The current public disappointment with the judiciary in general and its higher echelons in particular raise two questions of public importance: (1) Should the rottenness in the judiciary structure and the termites which cause it be exposed? and (2) Does the law of contempt as currently understood require repeal or modification? On the first of these there are two conflicting views. The first is that some invisible in-house procedure for repair and rectification should exist within the judicial family and the misbehavior of judges should not be publicly exposed. If criticism of judges becomes a regular routine, courts will be stripped of their dignity, solemnity and capacity to inspire fear. This will lead to the collapse of the judicial system. Doubtless this argument must be given due weight. The people of this country have for long accepted this limitation on their freedom of conscience and free speech. There is also the lurking fear of the contempt power of judges descending on the head of the critic.

Unfortunately, the hope that in the long run things will somehow work out well has not materialised and, as observed by the Venkatachaliah Commission, cases of judicial misbehaviuor are becoming more and more common. Prof. Harold Laski, the political theorist and economist, advised us that the manner in which the nation dispenses justice in the courts, the way in which courts discharge their functions, and the methods by which they are chosen are problems that lie at the heart of political philosophy. When we know how a nation doles out justice we know with some exactness the moral character to which it can pretend. To this I must add that a vibrant democracy must extend the application of the rule of accountability to all its branches.

Judge Jerome Frank, in his well-known book Courts on Trial, struck a conclusive blow for free exposure when he said: “It can ever be unwise to acquaint the public with the truth about the workings of any branch of government. It is wholly undemocratic to treat the public as children who are unable to accept the inescapable shortcomings of man-made institutions. The best way to bring about the elimination of those shortcomings of our judicial system that are capable of being eliminated is to have all our citizens informed as to how that system now functions. It is a mistake, therefore, to try to establish and maintain, through ignorance, public esteem for our courts.”

Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer, in his inimitable style, has told us: “To wash institutions in the acid of truth is the way to remove the dross of lies. ‘Know ye the truth and the truth shall make you free.’ To suppress critical expression beyond minimal reticence parameters is to summon severe explosion of popular rage beyond the ineffectual power of contempt.” He too has expressed the wish that “before long a National Commission beyond the incestuous composition of and interaction among judges themselves, is the desideratum. Statesmanship summons high-level participation in such a performance commission.

The way in which ‘Judge and Co.’ (philosopher and social reformer Jeremy Bentham’s phrase for the judiciary) is run is a matter of public interest and national security”.

Throughout my professional career I have fought for judicial independence and integrity. That public confidence has not completely eroded is a tribute to this institution. But I will be less than honest if some truths are not politely uttered. Two judgments delivered in July have left me in a state of mental turmoil. In the first, a well-reasoned and sober judgment of a single judge of the High Court of Delhi was reversed [UOI v. Prakash P. Hinduja; Appeal (Crl) 666/2002]. The Supreme Court while reversing it pronounced the High Court judgment to be confusing and contradictory. It would doubtless be a black mark against the poor High Court judge if he ever comes to be considered for promotion to the Supreme Court.

But the unpardonable error of the Supreme Court is that in each of those paragraphs in which the Supreme Court discovered the High Court’s findings, there were in fact no findings but only a recital of the arguments of the Solicitor-General which the High Court ultimately rejected. The bar had made no such argument and the Supreme Court cannot even plead that bad advocacy led it to this serious lapse.

The bar had even provided written submissions. It was a reserved judgment and not an oral judgment. How two Supreme Court judges could be guilty of such culpable misreading of the record is beyond comprehension. True, a review petition is pending, in which it has been pointed out on behalf of the petitioners that the Supreme Court owes an apology to the High Court judge. But the secret chamber hearing is not likely to bring justice either to the party or to the High Court. This obviously is not the kind of misbehaviour that attracts an impeachment procedure but it is certainly conduct which brings justice into disrepute and lowers the dignity of the Supreme Court.

In another instance, the Supreme Court reserved a Bombay High Court judgment which rightly held that a management order which grounds air hostesses when they cross the age of 50, consider them as cabin crew up to the age of 58 [Air India v. Nargesh Meerza; 1981 Air 1829, 1982 SCR (1) 438]. When the poor women fly they get about Rs 80,000 a month and when they work on the ground they hardly get about one-fourth that amount. How can we reconcile ourselves to this kind of male chauvinism? The United Nations tells us to remove all forms of discrimination against women and Article 51A of the Constitution outlaws all practices derogatory to women. Women will not look agile and pretty at 50 but nobody is supposed to complain about the sloppy attire, bulging bellies and foul odour of males over 50.

Judges are made to sit on benches before which all sorts of matters turn up. Some of them arise in areas of law about which one or more or all the judges on the bench have not the faintest idea. I have had the misfortune of appearing before benches in serious criminal cases where not one of the judges could claim familiarity with criminal law. Counsel even find it difficult to decide how much enunciation of the relevant law they must attempt or when to stop in the belief that their argument has at last been understood. It is easy to deal with a loquacious judge but the ignorant usually adopt a sphinx-like posture. Repeated suggestions that matters relating to specific branches of the law be put before judges who are experts in those areas have fallen on deaf ears. Only those sitting in court observe the frequent miscarriages of justice; these go unnoticed by others and do not even evoke a protest.

This is part of ThePrint’s Great Speeches series. It features speeches and debates that shaped modern India.

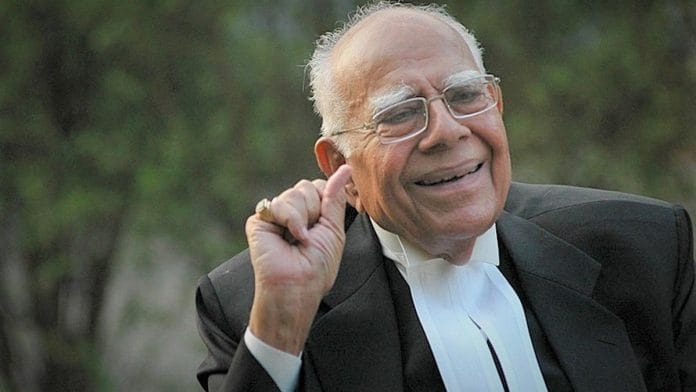

Going by the headline, India is an immoral country. Well said, Mr Ram J.