Last week, world leaders gathered at the United Nations to be schooled by President Donald Trump on the irrelevance of the UN, typified by a broken escalator and failed teleprompter, and the greatest “con job” unleashed on the world—climate change. Watching last week’s events, one can easily forget that it was only a decade ago, when world leaders signed up to “sustainable development goals” (SDGs) at the same forum in 2015 and months later adopted the Paris Agreement to limit global warming. The World, it appeared, was ready to commit to a set of universal goals to improve the human condition for all.

Arguably, this global commitment to the SDGs was the real con job. The SDGs and Paris Agreement were dead on arrival, defanged and de-funded before they could take off. Trump 2.0’s rejection of the SDGs and withdrawal of aid, including the gutting of USAID, is merely the final nail in the coffin.

According to estimates, meeting the SDGs and making good on climate commitments by 2030 requires an additional spending of $ 4 trillion per year—about 3 per cent of global GDP. To mobilise funds, billions of dollars provided by development aid were to be deployed with the explicit aim of leveraging trillions in private funding. In practice, these global commitments remained confined to nice slogans that never delivered. The much-hyped “Billions to Trillions” vision generated peanuts.

Meanwhile, global aid is projected to reduce dramatically – by up to 22 per cent from current levels, according to a report by McKinsey & Co. Beyond the funding gap, the rise of de-globalisation, hyper-nationalism, and “America first” politics has led to the rejection of the very idea of global cooperation needed to achieve universal development goals. In that sense, global development, as several commentators have remarked, is indeed dying.

But if something is dying, it is worth asking, does it matter? What do we lose if we let it die?

An existential crisis

Led by the troll army, many in India are celebrating the death of global development. Good riddance, they say, to a “Soros-funded, anti-national, leftie” project. What this hyperactive, narrow, and petty social media gang misses is that India (and indeed many other developing countries) has long been an active contributor to the global development agenda, participating in, debating, and shaping its discourse, knowledge and practice to serve its own interests.

In a new book, Apostles of Development, historian David Engerman traces the life and work of six economists from South Asia, including Jagdish Bhagwati, Manmohan Singh and Amartya Sen, to offer a vivid account of how their ideas, debates, and critiques shaped development practice from international trade to welfare. Their primary preoccupation was to improve the lives of the poor in their nations. Democratising development and its underlying knowledge base was essential to this endeavour. Global agencies from the World Bank to the UN were sites where orthodoxies were contested, and ideas emerging from these contestations were put into practice.

This cross-border flow of knowledge and ideas is the most powerful reason why global development cooperation matters and must be revived. After all, there is no magic formula for development. Ideas, evidence, and global experience are critical to enabling countries to chart their own course. There is no better example of this than our own 1991 reforms. Consensus for these reforms was built on the back of ideas and debates in the global arena, which our reformers both engaged in and influenced.

As the world faces an uncertain future, the development challenge has only grown. Ironically, in this moment of deglobalisation and hyper-nationalism, the problems we confront—from climate change to pandemics to technological disruptions— are more global than ever. The intellectual traditions of the neo-liberal era – open markets, deregulation, a smaller state – are no longer adequate to deal with these challenges; arguably, they may even have contributed to accelerating the crisis. Solutions cannot be found within the confines of a nation-state. Indeed, global cooperation for development has become existential for both the developed and developing world.

Western hegemony & China

I am not being romantic about this. Our ‘Apostles’ notwithstanding, there is much to critique about Western knowledge systems within which international development and its AID agencies are located, and the type of “development” it privileges. The global development project was never an altruistic project for promoting development and correcting historical wrongs. Since its inception in the post-World War II era, development has been a site in which great power competition has played out.

During the Cold War, it was an instrument for Western powers to create bulwarks against communism. As the Cold War receded, in the brief interregnum of the 1990s ‘end of history’ moment, the West, secure in its hegemony, effectively legitimised the fundamental inequalities within which development was structured. Even as the gap between developed and developing countries narrowed in this period—with both India and China beginning to experience high rates of economic growth—power in development agencies remained concentrated within a handful of high-income countries who shaped agendas and knowledge systems (including or perhaps especially when tackling the climate crisis).

The SDG agenda (and the Millennium Development Goals that preceded it) deepened the legitimacy of this power play. It created a mirage of comprehensive, universalistic goals that the world could sign up to without disturbing the underlying politics of power between the West and the developing world. Economic historian Adam Tooze makes the case provocatively. The SDGs, he argues, “were like an effort to craft a world organised around a spreadsheet of universal values rather than politics.”

In practice, this refusal to disrupt power asymmetries in development served to narrow the aid agenda and limit ambition at the cost of developing countries’ aspirations. Political scientist Yuen Yuen Ang, whose book How China Escaped the Poverty Trap challenges many orthodoxies in development, recently highlighted this asymmetry in a social media post.

Cash transfers have long been a favoured instrument in global development. A staggering 1.4 million papers have been published on cash transfers in the last 40 years. But Yuen asks: does this research tell us anything about the stated goal of development, i.e., large-scale societal transformation to improve the human condition? Cash transfers are in vogue in developing countries, India included, not because research proves their transformative powers, but because local politics and realities demand them (the research no doubt gives this legitimacy). As Ang reminds us, “no country has escaped poverty through cash transfers… it is about national growth and innovation…like in the gigantic case of China.”

And yet, this is where a phenomenal amount of talent, time and development resources have gone. Arguably, global development had already made itself irrelevant to the cause of enabling large-scale transformation long before Trump 2.0 pulled the plug.

The purpose of this critique is not to write development’s obituary but to call for a rebalancing of power in global development. Recognising and engaging with the power dynamics that shape development lays bare what is at stake for India.

Caught in unsustainable debt traps, disenchanted with the inequities of the current global regime, particularly visible in uneven vaccine distribution during the COVID-19 pandemic, developing countries around the world are in search of new partners. As Western aid retreats and the era of global cooperation dies, China, which already has a significant presence in Asia and Africa, is well primed to step into the breach and become a major development power for the world. This will likely be the greatest challenge to the current, increasingly fragile rule-based global order.

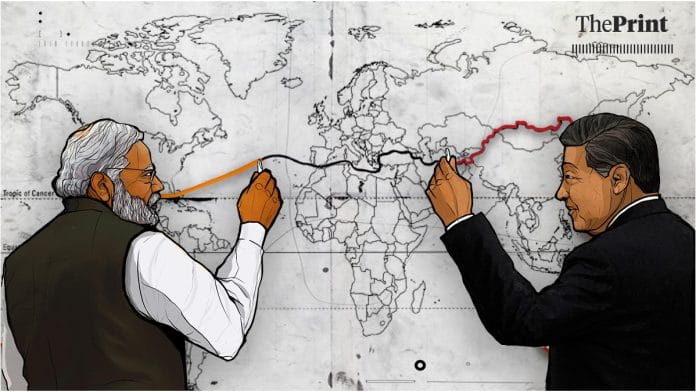

India’s power play on the global stage is threatened. Serving as a voice for the “global South” is part of India’s strategic toolkit to counter the geopolitical turbulence caused by Trump 2.0. Indeed, reports from the recent United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) suggest that nearly all the multilateral meetings held by India and its Minister of External Affairs, S Jaishankar, focused on global south issues and non-Western groupings. But India simply cannot compete with China when it comes to the scale and size of development financing.

Also read: What welfare scheme ghosts, fakes and deads teach us about EC voter list row

Bargaining for equity

There is, however, an alternative path. India’s democratic credentials and its historical willingness to exercise leadership with authority and moral clarity against global injustices have long been its source of influence among the developing countries. It still retains the global stature to take the discourse of development beyond instrumental power play—a game India cannot win—and instead build solidarities across the emerging economies and bargain for equity in the development agenda and preserve the fundamentals of the rules-based order.

This is not a fuzzy, feel-good appeal; it is realpolitik. India cannot compete with China in the development finance game, but its democracy offers a powerful alternative. India’s vibrant civil society and research community, itself a product of democracy, can be a real asset in this effort. India can lead the effort to build new knowledge systems and policy agendas relevant to the developing world. Experiments like social audits, tracking learning outcomes in primary schools, and efforts to develop pedagogical approaches to improve foundational literacy and numeracy led by social movements and NGOs have made their way to parts of South Asia and Africa. These successes can be leveraged as the building blocks of an alternative vision that India can offer the world.

But to take on this mantle and remain relevant, India will first have to fight its own demons and commit to allowing civil society and research, which forms the bedrock of development and innovation, to flourish. Given our own turn to narrow, petty nationalism, this seems like wishful thinking. But its long-term consequences on India’s global ambitions will be significant. Can we curb our basest instincts to preserve our own self-interest in this turbulent world?

Yamini Aiyar is a Visiting Senior Fellow at the Saxena Center and Watson Institute, Brown University, and the former President and Chief Executive of the Centre for Policy Research. Her X handle is @AiyarYamini. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)