I believe it will not be out of place to mention that the change in the political situation has greatly affected the temper and nature of the work which we have undertaken. The scales in which the educational problems were weighed by this Board until now have grown out of date. New scales with new weights will have to be substituted. The dimensions of the national problems of the day cannot now be judged by the measurements which have been employed so far. The new aspirations of the New India will require fresh outlook and new measures to tackle its problems.

With whatever depth of vision and sympathetic imagination the Board might have tackled the educational problems in the past, it could not escape the fact that there was no free National Government to support it. In spite of its desire to have the fullest scope it had to keep itself somewhat in restraint. Now things have changed. The nation, about the educational problems of which you are going to deliberate, has its own government at your entire disposal. The Government in its turn expects that you, too, offer your deliberations with the same tenacity of purpose and breadth of vision as are guiding the administration today.

Probably the most valuable service rendered by the Board was the preparation of the scheme of Basic Education in 1944. It was the first occasion in the history of British India when the problem of elementary education was presented in its true aspect. A scheme was then initiated which contained the elements of broad outlook and bold action, the two things which were least expected in the then prevailing circumstances.

In connection with the scheme of the Basic Education, the question of religious instruction had cropped up at the time. Two committees of the Board pondered over it but they were unable to come to an agreed decision. I should like this question to be reconsidered in the light of the changed circumstances. For our country, this question has a special importance.

It is already known to you that the nineteenth-century liberal point of view concerning the imparting of religious education has already lost weight. Even after the World War I, a new approach had begun to assert itself and the intellectual revolution brought about in the wake of the World War II has given it a decisive shape. At first it was considered that religions would stand in the way of the free intellectual development of a child but now it has been admitted that religious education cannot altogether be dispensed with. If national education was devoid of this element, there would be no appreciation of moral values or moulding of character on human lines. It must be known to you that Russia had to give up its ideology during the last World War. The British Government in England had also to amend its educational system in 1944.

So far as India is concerned, the problem presents itself in an entirely different shape. Europe and America felt the need of religious education as it was observed that without religious influences people became over-rationalistic. But in so far as they are working in Indian life, we have to face the other side of the medal. We have no fear that people will become ultra-rationalists. On the contrary we are surrounded by over-religiosity. Our present difficulties, unlike those of Europe, are not creations of materialistic zealots but of religious fanatics. If we want to overcome them, the solution lies not in rejecting religious instruction in elementary stages but in imparting sound and healthy religious education under our direct supervision so that misguided credulism may not affect the children in their plastic stage.

It is obvious that millions of Indians are not prepared to see that their children are brought up in an irreligious atmosphere and, I am sure, you, too, will agree with them. What will be the consequence if the Government undertake to impart purely secular education? Naturally, people will try to provide religious education to their children through private sources. How these private sources are working today or are likely to work in future is already known to you. I know something about it and can say that not only in villages but even in cities, the imparting of religious education is entrusted to teachers who, though literate, are not educated. To them, religion means nothing but bigotry. The method of education, too, is such in which there is no scope for broad and liberal outlook.

It is quite plain, then, that the children will not be able to drive out the ideas infused into them in their early stage, whatever modern education may be given to them at a later stage. If we want to safeguard the intellectual life of our country against this danger, it becomes all the more necessary for us not to leave the imparting of early religious education to private sources. We should rather take it under our direct care and supervision. No doubt, a foreign government had to keep itself away from religious education. But a National Government cannot divest itself of undertaking this responsibility. To mould the growing mind of the nation on the right lines is its primary duty. In India, we cannot have an intellectual mould without religion.

But if religious instruction is to be a part of basic education, what will be its proportion? How is it to be managed? These are questions which are to be thoroughly considered. Indeed, there will be difficulties in the way. A solution will have to be found. But I need not go into details. If the main issue is settled, details can be tackled later on. In any case I request you to appoint a committee to go into the question ab novo. It may be authorised to send its recommendations directly to the Government.

There is another problem on which you have to take a final decision now. What is to be the medium of instruction in our educational institutions? I am sure there are two things with which you will agree. First, that in future, English cannot remain the medium of instruction. Secondly, whatever the change may be in this direction, it should not be sudden but gradual. In my opinion, so far as higher education is concerned, we should come to the decision that the status quo may be preserved for five years. But along with it a provision may be made by the universities for the coming change. I should like you to make your suggestions to the Government after due deliberation.

But in this connection a fundamental question arises with regard to Indian languages. How is the change to be brought about? Is university education to be imparted through a common Indian language or the provinces may be given an opportunity to have their own regional languages for university teaching?

English was a foreign language. We were greatly handicapped by having it as our medium of instruction. But we were also greatly benefited in one way that all the educated people in the country thought and expressed themselves in the same language. It cemented the national unity. It was such a great boon to us that I should have advocated its retention as the medium of instruction, had it not been fundamentally wrong to impart education through a foreign language.

But obviously, I should desist from offering this advice. I put it to you, if only till recently a Madrasi or a Punjabi or a Bengalee felt no difficulty in receiving education through a foreign language, why he should be handicapped if he were to be educated through one of the Indian languages. If instead of English we adopt an Indian language, we shall certainly be able to retain the same intellectual unity which was created for us by the English language. But if we fail to substitute an Indian language for English our intellectual unity will certainly be affected.

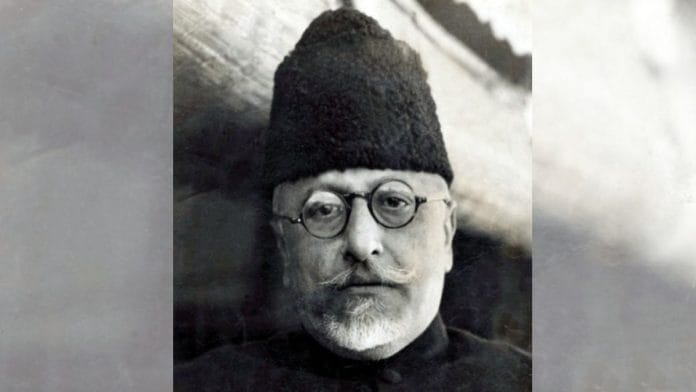

Editor’s Note: This is an abridged version of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad’s presidential speech at the 14th session of the Central Advisory Board of Education, New Delhi, delivered on 13 January 1948. Read the full speech here.

This is part of ThePrint’s Great Speeches series. It features speeches and debates that shaped modern India.