On 5 November, the National Security Act came into force in Goa for three months. The Act, usually reserved for terrorists and threats to national security, arms the state with powers of preventive detention to tackle what Chief Minister Pramod Sawant calls a crime wave driven by “migrants.”

This is neither the first time Sawant has blamed migrants for rising crime in India’s smallest state, nor will it be the last.

This casual scapegoating of migrants, in fact, goes to the heart of a central tension in Goa. But first, a look at some of the events leading up to the NSA being imposed in the state.

Also Read: Goa’s digital nomads get a reality check—working from paradise needs more than just good vibes

The trigger and the tension

The government had applied for the NSA in late September, immediately after a brutal attack on social activist and politician Rama Kankonkar. On 18 September, Kankonkar was dragged out of a restaurant in Caranzalem at midnight by seven men, beaten with a cycle chain, stripped of his shirt, and smeared with cow dung. The entire assault was captured on CCTV. As they hit him, the attackers taunted, “Do you want to become Goa’s rakhondar (protector)?”

The attack triggered an immediate political crisis. Even though most of the accused were apprehended the following morning, Goa’s opposition parties rallied within hours. Members of the Congress, AAP, Goa Forward Party, and Revolutionary Goans Party attempted to march to the Chief Minister’s residence. When stopped, they blocked the Panaji bridge, causing massive traffic breakdowns, and demanded the immediate arrest of the mastermind as well as the formation of a special task force.

Almost a month later, upon his discharge from hospital, Kankonkar alleged that he suspected Sawant of being involved in the attack — a charge the Chief Minister dismissed as “sensationalism”. His wife, Rati Kankonkar, later accused a Panaji police inspector of leaking her husband’s confidential statement to the media and demanded an independent investigation.

The Kankonkar assault was the straw that broke the camel’s back. It came against a backdrop of mounting public alarm over crime. Earlier in the year, armed robbers had tied up 77-year-old industrialist Jaiprakash Dempo and his septuagenarian wife at their Dona Paula residence, ransacking their home. There have been double murders, gang clashes, shootings over sand extraction, and extensive land grab cases involving forged documents.

A few days prior, Arvind Kejriwal, national convenor of the Aam Aadmi Party posted on X: “Murders, shooting, daylight robbery. What is happening in Goa? This is a total collapse of law & order in Goa under BJP… BJP has turned Goa into a lawless state.” In response, the BJP Goa handle snapped back with usual aggression, asking Kejriwal to mind his own business.

But the pressure to deliver on crime has slowly been mounting on Sawant. The India Justice Report 2025 ranked Goa last among small states in overall justice delivery – last in police, prisons, judiciary, and human resources. Sawant rejected the report outright, labelling it “not an authentic government document”.

And then came the finger-pointing at migrants. It’s a strategy that is conveniently trotted out whenever necessary: Sawant had accused them in November 2024 and before that, on the occasion of Labour Day in 2023, said that workers from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar were responsible for 90 per cent of crimes in Goa. (Sawant had walked back his remarks a few days later, when he was checked by alliance partners of his own party, the BJP, and Bihar’s deputy Chief Minister, Tejashwi Yadav.)

But among the public, resentment toward ‘outsiders’ has altogether different roots.

What’s really making people angry?

The real and present animosity is against wealthy buyers from Delhi, Mumbai, and Bengaluru, who have bought up large tracts of land and made it unaffordable for local Goans. And then there are the tourists, several of them from north and south India, whose disgusting, licentious behaviour, especially with women, has been a sore spot among Goans for years. Yet that fury rarely touches them.

Instead, it gets channelled downward, against the poorest and most vulnerable workers from the cowbelt — people who represent vote banks for almost all politicians, but who they can never be seen defending publicly. Migrants, unsurprisingly, belong nowhere.

In Goa, the BJP and the anti-BJP alliance — which includes Congress, the Revolutionary Goans Party (RGP), and the Goa Forward Party — are united in targeting migrants. The alliance was announced around Diwali and meant to project unity against the BJP ahead of the state assembly elections in 2027. But days later, Manoj Parab, who heads the RGP, threatened to reconsider the coalition. “If our partners keep appeasing migrants at the cost of Goan interests, we will walk away from this alliance,” Parab said. The RGP, which many liken to the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena, had won one seat in the 2022 elections, rising on the back of anti-migrant rhetoric.

There’s an empty PWD ground close to Porvorim’s under-construction flyover. Over the past year, I’ve watched men with heavy backpacks trudge up and down these roads each day, standing around the ground, waiting. The ground is the equivalent of what is called a “labour chowk” in north India, and these men are masons, painters, or plumbers who can be hired for odd jobs. On the evening I stop to talk to them, the fact that they’re still there means they haven’t found work for that day.

These people, who keep Goa running, earn about Rs 8,000 a month, and live four people to a room, are the state’s supposed security threats.

Conveniently invisible

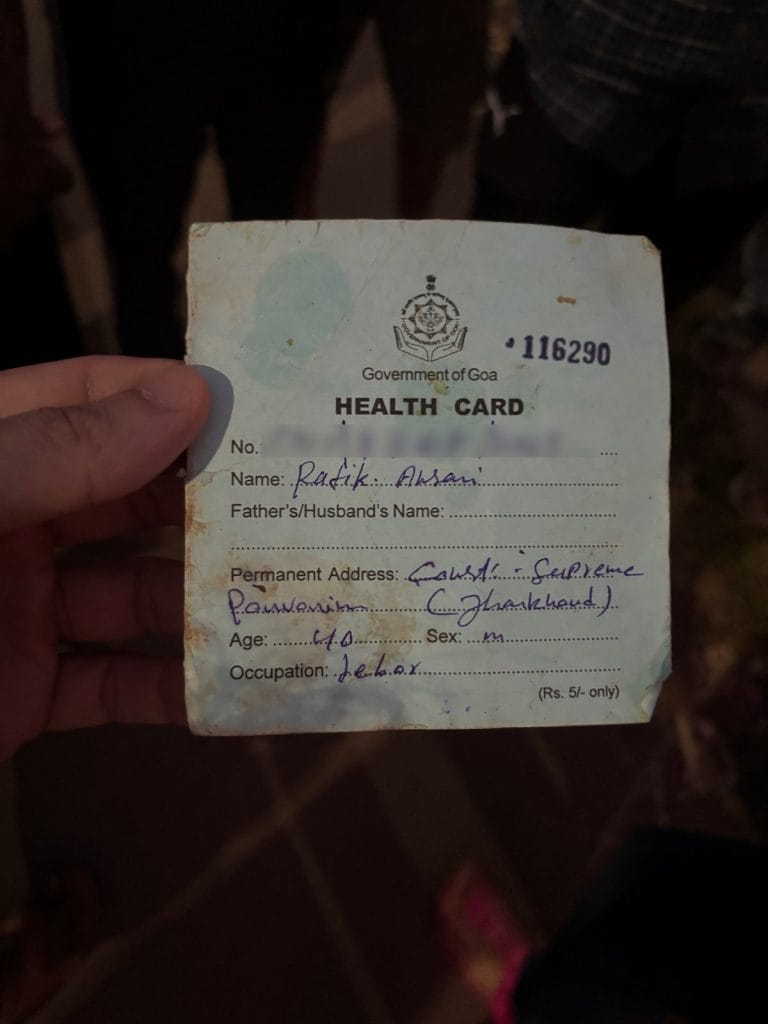

Sanjay Das, 50, is from a Jharkhand village that is two days and three trains away from Goa. I ask Das what he thinks of the Chief Minister linking crime to migrants. He laughs, dryly: “Why will someone come so far to rob or murder or commit other crimes?”

It’s a reasonable question. Das, who has been coming to Goa for the last few years, says it doesn’t matter who commits the crime. It’s people from UP and Bihar who get blamed. “Why don’t you check the pockets of people here, they barely have Rs 10 on them,” he says.

Another man chimes in: it’s usually the other way around, they are the ones falling victim. Sometimes contractors hire them but don’t pay them fairly; sometimes, they don’t pay them at all. “The police won’t even listen to us,” he says.

Vulnerable workers with no association, no union, no protection, and no voice make for perfect scapegoats because of their invisibility. When the state needs someone to blame, it picks people who can’t fight back.

Another mason from Jharkhand, Mohammad Kalimuddin, 60, puts it plainly: “Hum keede-makodon ki zindagi ji rahe hain. Labour log aapka maar kha sakte hain. Lekin woh kabhi maarenge nahi”— We live like insects. Labourers can take your beatings, but they will never strike.

A sympathetic editorial in Goemkarponn last week looked at the plight of migrants. “Migrants form the backbone of the state’s workforce, from construction and hospitality to waste management and domestic help. To frame them primarily through a lens of criminality risks not only alienating a large section of residents but also undermining a rational debate about safety and governance,” it said.

Suraj Nandrekar, the newspaper’s editor and author of the piece, is blunt about the economic reality that politicians ignore.

“Goans are not interested in pursuing skilled work like masonry, plumbing, or electrical work,” he tells me in an interview. “We don’t get carpenters, or fruit and vegetable vendors. You can’t blame migrants for everything. How can Goa survive without them? If there is demand, there will be supply.”

The real problem, he argues, is that authorities don’t take verification seriously. “A proper database of workers, linked with their employers, would help authorities track movement, deter criminal activity, and improve accountability. But the success of such a system depends entirely on fair and consistent implementation.”

Also Read: Goa’s ‘taxi mafia’ crisis is rooted in broken promises. Tourists, residents pay the price

The politics of blame

A slow consensus has been building against migration over the last few years, aided by the media and popular culture. Kaustubh Naik, a doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania who studies Goa, has been observing this trend for over a decade.

“In TV and local newspapers, crime reports will always mention where the accused or criminals are from, say, native of Chhattisgarh,” he tells me. “It stems from the notion that ‘we,’ i.e. Goans, are civilised, while the source of the crime is elsewhere. The equating of crime with migrants is now a narrative practice.”

This isn’t new; the caricaturing of “outsiders”, he points out, has existed even in tiatr (local Goan theatre), where Banjara women often get lampooned. One song even parodies migrants and suggests that BJP MLA Michael Lobo patronises them (even though Lobo has consistently “expressed concern” against the influx). Naik says there is also a sense that “outsiders” don’t fit into the Goan way of life. “So it is built into the Goan political rhetoric.”

The irony is that Goa’s economy is heavily reliant on remittances from Goans who migrated abroad. “Lots of Goans are also migrants. But they tend to be the most vociferous defenders of Goa,” he notes. In the Goan imagination, external migration is viewed as a measure of desperation. “But the migrant to Goa is seen as more opportune. It is easy to hate horizontally.”

For Naik, the invocation of the NSA “shows a government in crisis”. That’s a sentiment many in Goa share, including Carlos Ferreira, Aldona Congress MLA , former Advocate General of Goa, and former Assistant Solicitor General of India. He points out the legal fragility of the NSA’s invocation. “Whenever anyone is detained under NSA, there has to be a live link,” Ferreira tells me. “You can’t link it to something that happened three months ago. It will collapse at its foundation.”

Drawing on his six years as a public prosecutor, Ferreira claims that 80 per cent of crimes were committed by outsiders, including fist fights, stone throwing, and murders. But he’s also clear about the double standards at the heart of these measures. According to him, there are large numbers of illegal encroachments on comunidade land by migrants, who stand to benefit from recent land bills introduced in the state.

“On the one side, the government is blaming them, and on the other side regularising them. This is political hypocrisy, because they are building a migrant vote bank,” he said.

But then again, hypocrisy makes the world go around. Meanwhile, the NSA will be in force for three months. During that time, men like Sanjay Das will continue to show up at the labour chowk, tools on their backs, hoping for a day’s work. They’ll keep Goa running, building its homes, cooking its food, and cleaning its streets. And when the NSA expires and the panic subsides, they’ll still be here, doing the work no one else wants to do. Still invisible, still the enemy.

This article is part of the Goa Life series, which explores the new and the old of Goan culture.

Karanjeet Kaur is a journalist, former editor of Arré, and a partner at TWO Design. She tweets @Kaju_Katri. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)