directed by Vidhu Vinod Chopra, has a Hindu character saying to another a line that encapsulates the community’s hope, which its every member has seen die a slow, painful death: “Dekhna Parliament mein shor machega.”

There was no shor (uproar). Not once. If there is one thing worse than losing your homeland, it is the cloak of silence that society puts over it. For as long as they can remember, no one listened to or spoke about the 3,50,000 Kashmiri Pandits who had fled the Valley by the end of 1990. A community that prided itself on contributing prime ministers and powerful officials found it had become invisible. There was complete silence, one that only now, three decades later, has partly begun to make some noise.

“Nobody bothered about us,” says Rahul Pandita, author of Our Moon Has Blood Clots; his family had to flee the Valley when he was only 14. “In Kashmir, the majority community is still in denial about what led to our exodus — that it happened because we were being hunted on the streets and inside our houses. That our neighbours, colleagues, friends turned against us. And that the rest of India just did not bother.” He hopes Shikara will change that.

Also read: Kashmiri Pandits’ return to Valley is a must for ‘idea of India’. But here are the obstacles

Can’t forget, won’t forgive

Kashmiri Pandits are used to mobility, unafraid of hardship, and always hopeful about the future. But despite having seen six waves of migration, beginning with one under Shah Mir, an invader who established Muslim rule in Kashmir, in the 14th century, the community was not prepared for its seventh. What happened on 19 January 1990 can never be forgotten; for many, it can never be forgiven.

Writer and filmmaker Siddhartha Gigoo, who was 15 when his family fled their home because the threats announced from loudspeakers were clear — reliv, seliv ya geliv (convert, leave or die) — told ThePrint: ”The land that for centuries had welcomed and sheltered zealots, scholars, mystics, conquerors, missionaries, atheists, agnostics and warriors, and allowed them to profess and practise their ideas and beliefs, had no place for its original inhabitants anymore. From 1990 to 2000, thousands perished because of lack of proper rations, water, medical care and sanitation. All deaths were unnatural and untimely. Hitherto unknown diseases struck the young and the old. Years passed. Nobody paid heed to what the Hindu exiles were made to go through in these camps. Those of us who survived were not meant to survive. We were just fortunate.”

There was a lot of learning as well, much of it bitter. As Gigoo says, when people are uprooted from their homes, they not only lose their identity and a sense of belonging, they also lose the language to communicate their pain. A new vocabulary characterised by dispossession takes birth. Quoting his father, he said: “In the camps, we learnt new words and their meanings. Ration card, migrant, tent, relief, dementia, delirium, diabetes, arthritis, tumour, sunstroke, snakebite, malignancy, heatstroke, hypertension, amnesia, myopia, thyroid, senility, cardiac arrest, depression, cholesterol, cataract, echo, viral, conjunctivitis…”

The psychological damage was enormous. Rajat Mitra, a psychologist, was referred several cases of people suffering from depression and suicidal thoughts. Mitra spoke not only to them, he also met some militants in Tihar Jail who talked to him about the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits (he writes about these experiences in a new novel, The Infidel Next Door). “The militants I talked to… welcomed the running away of the Pandits. There is virtually no guilt about their own involvement,” Mitra told ThePrint.

Also read: For Kashmiri Pandits, Azadi slogans are bringing back a three-decade old nightmare

Scarred memories

The transformation of friends and neighbours into enemies is something the Kashmiri Pandits have yet to come to terms with. Many react with deep-seated anger and resentment. Some have tried to forgive and forget. But once in a while, the wounds reopen, gaping, ugly, all too real. One such occasion was the release of Vishal Bhardwaj’s film Haider, in 2014. Many Pandits felt the film focused only on the suffering of the Kashmiri Muslims and humiliated them by staging a dance at the sacred Martand temple.

Another recent occasion was the premiere of Shikara, where director Chopra described what happened in Kashmir as “like how when two friends have a little fallout”. That was enough for people on social media to call for a boycott of the film, an increasingly default choice for every offended group, despite Chopra himself being one of the victims of the exodus.

One of the reasons the exodus has not been debated much is because resilient Pandits were largely able to face the trauma of the violence and rise above it. Instead of playing victim, which was their right, they rebuilt their lives and became engaged in carving out a new identity for themselves. But as psychologist Mitra notes, Kashmiri Pandits haven’t “worked through the grief of exodus yet and need to confront and ask from their Kashmiri neighbours why they acted the way they did”.

Also read: RSS-BJP’s new plan for Kashmir — prop up Maharaja Hari Singh as a nationalist

Recording the pain

It is something that the community has started to talk about. Director Vivek Agnihotri, of The Tashkent Files, is making a movie on the Pandits’ exodus, and has spent his last two years working on it. He and his actress wife Pallavi Joshi decided to form a tribunal and record interviews of the victims, wherever they are. “Like war crimes,” he told ThePrint. “We chased first-generation victims all over the world. We said we will go to their homes, meet them in their surroundings, be it a tin shade in Jammu or a mansion in the US. We have covered India, Europe, America, Africa. Now we are heading to the Far East, Australia and New Zealand. These aren’t interviews. These are uninterrupted recordings of their tale. We spent days with them, their families, ate with them.”

Agnihotri and his team divided the people they interacted with in three categories: first-generation victims, authors/activists/experts/officials, and the next generation. They wanted to understand what’s happening with the new generation. Are they angry? Are they hateful? By spending months with them, listening to their tales, Agnihotri and Joshi say they have seen a new side of humanity, and its potential to survive and succeed.

Others have dealt with it differently. For Rahul Pandita, writing Our Moon Has Blood Clots (2013) was a way of coming to terms with the enormous hurt but it was not an easy task. “I stopped several times, especially during passages where I had to relive the death of my brother, Ravi, and with my mother’s illness, induced by those initial years of trauma as refugee. I was in a delirium of sorts while writing. I remember holding an advance copy and trying to read it. I could not read my own book. I threw it away, I was so overcome with emotion,” he told ThePrint.

Also read: Why Kashmiri Pandits can’t return to the Valley, even if they want to

The new hope

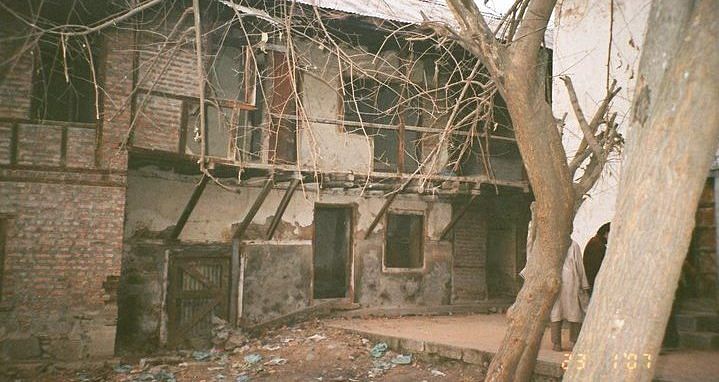

The last 30 years have been the darkest period in the history of Kashmiri Pandits. “Some are still languishing in darkness,” says Gigoo, “because they remain in camps, waiting to go back to their long-lost homes in the Valley. But most are resigned to their fate. The hope which they kept alive for more than aquarter of a century is diminishing. Now, they don’t even know what is there to go back to. Nothing remains of their homes. Not even ruins.”

A new generation has grown up in the long shadow of the exodus. Khalid Shah, who was born in 1992, grew up in downtown Srinagar, and now works in a think tank in Delhi, says he is not too well-versed with the exile of the Pandits. He has no childhood recollection of them, except for what he has heard from his mother, whose friends and teachers were Kashmiri Pandits. He knows there was deep bonhomie and syncretism between the two communities.

“My mother would partake in Kashmiri Pandit festivals and her friends would join Muslim festivities and celebrations. I have witnessed my grandfather listening to Sufi songs in praise of Lord Shiva,” Shah told ThePrint. One of the verses is still fresh in his memory: “Raaj hamsaiy ghar amuiy, az dil’uk tamanna chameim; Shiv ji paraan raam raam az diluk tamamana chalyeim.” And he has heard his uncles repeat these songs, heard them on the stereo in their cars. Such lyrics are common at weddings too, he says. Many years later, he now realises how deep the influence of Kashmiri Pandits was on the Muslim subculture in Kashmir.

But, he told ThePrint, the Kashmiri Pandits are facing an existential crisis. “If the generation of Kashmiri Pandits born in Kashmir before 1990 do not return, the community we know as Kashmiri Pandits may not exist. There are many reasons for that. One, those born after 1990, outside Kashmir, do not have a direct link with the land. Their culture and understanding of Kashmir is derived from second-hand sources and not by first-hand experience (of growing up in Kashmir). Two, the generation that took the mantle of passing on the culture and identity to the new generation is growing older now. Three, we are already seeing the culture and the identity of Kashmiri Pandits living outside Kashmir getting diluted and influenced by external factors. So, for the community, the culture and their identity to survive — it is imperative that Kashmiri Pandits of older generation, along with the younger ones, are able to return to Kashmir.”

Also read: Why Kashmiri Pandits may never return to the Valley

Hum Wapas Aayenge

And hence the renewed cry: Hum Wapas Aayenge (we will come back), given a fillip by the abrogation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status under Article 370, which in itself, has generated mixed feelings among Kashmiri Pandits. As Gigoo, who wrote his celebrated debut novel, The Garden of Solitude, in 2011, says: “People all over the country started talking of being able to buy land and property in Jammu and Kashmir. Stripped of its special status, Kashmir is now a place that belongs to everyone…’’

But can Kashmiri Pandits go there just like everyone else from India? How must they return given the history behind their forced exodus? The state certificate they had has no legal relevance now, even though its emotional relevance will never fade. It grants Kashmiri Pandits born in the Valley special status with unique rights and privileges that other Indians did not have. The special status in the erstwhile state’s constitution that failed to protect them from persecution in 1990 or guarantee their dignified return, is now gone forever. In its place exists the yearning for restitution, stronger than ever. The dream of home, to reclaim everything that was snatched from them, lingers on.

Someday, says Gigoo, those who survived, will return to their homes in Kashmir. “And that day, we shall take along all records to show our progeny the proof of our survival and of the intrepid journeys we made in exile.” For now, though, suspicion, distrust and a sense of betrayal prevails. The current generation of Pandits and Muslims don’t know each other. Kashmir is claimed by both communities.

Gigoo’s Kashmiri Muslim contemporaries, like Salman Soz, the economist and son of long-time Congressman Saifuddin Soz, believe that Kashmiri Pandits and Muslims are two sides of the same coin. “We are part of the same tradition even if our religious identities may differ.” Growing up, Soz, who was in Kashmir until 1987 — when he was in Class 10 — says the differences between the two communities were far outweighed by a common cultural and linguistic heritage. “The amity, not just between these two communities but others in Kashmir as well, was a shining example for the country.”

Soz agrees that the tragedy of the Pandits — for children to lose their language, for elders to face a strange new world, for the young to feel disempowered, to be targeted —has not elicited the kind of resolution that would make things whole for them or even partially whole. There’s a lot of lip-service, he says, but very little in terms of figuring out how Kashmiri Pandits can have their dignity fully restored. “This requires hard work, genuine bridge-building, a step-by-step painstaking effort of rebuilding trust and reconciliation — but after a lot of truth-telling in an environment that doesn’t censor feelings or thoughts. The political leadership has failed to facilitate any of this. I wonder if it might be better for Kashmiris, Pandits, Muslims, Sikhs and others to do this themselves,” Soz says, and adds: “If we hold all Kashmiri Muslims responsible for what happened to the Pandits, the whole world would be complicit in one atrocity or another.”

The eternal question is: will Kashmir be free of violence and militancy? With there be catharsis and closure? Perhaps not, but as Bertolt Brecht wrote: “In the dark times, will there also be singing? Yes, there will also be singing. About the dark times.”

The author is a senior journalist. Views are personal.