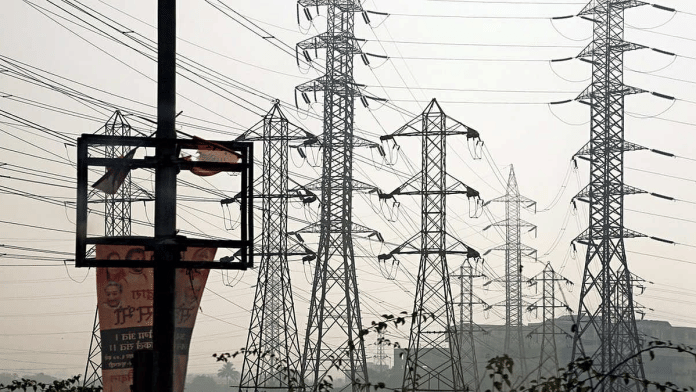

This year has seen unprecedented power demand in India. Scorching summers and delayed monsoons have meant that people have been using more electricity than ever before. Take the case of Karnataka. The state has been facing a shortfall of approximately 1,500-2,000 MW of power, and has had to devise mechanisms to find power elsewhere. As a consequence, citing public interest, the Karnataka government invoked Section 11 of the Electricity Act on 14 October. Private generation companies are now forced to supply power to the state discom. Karnataka is not the first state to take such an action, nor is it the first time it has taken such an action. The situation once again reminds us that our priority should be to plan for the inevitable increase in demand. Resorting to “public interest” as a tool for crisis management is not sustainable.

Also read: Something worrying is happening in economy. Modi govt must shift focus to commerce ministry

Better procedure for Section 11

Under Section 11 of the Electricity Act, the government can force a generation company to operate and maintain a station as per its requirements. When the government does this, it is required to compensate the generation company for the adverse financial impact. One can imagine that such a diktat can disrupt the plans of private sector producers, and make private parties reluctant to invest, or ask for a higher rate of return. Fundamentally, such an action impinges on the rights of other private parties. This power should, therefore, be used sparingly.

The Electricity Act does specify that the government can do this only under “extraordinary circumstances”. The Act defines ‘extraordinary circumstances’ as circumstances arising out of threat to security of the State, public order or a natural calamity or such other circumstances arising in the public interest. The Act leaves it to the discretion of the government to decide what is public interest and whether a particular circumstance is in public interest. The idea of public interest is not new in India, and has been used often to allow the state to take decisions that may go against legitimate private interests.

While the government is required to compensate private generators for the loss that they incur, it is quite possible that there may be little agreement on what a fair compensation should be. The Electricity Act is sufficiently vague on how such compensation should be arrived at. In 2015, the government of Karnataka had invoked Section 11 owing to shortage of power, and fixed a provisional tariff of Rs 5.08 per unit. The Electricity Commission decided in 2016 that the generators should be compensated at the rate of Rs 4.67 per unit. The Karnataka Electricity Regulatory Commission rejected the petition of the private parties for the higher tariff. Lack of clarity in the determination of compensation leads to disputes, taking away significant time and resources of parties that may be better spent in augmenting physical and human productivity. The state distribution companies are known for not paying generators on time in normal circumstances. Why should we expect that timely compensation will ensure in crisis times? Because Section 11 impinges on the rights of private parties, these powers are meant to be exercised as an exception rather than the rule.

This is best done if the law requires the government to follow a process where it is not enough to demonstrate the difficulty of the present situation. While the Karnataka shortage of power is real, and inability to meet power demand will lead to serious difficulties, this should not be sufficient to invoke Section 11.

In light of these challenges, it is crucial to consider the government’s new hydro and coal allocation norms that aim to enhance power production capacity and address the ongoing shortages effectively.

The government should be required to do two other assessments: that of the relative costs and benefits of a specific action, and whether the decision was carried out transparently and with adherence to due process. The government should also be asked to justify that all other options to resolve the problem have been exhausted in the short-run, and that it has designed policy measures that will ensure that it will be better prepared to deal with shortages in the future. At present, these considerations are orthogonal to the invoking of Section 11.

Also read: Telcos urge TRAI to ignore start-ups’ objections as tussle over network usage fee for OTTs continues

Solving for shortages

This has been a year of a surge in demand for power across the country. In August, the country saw a power shortage of over 4 per cent of the peak demand. Coal plants across the country have been operating at full capacity using imported coal, also because of government diktat. It is likely that next year will be no different. We may have to gear ourselves for crisis mode during summer months year after year. This begs the question – why is it that our chances of finding ourselves in a similar position are so high?

There may be several reasons – from the lack of additional coal supplies, to the mismanagement of existing ones. While renewable power is able to meet day time shortages, the shortage in thermal power exposes us to shortages in the night time. As Jonathan Kay has argued, generation companies in India have lacked the resources or the incentives to take proactive measures to avoid blackouts. In addition, our policy environment has not been able to create a market for storage, or for trading of power. The resolution of our power crisis requires an understanding of why these markets have not taken off. The true interests of the Indian public may lie in that understanding.

Renuka Sane is research director at TrustBridge, which works on improving the rule of law for better economic outcomes for India. She tweets @resanering. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)