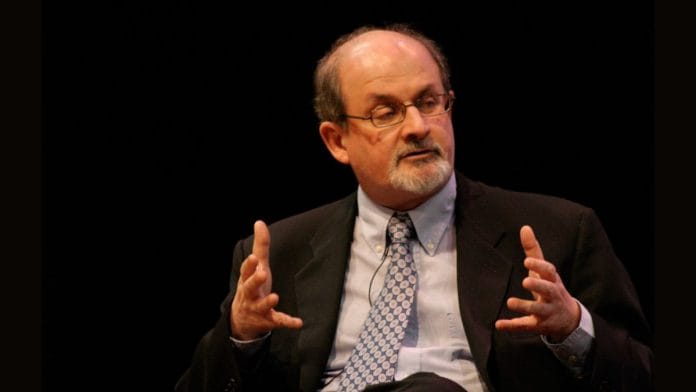

To stand in this house is to be reminded of what is most beautiful about religious faith: its ability to give solace and to inspire, its aspiration to these great and lovely heights, in which strength and delicacy are so perfectly conjoined. In addition, to be asked to speak here on this day, the fourth anniversary of the notorious fatwa of the late Imam Khomeini, is a particular honour.

When I was an undergraduate at this college, between 1965 and 1968, the years of flower-power and student power, I would have found the notion of delivering an address in King’s Chapel pretty far-out, as we used to say; and yet, such are the journeys of one’s life that here I stand.

I am grateful to the Chapel and the college for extending this invitation, which I take as a gesture of solidarity and support, support not merely for one individual but, much more importantly, for the high moral principles of human rights and human freedoms that the Khomeini edict seeks so brutally to attack. For just as King’s Chapel may be taken as a symbol of what is best about religion, so the fatwa has become a symbol of what is worst.

It feels all the more appropriate to be speaking here because it was while in my final year of reading history at Cambridge that I came across the story of the so-called satanic verses or temptation of the Prophet Muhammad, and of his rejection of that temptation. That year, I had chosen as one of my special subjects a paper on Muhammad, the rise of Islam, and the caliphate.

So few students chose this option that the lectures were cancelled. The other students switched to different special subjects. However, I was anxious to continue, and Arthur Hibbert, one of the King’s history dons, agreed to supervise me. So as it happened I was, I think, the only student in Cambridge who took the paper. The next year, I’m told, it was not offered again. This is the kind of thing that almost leads one to believe in the workings of a hidden hand. The story of the ‘satanic verses’ can be found, among other places, in the canonical writings of the classical writer al-Tabari.

He tells us that on one occasion the Prophet was given verses which seemed to accept the divinity of the three most popular pagan goddesses of Mecca, thus compromising Islam’s rigid monotheism. Later he rejected these verses as being a trick of the devil saying that Satan had appeared to him in the guise of the Archangel Gabriel and spoken ‘satanic verses.’ Historians have long speculated about this incident, wondering if perhaps the nascent religion had been offered a sort of deal by the pagan authorities of the city, which was flirted with and then refused.

I felt the story humanized the Prophet, and, therefore made him more accessible, more easily comprehensible to a modern reader, for whom the presence of doubt in a human mind, and human imperfections in a great man’s personality, can only make that mind, that personality, more attractive.

Indeed, according to the traditions of the Prophet, even the Archangel Gabriel was understanding about the incident, assuring him that such things had befallen all the prophets, and that he need not worry about what had happened. It seems that the Archangel Gabriel, and the God in whose name he spoke, was rather more tolerant than some of those who presently affect to speak in the name of God. Khomeini’s fatwa itself may be seen as a set of modern satanic verses. In the fatwa, once again, evil takes on the guise of virtue; and the faithful are deceived. It’s important to remember what the fatwa is.

One cannot properly call it a sentence, since it far exceeds its author’s jurisdiction; since it contravenes fundamental principles of Islamic law; and since it was issued without the faintest pretence of any legal process. (Even Stalin thought it necessary to hold show trials)! It is, in fact, a straightforward terrorist threat, and in the West it has already had very harmful effects. There is much evidence that writers and publishers have become nervous of publishing any material about Islam except of the most reverential and anodyne sort.

There are instances of contracts for books being canceled, of texts being rewritten. Even so independent an artist as the filmmaker Spike Lee felt the need to submit to Islamic authorities the script of his film about Malcolm X, who was for a time a member of the Nation of Islam and performed the hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca. And to this day, almost one year after the paperback of The Satanic Verses was published (by a specially constituted consortium) in the United States, and imported into Britain, no British publisher has had the nerve to take on distribution of the softcover edition, even though it has been in the bookstores for months without causing the tiniest frisson.

In the East, however, the fatwa’s implications are far more sinister. ‘You must defend Rushdie,’ an Iranian writer told a British scholar recently. ‘In defending Rushdie you are defending us.’ In January, in Turkey, an Iranian-trained hitsquad assassinated the secular journalist Ugur Mumçu. Last year, in Egypt, fundamentalist assassins killed Farag Fouda, one of the country’s leading secular thinkers.

Today, in Iran, many of the brave writers and intellectuals who defended me are being threatened with death-squads. Last summer, I was able to participate in a literary seminar staged in a Cambridge college and attended by scholars and writers from all over the world, including many Muslims.

I was touched by the friendship and enthusiasm with which the Muslim delegates greeted me. A distinguished Saudi journalist took my arm and said, ‘I want to embrace you because you, Mr Rushdie, are a free man.’ He was fully aware of the ironies of what he was saying. He meant that freedom of speech, freedom of the imagination, is that freedom which gives meaning to all the others. He could walk the streets, get his work published, lead an ordinary life, and did not feel free, because there was so much he could not say, so much he hardly dared to think. I was protected by the Special Branch; he had to watch out for the Thought Police.

Today, as Professor Fred Halliday says in this week’s New Statesman & Society, ‘the battle for freedom of expression, and for political and gender rights, is being fought out not in the senior common rooms and dinner tables of Europe, but in the Islamic world.’ In his essay, he gives some instances of the way in which the case of The Satanic Verses is being used as a symbol by the oppressed voices of the Muslim world. One of the many Iranian exile radio stations, he tells us, has even named itself Voice of the Satanic Verses. The Satanic Verses is a committedly secular text that deals in part with the material of religious faith. For the religious fundamentalist, especially, at present, the Islamic fundamentalist, the adjective ‘secular’ is the dirtiest of dirty words.

But here’s a strange paradox: in my country of origin, India, it was the secular ideal of Nehru and Gandhi that protected the nation’s large Muslim minority, and it is the decay of that ideal that leads directly to the bloody sectarian confrontations which the subcontinent is now witnessing, confrontations that were long foretold and could have been avoided, had not so many politicians chosen to fan the flames of religious hatred.

Indian Muslims have always known the importance of secularism; it is from that experience that my own secularism springs. In the past four years, my commitment to that ideal, and to the ancillary principles of pluralism, skepticism, and tolerance, has been doubled and redoubled. I have had to understand not just what I am fighting against— in this situation, that’s not very hard—but also what I am fighting for, what is worth fighting for with one’s life.

Religious fanaticism’s scorn for secularism and for unbelief led me to my answer. It is that values and morals are independent of religious faith, that good and evil come before religion: that— if I may be permitted to say this in the house of God—it is perfectly possible, and for many of us even necessary, to construct our ideas of the good without taking refuge in faith. That is where our freedom lies, and it is that freedom, among many others, which the fatwa threatens, and which it cannot be allowed to destroy.

This is part of ThePrint’s Great Speeches series. It features speeches and debates that shaped modern India.

This speech has been excerpted from ‘The Great Speeches of Modern India’ by Rudrangshu Mukherjee, with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This speech has been excerpted from ‘The Great Speeches of Modern India’ by Rudrangshu Mukherjee, with permission from Penguin Random House India.

Though I agree with rushdie here. But there is no way one can develop a sense of good and evil without religion. Thats a task noone has achieved yet. Anyone who claims it forgets that his ideals are shaped either by the religions around him or by the culture which is imbued with religion without him knowing it.